The early 1960s was a period of decolonization in Africa. European countries had come to the realization that the burden of empire no longer warranted the cost and commitment to maintain them, except in the case where it was suspected that the Soviet Union was building a communist base. One of the countries which was trying to throw off the colonial yoke was the Congo and separate itself from its Belgian overlords. In 1960 it finally achieved independence and was led by a controversial figure, Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, a man who was ideologically an African nationalist and Pan-Africanist. However, soon after the Congo gained its freedom its army mutinied. The result was chaos and a movement by its Katanga province which was rich in mineral resources and led by Moise Tshombe to secede. What made the situation complex was that Lumumba was the country’s Prime Minister, and his president Joseph Kasavubu were often at loggerheads politically. Further, an army Colonel, Joseph Mobutu was placed in charge of the new Congolese army, the ANC who at times was loyal to Lumumba, and at times was in the pay of the CIA. The United Nations under the leadership of Dag Hammarskjold sought to try and end the chaos and bring a semblance of a parliamentary system to the Congo which in the end was beyond his reach.

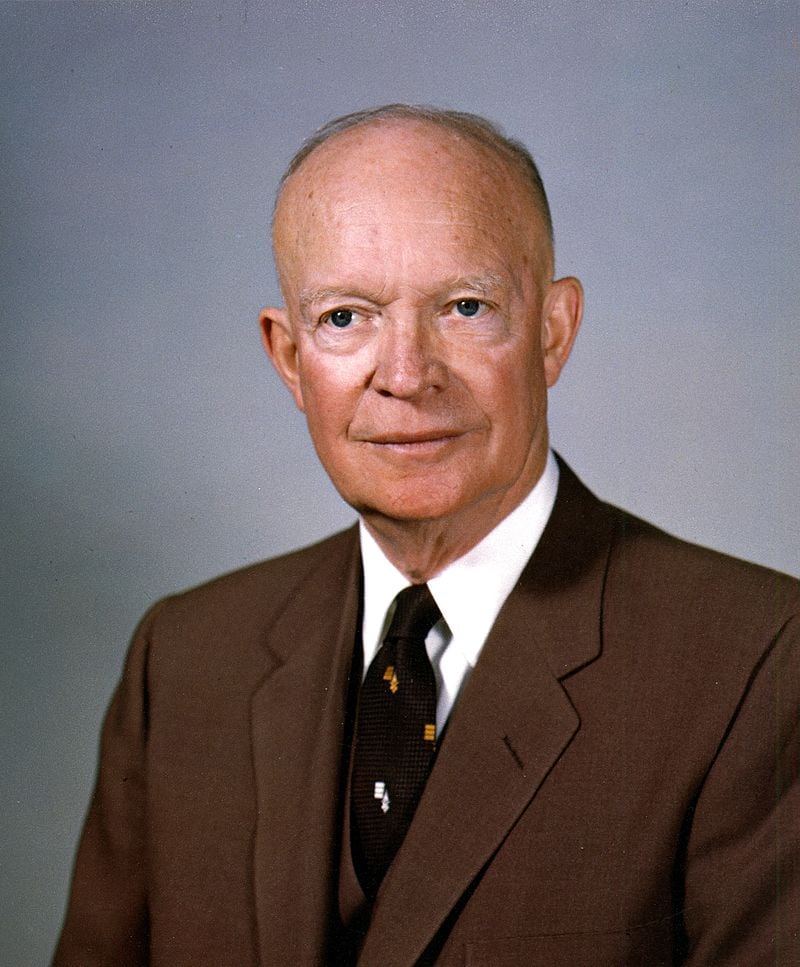

The early 1960s witnessed the height of the Cold War, Moscow would aid the new government and sought to spread its influence throughout Central Africa and gain a share of its mineral wealth. Washington’s response was predictable as it worked overtly and covertly to block the spread of Soviet influence and its communist ideology. The background that led up to Congolese independence and subsequent events is expertly told by Stuart A. Reid’s new book, THE LUMUMBA PLOT: THE SECRET HISTORY OF THE CIA AND A COLD WAR ASSASSINATION. The title of the book is a little misleading as the book does not focus much on the CIA in the Congo as it concentrates more on the concern of diplomats in the UN and a series of plots in Leopoldville. The international panic over the havoc in the Congo, Reid writes, helped to transform the Cold War “into a truly global struggle.” The monograph recounts numerous personalities and movements which exhibited shifting positions throughout the narrative. With Lumumba’s continuous machinations President Eisenhower’s inherent racism and anti-communism emerged along with his perceptions of Soviet actions which in the end led to the Congolese Prime Minister’s assassination by the CIA.

