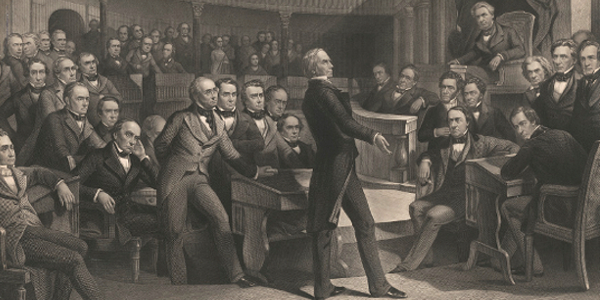

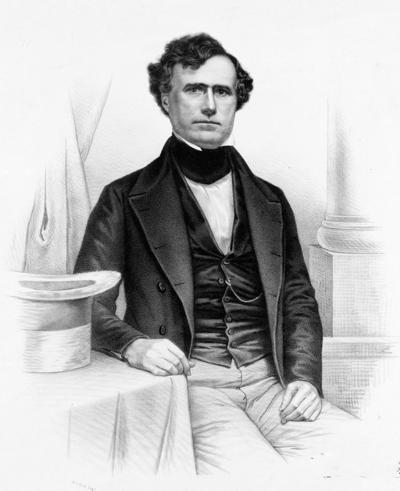

In many ways Jon Meacham is the conscience of America. The Vanderbilt historian and author has a very optimistic view of the American people and his appearances on MSNBC and other programs is usually upbeat when it comes to the future of the United States. This viewpoint is readily apparent in a number of his books, including THE SOUL OF AMERICA: THE BATTLE FOR OUR BETTER ANGELS where he discusses turning points in American history and how we have overcome numerous issues including partisanship. Meacham is a prolific author whose books include FRANKLIN AND WINSTON: AN INTIMATE PORTRAIT OF AN EPIC FRIENDSHIP, AMERICAN GOSPEL: GOD, THE FOUNDING FATHERS AND THE MAKING OF THE NATION, AMERICAN LION: ANDREW JACKSON IN THE WHITE HOUSE, HIS TRUTH IS MARCHING ON: JOHN LEWIS AND THE POWER OF HOPE, and DESTINY AND POWER: THE AMERICAN ODDESSY OF GEORGE HERBERT WALKER BUSH. All books are well written with a degree of empathy for his subjects which is the case with his latest effort, AND THERE WAS LIGHT: ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND AMERICA’S STRUGGLE which tells the story of our 16th president from his birth on the Kentucky frontier to his leadership during the Civil War through his assassination. For Meacham, Lincoln’s life illustrates the ways and means of politics in a democracy, the roots and durability of racism, and the capacity of conscience to shape events.

Meacham’s Lincoln is a humane and empathetic individual who must overcome personal tragedy and his own demons. The death of two children, a depressive personality, and a spouse who caused trouble repeatedly must be dealt with as he tries to maintain the union and reunify his country. Lincoln did not shy away from complex decisions whether dealing with politics, military personnel, or wartime strategy. He was a firm believer in Jeffersonian equality and the constitution. He was not averse to making compromises to maintain the union and a democratic form of government. The idea that the federal government could not end slavery in states where it existed but could prevent its expansion into new territories was deeply ingrained in him. According to poet and editor James Russell Lowell who wrote in 1864, for Lincoln it was more convenient to say the least, to have a country left without a constitution, than a constitution without a country.”

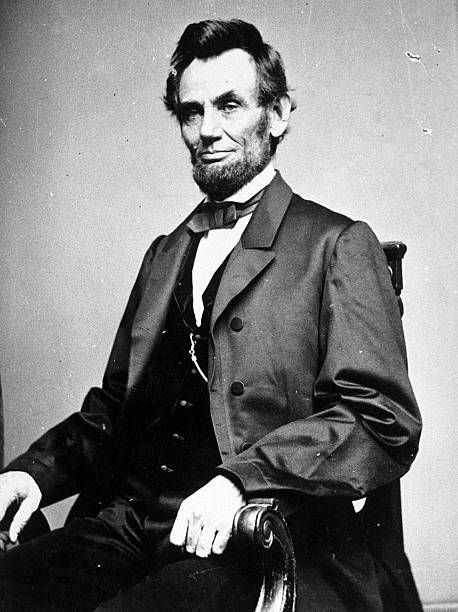

(Lincoln at the battle of Antietam)

Meacham’s account of Lincoln’s treatment of slavery is heavily laden with theological arguments and experiences which Lincoln argued was his own enslavement by his overbearing father who forced him to labor and forgo education, to the exposure to reverends preaching against slavery during his boyhood. Meacham develops anti and pro-slavery ideology throughout the narrative and concludes that Lincoln did not believe in racial equality, favored the colonization of slaves to areas outside the United States, but overall, he could not tolerate individuals being owned by another and having to labor for someone not of his choosing.

The narrative carefully recounts Lincoln’s evolution concerning the slave issue relying on his religious and political development. Lincoln was a man of compromise in all areas, but not concerning the maintenance of the union. Meacham reviews the most important debates, events, and movements of the period and offers a dissection of Lincoln’s thought processes and how he finally reached the conclusion in 1862 that after trying everything to appease the south and keep the states as one to announce the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

Lincoln only served one term in Congress, but it was an important education. He learned a great deal about slavery coming into contact with southern members of the House of Representatives, opposing racist legislation, and the need of compromise, not conquest in order to make meaningful change. Lincoln repeatedly turned to the “Founders” for inspiration and if one examines his speeches it is a combination of religious belief and political pragmatism. As Lincoln stated in 1861, “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.”

