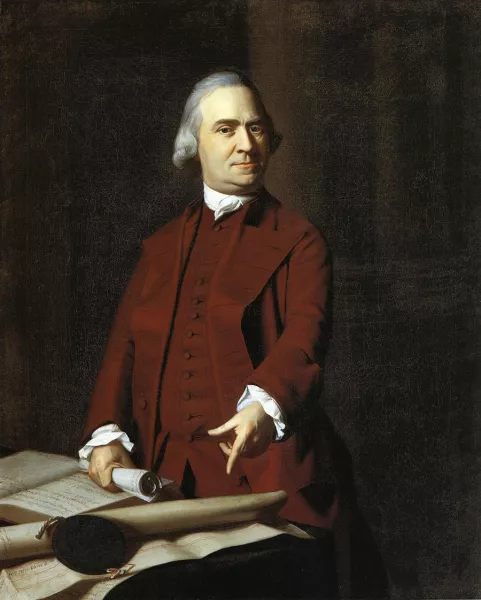

(Samuel Adams)

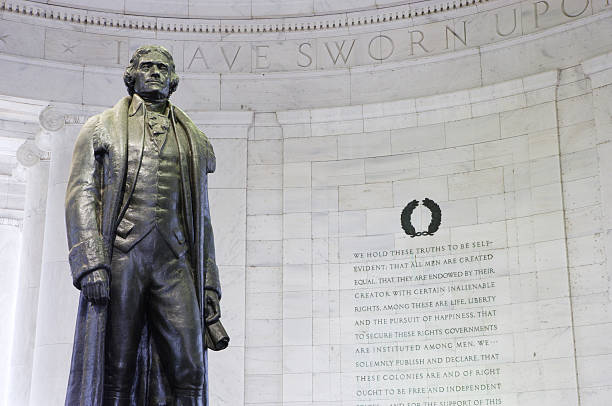

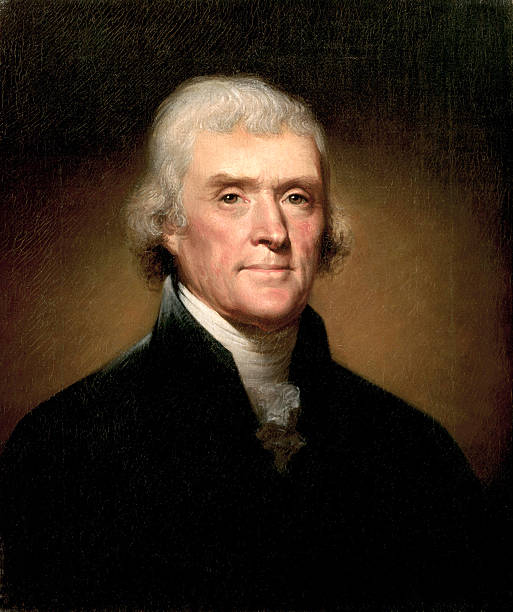

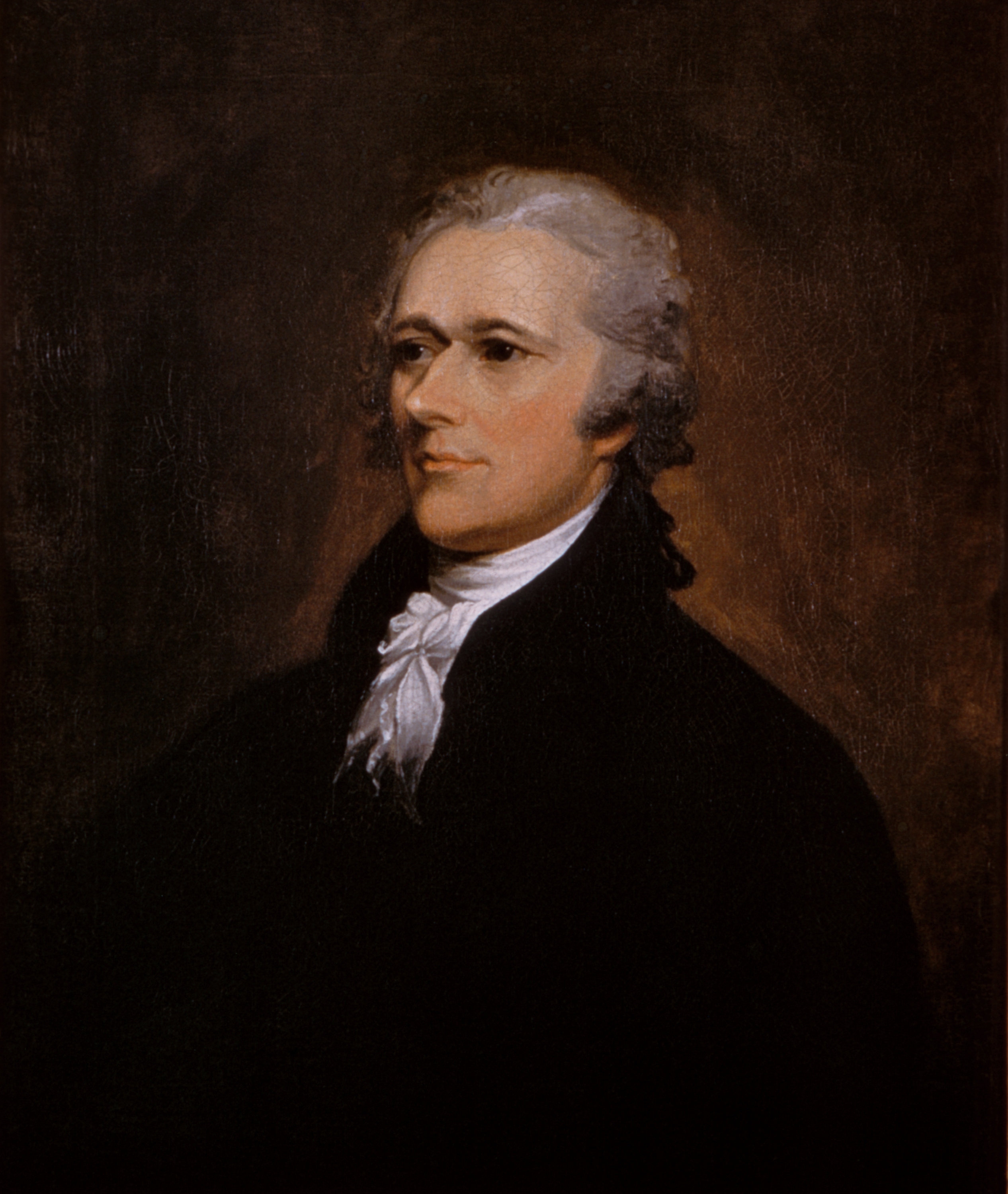

What criteria should be used to determine if a person can be labeled a “founding father?” We all know that John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, George Washington and a host of others qualify, however each has their own foibles and when examined they may detract from their reputations. Do other members of the American Revolutionary generation qualify? If so, whom? In Stacy Schiff’s latest work, THE REVOLUTIONARY SAMUEL ADAMS the author makes the case for the cousin of John Adams to join this elite company. Schiff, a Pulitzer Prize winner is also the author of THE WITCHES OF SALEM, 1692, A GREAT IMPROVISATION: FRANKLIN, FRANCE, AND THE BIRTH OF AMERICA, and biographies of Cleopatra, Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov, and Saint-Exupery. Schiff explores the birth of the American Revolution in Boston and the artful and elusive instigator and master of misinformation whose contributions made it all happen – Samuel Adams.