(CIA Station Chief Larry Devlin in he Congo, early 1960s)

If one examines the American approach to emerging nations and the Soviet Union during this period it is clear that if a leader labeled himself a nationalist or a neutralist, Washington labeled him a communist. The American foreign policy establishment was convinced for decades that nationalism and communism were one and the same and presented similar threats to American interests. A nationalist is someone who believes that their country should be ruled by their countrymen, not a government imposed from the outside. Historian, Blanche Wiesen Cook’s THE DECLASSIFIED EISENHOWER outlines the Eisenhower administration’s approach to nationalist leaders in the 1950s exploring the overthrow of Mohammed Mossadegh In Iran, Colonel Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala, a coup in Syria called off because of the Suez Crisis, attempts to remove Fidel Castro in Cuba, and of course events in the Congo. This approach continued under the Kennedy administration leading to errors resulting in disastrous approaches toward Vietnam, Cuba, and the Congo as these leaders of these countries believed they had a target on their backs. As a result, they would turn to the Soviet Union for aid which of course Premier Nikita Khrushchev was more than happy to provide.

In 1974 in the US Senate, the Church Committee learned about CIA coups, assassinations and other methods employed to influence foreign governments all in the name of American strategic interests as it did in dealing with Lumumba. The most important question that the author raises is who killed Lumumba? The choices are varied; Belgium which had run their colony with cruelty since the late 19th century; United Nations officials drawn into the Congo on a peacekeeping mission; the CIA fearing Lumumba was moving too close to the Communist bloc; or a young army officer, Joseph Mobutu who installed himself as leader. Reid’s interpretation of events relies on a multitude of sources, drawing from forgotten testimonies, interviews with participants, diaries, private letters, scholarly histories, official investigations, government archives, diplomatic cables, and recently declassified CIA files.

(CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb headed up the agency’s secret MK-ULTRA program, which was charged with developing a mind control drug that could be weaponized against enemies)

The book pays careful attention to the role of the United States, its motivations, unscrupulous methods, the damage that was inflicted on the Congo, and how US officials displayed racist contempt for the Congolese, particularly members of the Eisenhower administration. According to Reid, “the CIA and its station chief in the Congo, Larry Devlin, had a hand in nearly every major development leading up to Lumumba’s murder, from his fall from power to his forceful transfer into rebel-held territory on the day of his death.” Events in the region would reverberate far beyond the Congo as its short-lived failure of democracy resulted in poverty, dictatorship, and war for decades. Further it would claim the life of Dag Hammarskjold who was killed under mysterious circumstances during a peacemaking visit to the Congo months after Lumumba’s murder. The mission to the Congo was seen as a dangerous misadventure, and the UN never fully recovered from the damage to its reputation because of what occurred.

Reid details a brief history of Belgian colonization in the Congo. Ivory and rubber were a source of wealth, and their occupation was extremely cruel as depicted in Joseph Conrad’s HEART OF DARKNESS. For a more modern view of this period and Brussel’s heartlessness see Adam Hochschild’s KING LEOPOLD’S GHOST. Despite allowing the Congo’s independence, in large part due to outside pressure, Belgium would work behind the scenes to undermine Lumumba and his government until his death and after. The question is what did Lumumba believe? The governments sitting in Brussels and Washington were convinced that Lumumba was pro-communism and particularly vulnerable to Soviet influence. In fact, Reid argues that all the available evidence suggests he favored the United States over the Soviet Union. The problem was the prejudice against Africa which dismissed any possibility that an African man could successfully lead an African country. Ultimately, Lumumba’s fate is part of a larger story of unprecedented hope giving way to an unrelenting tragedy.

Mr. Reid tells an engrossing storyteller who guides us from events in Leopoldville and Stanleyville to negotiations in New York at the UN, Washington at the National Security Council, and the halls of the Belgian government in Brussels. The tragedy that unfolds is expertly told by the author as he introduces the most important characters in this historical episode. In the Congo, the most important obviously is Lumumba whose background did not lend itself to national leadership. He was a beer salesman, postal clerk who embezzled funds, and a bookworm who was self-educated. He would be elected Prime Minister and formed his only government on June 24, 1960, with formal independence arriving on June 30th. Other important characters include Joseph Kasavubu, Moise Tshombe, and Joseph Mobutu who all play major roles as Congolese political and ethnic particularism, in addition to Lumumba’s impulsive decision making and messianic belief in himself created even more problems.

For the United States, the American Ambassador to the Congo, Clare Timberlake convinced the UN to send troops to the Congo had a very low opinion of Lumumba as did CIA Station Chief Joseph Devlin who would be in charge of his assassination. President Eisenhower’s racial proclivities and looking at the post-colonial period through a European lens interfered with decision making as he ordered Lumumba’s death. He believed that Lumumba was “ignorant, very suspicious, shrewd, but immature in his ideas – the smallest scope of any of the African leaders.” CIA head, Allen W. Dulles called Lumumba “anti-western.” The UN plays a significant role led by Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold who tried to manipulate the situation that would support the United States, and he too thought that Lumumba was shrewd, but bordered on “craziness.” Ralph Bunche who made his reputation in 1948 negotiating with Arabs and Israelis did his best to bring the Congolese to some sort of agreement, but in the end failed. For Russia, Nikita Khruschev at first did not trust Lumumba, but soon realized there was an opportunity to spread Soviet influence and agreed to supply military aid to the Congolese army. Reid integrates many other characters as he tries to present conversations, decisions, and orders that greatly influenced the political situation.

