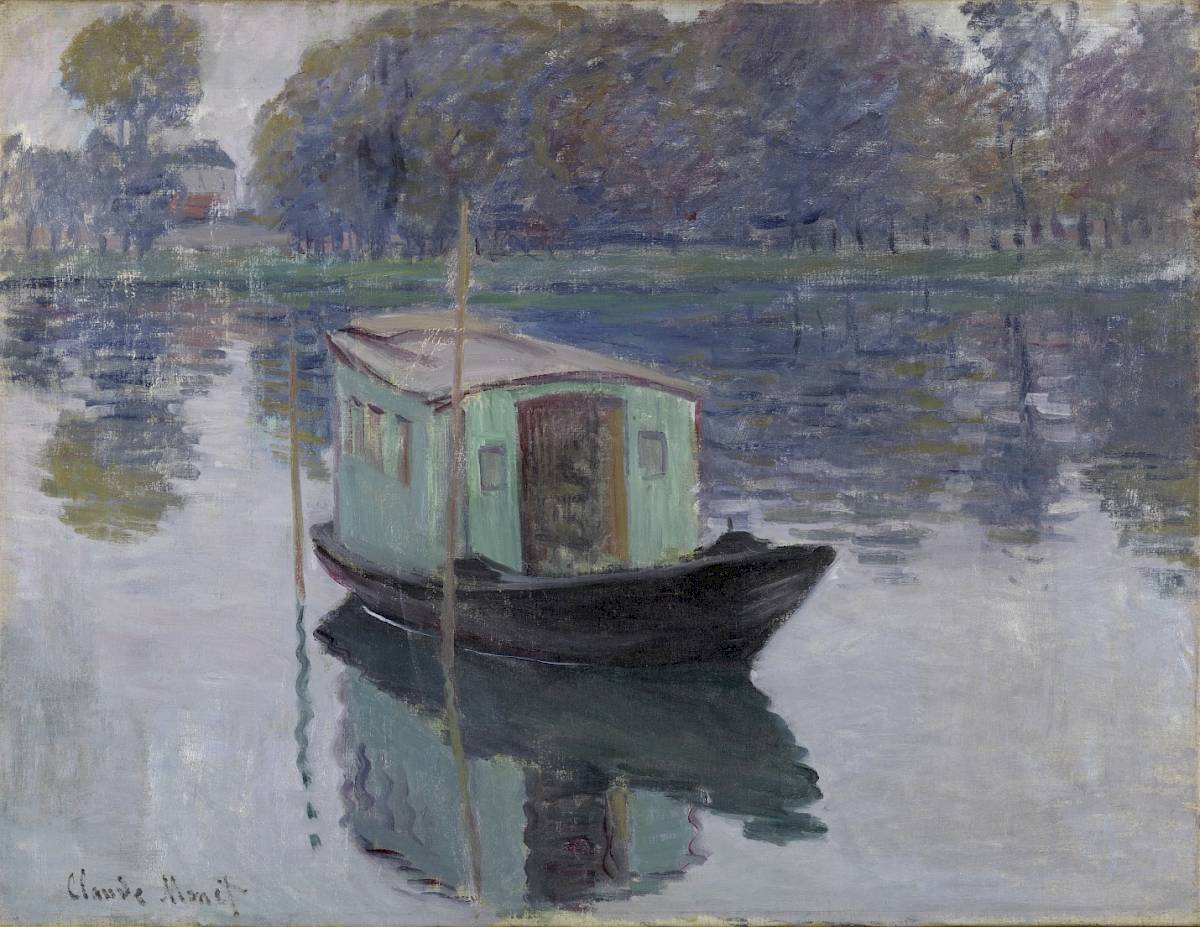

(Jorge Posada, Mariano Rivera, Derek Jeter, and Andy Pettitte, the “Core Four”)

Bill Pennington describes his new book as a story of “resurrection and rebirth.” It is the story of a once proud dynasty, the envy of sports franchises worldwide, so why use the terms just mentioned. Pennington’s book, CHUMPS TO CHAMPS: HOW THE WORST TEAM IN YANKEE HISTORY LED TO THE 90S DYNASTY begins with a bad omen. Yankee pitcher, Andy Hawkins, a career journeyman who was about to be released pitches a no-hitter against the Chicago White Sox. However, an asterisk is called for because he lost the game 4-0, an occurrence that had never occurred in baseball history. Such was the plight of the Yankees; attendance was down 35%, the farm system was bare, from 1989-1992 they had the worst record in team history, and the owner, the bombastic George Steinbrenner was banned from baseball. At a time when the gloried franchise has returned as a major force it is interesting to turn the clock back and see how it emerged from its doldrums to become the last dynasty of the 20th century.