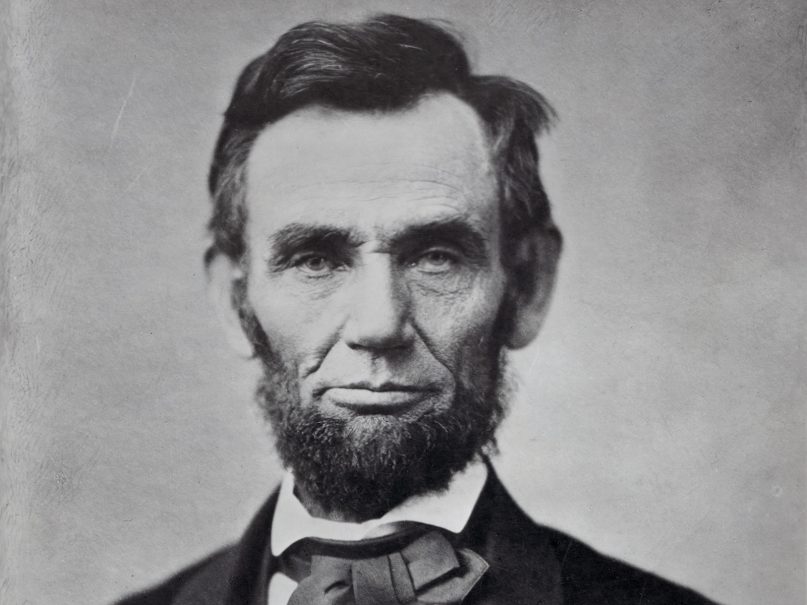

(Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee)

According to historian Richard Carwardine, “the fatalist and activist were thus infused in Lincoln.” He was a dichotomy. He articulated his moral commitment against slavery and his willingness to leave a white dominated society intact. For him racial prejudice among whites was at such a level that the practical course was to acknowledge and accommodate it.

There are countless interesting aspects of Lincoln’s life that Meacham introduces. One of the most surprising is his obsession concerning his own birth – was he illegitimate? Did policy decisions emanate from his own inferiority about his own birth that summoned temporal and divine help, as he tried to put the national family back together when his own family origin was in doubt?

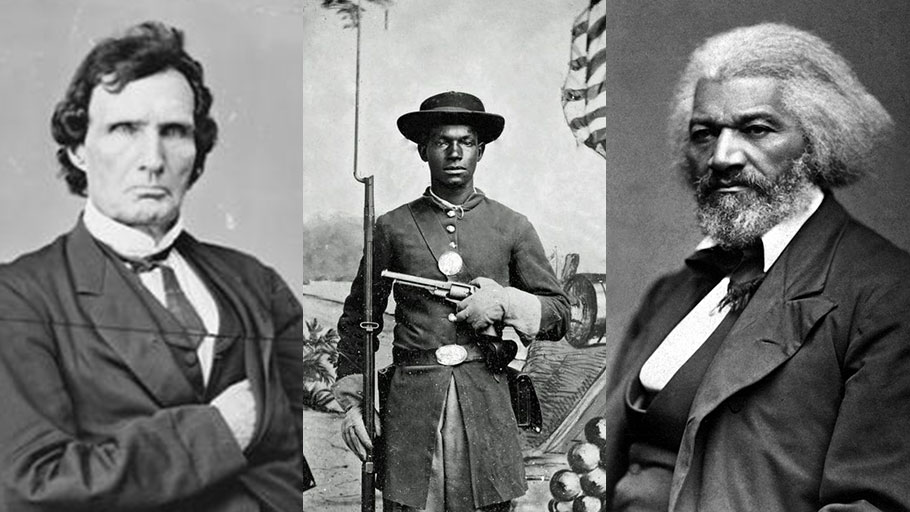

Meacham does an excellent job reviewing events leading to the Civil War, the course of the war, and the ultimate victory of the north which cost Lincoln his life. The author concludes that in most aspects of his narrative race is the central cause of the conflict as even if he would free the slaves northern racists were on par with those in the south – the only difference was they did not want to enslave them, but they could not accept that they were equal.

AND THERE WAS LIGHT is not a traditional biography of our 16th president. It is more a conversation with an eminent historian who examines the intellectual development of his subject while at the same time placing him in the context of the world he lived in and the difficult choices that he made. Meacham offers an account that is worldly and spiritual, and carefully tailored to suit our conflict-ridden times. Meacham alludes to the present with examples from the past. A case in point is Vice President John Breckinridge’s courageous decision to carry out the electoral college faithfully in February 1861 as Mike Pence did in 2021. Further Lincoln promised to accept the results of the 1864 election, even if he lost, Donald Trump and Kari Lake are you listening? Lastly, Lincoln’s support for absentee voting for soldiers, unlike Trump’s call to outlaw the process. Lincoln faced a White supremacists national minority chafing against Jeffersonian ideals which Lincoln was committed to. With January 6th and further threats of violence Meacham tries to use Lincoln as an example of leadership in somewhat similar times.

The book is thoroughly researched and highly readable written by a craftsman of the English language. The book as are his other works is relevant for today as Meacham writes, “ A president who led a divided country in which an implacable minority gave no quarter in a clash over power, race, identity, money, and faith has much to teach us in a twenty-first century moment of polarization, passionate disagreement, and differing understandings of reality. For while Lincoln cannot be wrenched from the context of his particular times, his story illuminates the ways and means of politics, the marshaling of power in a democracy, the durability of racism, and the capacity of conscience to help shape events.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121121013133tad-lincoln-turkey-pardoning.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/lincoln-tripline-631.jpg)

/Lincoln-Gettysburg-painting-2826-3x2gty-58b999143df78c353cfd0b25.jpg)