(UN Secretary-General Gag Hammarsjkold)

The strength of the book lies in the author’s treatment of President Eisenhower’s and the CIA’s responsibility in the coup d’etat. The CIA persuaded Colonel Mobutu to orchestrate a coup on September 14. When the coup went nowhere the CIA turned to assassins who failed to carry out their mission. A scheme to inject poison in Lumumba’s toothpaste also went nowhere. In the end Patrice Lumumba at age thirty-five was murdered by Congolese rivals with Belgian assistance in early 1961, three days before John F. Kennedy who espoused anti-colonial rhetoric during his presidential campaign took office. Two years later Kennedy would welcome Mobutu Sese Seko who would rule the Congo, later called Zaire with an iron fist for thirty-two years to the White House.

Reid delves deeply into the personal relationships of the characters mentioned above. Attempts to get Tshombe to reverse his decision to secede from the Congo is of the utmost importance. Trying to get Lumumba and Kasavubu to cooperate with each other was difficult. Reid does an admirable job going behind the scenes as decisions are reached. The maneuvering among all parties is presented. Apart from internal Congolese intrigue the presentation of the US National Security Council as Eisenhower, Gordon Gray, the National Security advisor, Allen W. Dulles, and Secretary of State Christian Herter concluded before the end of Eisenhower’s presidential term that Lumumba was a threat to newly independent African states in addition to his own. In fact, at an August 8, 1960, National Security Council meeting , Eisenhower seemed to give an order to eliminate the Congolese Prime Minister.

(Moise Tshombe)

The role of Belgium is important particularly the June-August 1960 period as an intransigent Lumumba and an equally stubborn Belgium could not agree on the withdrawal of Belgian troops even after independence was announced. Belgium’s Foreign Minister, Pierre Wigney felt Lumumba was incompetent so how could Belgium reach a deal that could be trusted. Belgian obfuscation, misinformation, and cruelty stand out as it sought to leave the Congo on its own terms.

Another major player for the US was Sidney Gottlieb, who headlines a chapter entitled “Sid from Paris,” a scientist and the CIA’s master chemist who made his reputation experimenting with LSD as an expert in developing and deploying poison. He would meet with Devlin on September 19, 1960, and pass along the botulinum toxin which was designed to kill Lumumba but was never used.

Nicholas Niachos’ review in the New York Times, entitled “Did the C.I.A. Kill Patrice Lumumba?” on October 17, 2023 zeroes in on the role of the Eisenhower administration in the conflict arguing that Reid presented “new evidence found at the Eisenhower Presidential Library, Reid tracked down the only written record of an order at an August 1960 National Security Council meeting with the president, during which a State Department official wrote a “bold X” next to Lumumba’s name.“Having just become the first-ever U.S. president to order the assassination of a foreign leader,” Reid writes of Eisenhower, “he headed to the whites-only Burning Tree Club in Bethesda, Md., to play 18 holes of golf.”

Lumumba is re-elevated by the end of Reid’s book, mainly through the sea of indignities he suffered as a captive. Particularly disturbing is an episode from late 1960. His wife gave birth prematurely and his daughter’s coffin was lost when neither of her parents was allowed to accompany it to its burial.

In 1961, Eisenhower’s fantasies of the Congolese leader’s death — he once said he hoped that “Lumumba would fall into a river full of crocodiles” — were fulfilled. Lumumba was captured after an escape attempt and shipped to Katanga, where a secessionists’ firing squad, supported by ex-colonial Belgians, executed him. Reid shows how the C.I.A. station chief in Katanga rejoiced when he learned of Lumumba’s arrival (“If we had known he was coming we would have baked a snake”)but doesn’t ultimately prove that the C.I.A. killed him.

The C.I.A. has long denied blame for the murder of Lumumba, but I still wondered why Reid doesn’t explore a curious story that surfaced in 1978, in a book called “In Search of Enemies,” by John Stockwell. Stockwell, a C.I.A. officer turned whistle-blower, reported that an agency officer in Katanga had told him about “driving about town after curfew with Patrice Lumumba’s body in the trunk of his car, trying to decide what to do with it,”and that, in the lead-up to his death, Lumumba was beaten, “apparently by men who were loyal to men who had agency cryptonyms and received agency salaries.”

Still, Reid argues convincingly that by ordering the assassination of Lumumba, the Eisenhower administration crossed a moral line that set a new low in the Cold War. Sid’s poison was never used — Reid says Devlin buried it beside the Congo River after Lumumba was imprisoned — but it might as well have been. Devlin paid protesters to undermine the prime minister; made the first of a long series of bribes to Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, the coup leader and colonel who would become Congo’s strongman; and delayed reporting Lumumba’s final abduction to the C.I.A. On this last point, Reid is definitive: Devlin’s “lack of protest could only have been interpreted as a green light. This silence sealed Lumumba’s fate.”

(Patrice Lumumba)