(Gene Michael)

Pennington is on the top of his “game” throughout the narrative. A former beat writer who covered the Yankees, and sportswriter for the New York Times he had unparalleled access to the organizations executives as well as the players. He engaged in hundreds of interviews including the major characters including George Steinbrenner, Gene Michael, Buck Showalter, Don Mattingly, Mariano Rivera, Derek Jeter, Bernie Williams, Paul O’Neill, and Andy Pettitte. Pennington takes the reader on a year by year journey in Yankee history culminating in their resurgence winning the World Series in 1996 against the Atlanta Braves. During that journey the major issues that confronted the franchise are presented in detail concentrating on how the team fell into the abyss of the 1980s and early 90s.

(Buck Showalter on Seinfeld)

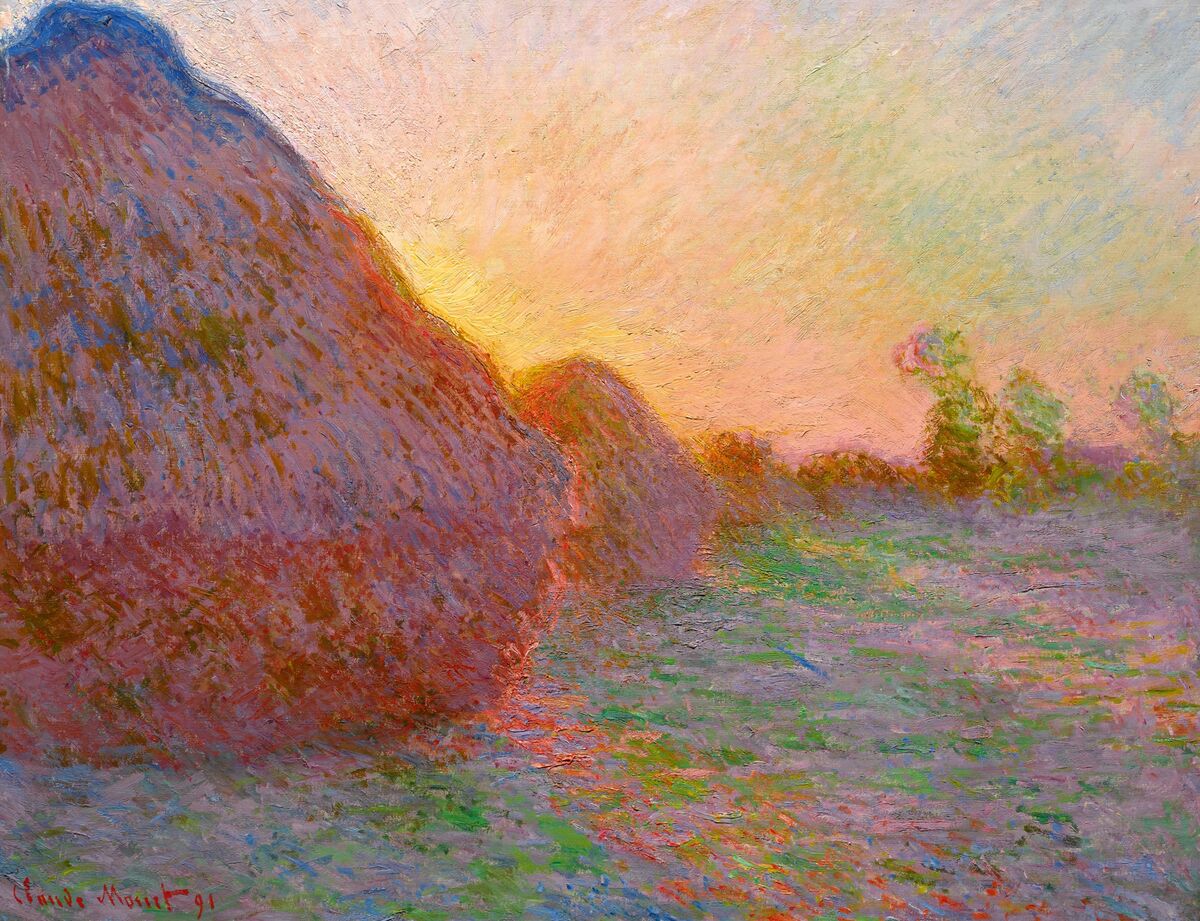

Pennington does a great job setting the scene of how far the resurgence traveled by exploring the depths of the 1980s. It seemed the Yankees did well in the 1980s, but in reality they were on a slow decline as its petulant owner, George Steinbrenner constantly interfered in “baseball” decisions; signing over the hill expensive free agents, trading away numerous prospects, and firing managers at the rate of one per year, in addition to rehiring and firing the same people multiple times. Pennington provides biographical sketches of the important individuals involved including Major League baseball officials, executives of the Yankee organization, and numerous players. In so doing the reader acquires insights from all points of view and gains an understanding as to what went wrong, and later what went right.

(George Stiernbrenner)

The key factor in the Yankee resurgence involves the arrogance and stupidity of George Steinbrenner. The Yankee owner who had previously been suspended from baseball because of illegal campaign contributions to Richard Nixon found himself in hot water once again in the early 90s. Steinbrenner had been at war with one of his high-priced free agents, David Winfield who he felt had lied about his contract and did not measure up to the standards that the Yankee owner expected. The disagreement involved donations to the Winfield Foundation, the paying of hush money to a convicted felon that Steinbrenner hired, and in the end Baseball Commissioner, Faye Vincent banned the Yankee owner for life, though it would be reduced to a two-year suspension after a year. During that time Steinbrenner was prohibited from being involved with major decisions involving the team. This allowed General Manager Gene Michael, Manager Buck Showalter, and the rest of the organization to set the Yankees on a new path.

(Paul O’Neill)

The change in strategy including the early use of analytics, keeping their own prospects as the farm system began to blossom, creating a new culture in the clubhouse by acquiring certain types of players, and developing a consistent organizational philosophy that would be implemented throughout their minor league system up through the major league level. As Brian Cashman, then Assistant General Manager has pointed out, the success the Yankees would achieve in 1993 and 1994 while Steinbrenner was away from the team allowed for the implementation of the new approach. Once Steinbrenner’s suspension ended, he came back and allowed his baseball people to make decisions rather than himself. The key point is that if Steinbrenner had not been exiled the success of the late 1990s would not have occurred.

(Bernie Williams)

It is one thing to change philosophies it is another to have the management and players to implement it. Pennington is correct in arguing that Michael knew how to deflect Steinbrenner’s urges, as Cashman would also do once he took over as General Manager. Further, Pennington describes how effective the scouting department was uncovering players like Bernie Williams, and the core four of Mariano Rivera, Derek Jeter, Jorge Posada, and Andy Pettitte. These players were supplemented by many others, but a climate of winning and accountability was created, that proved successful.

(David Cone)

Perhaps the best chapters in the book deal with the relationship between Michael and Showalter and how they built the Yankees and dealt with Steinbrenner. As in all relationships there is a watershed moment that alters the course of history. Pennington does a superb job describing the events of 1994 and how the Yankees felt robbed by the baseball strike when they were on the cusp of winning a championship, and the loss to Seattle in the 1995 playoffs. At the conclusion of that series Michael and Showalter did not return as General Manager and Manager for 1996 and Don Mattingly retired never to appear in a World Series. Later, Steinbrenner admitted that not bringing Showalter back was his greatest mistake, and on a positive note it taught him to leave the team to his baseball people for the remainder of his life as he morphed into the realm of a benevolent patriarch. It is ironic that in 2001, Showalter would be attending game seven of the World Series as an ESPN analyst where the two teams he helped build, the New York Yankees and Arizona Diamondbacks would play for the championship.

As a Yankee fan since the 1950s I have witnessed a great deal of Pennington’s narrative from my own observations and reading newspapers on a daily basis. The author hits all the major points, develops the most important personalities, and reaches the correct conclusions in explaining the remaking of the New York Yankees from a declining power to a constant force in major league baseball over the last three decades. If you are a baseball fan you will love this book. If you are a general reader it presents a story of redemption and change that has benefited millions of people and shows if you take a thoughtful approach to an endeavor and leave out impatience and bombast you can be very successful.