Adam Gopnik in his review of Schiff’s work in The New Yorker, October 31, 2022, characterizes Adams’ role in the revolution as almost invisible, “but his fingerprints are everywhere. He shaped every significant episode in the New England run up to war. Yet how he did it, or with what confederates, or even with what purpose – did he believe in American independence from the start, or was it forced on him by the wave of events, as it was on others? – is muddied by an absence of diaries or letters or even many firsthand accounts.” It is a credit to Schiff that lacking documentary evidence she constructs her book “from a pleasant tapestry of incident and inference. She has a fine eye for the significant detail and knows how to compose that lovely thing the comic-comprehensive catalogue.”

After reading Schiff’s narrative it is clear that Samuel Adams should be labeled the “instigator-in-chief” of the American Revolution. Adams was an opportunist, a purveyor of half-truths, but in the end truly idealistic. Schiff explores Adams’ role in the American political theater of the day as he “employed unreliable rumormongering, slanted news writing, misleading symbolism, even viral meme-sharing” – all of which was evident from the outset of his revolutionary role. He inaugurated the American tradition of show-business politics but was also a realist realizing that his goals could not be achieved without colonial unity.

(British Governor Thomas Hutchinson)

Schiff’s focus centers on a few major events and significant personalities. The author does an exceptional job in these areas as she dissects the Land Bank Committee, the Stamp Act, the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party, and the growth of the Committees of Correspondence, and what transpired at Lexington and Concord. As far as individuals, she sets Adams against Governor Thomas Hutchinson and General Thomas Gage who also served as Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Other influential figures include Dr. James Warren, John Dickinson, Thomas Paine, James Otis, John Adams, Thomas Cushing, John Hancock, Paul Revere, and Benjamin Franklin.

Schiff’s approach is chronological as she follows Adams’ actions from 1751 through the onset of revolution. It is not a traditional biography as Schiff zeroes in on Adams’ “words” and his ability to rile the British and bring about an inclusive colonial network that pushed against Britain’s attempt to control the colonies and use them as a “monetary source” in order to pay for its large debt dating to the French and Indian War.

Adams’ radicalization stems from the 1751 Land Bank Committee whose currency policies and trade imbalance increased the debts of many Boston residents including Samuel Adams. Adams would develop the Boston Gazette in order to disseminate his views as a result, and ironically he was appointed a tax collector in 1758. In her discussion Schiff provides an excellent description of pre-revolutionary Boston and the Massachusetts Bay Colony in general.

Up until 1764 Adams personal situation consisted of debt, loss of family, the collapse of his malt business, fighting with creditors, etc. But 1764 would become a watershed year in his career as an agitator for less British control of the colonies because of the imposition of the Sugar Act as London sought increased revenues from colonies undergoing tremendous economic growth. That summer Schiff points out that Adams marriage to Elizabeth Wells was as significant as British actions as her ambitions and strengths mirrored those of her husband.

Schiff’s insightful commentary is on full display with the issuance of the Stamp Act in 1765 as Adams argued that London’s actions actually benefitted the colonies as it awoke in them their desire for the rights and privileges of Englishmen and helped unite the colonies. Further, it would spawn the creation of the Sons of Liberty.

Throughout, Schiff develops the back and forth between Adams and Hutchinson. The British governor believed that Adams was the devil and was responsible for everything that went wrong during his reign from the destruction of his house to the dumping of tea in Boston Harbor. The author provides the letters, articles, and speeches of each highlighting her extensive research. Schiff also does admirable job delving into personalities, viewpoints, and actions of members of the Massachusetts Legislature and their overall relationship with the crown. Governor Francis Bernard, who preceded Hutchinson in office, Otis, Adams, Cushing, Hancock, and the role of others are all stressed.

(British General and Governor Thomas Gage)

Schiff concentrates on Boston and all the major events that took place in the city, but also how these events affected Philadelphia and New York including their response. Adams’ most important creation may have been the Committees of Correspondence which can be considered an 18th century “twitter” which allowed the colonies to communicate with each other and be kept up to date with the latest news and movements or as one reviewer described as “a patriot espionage network.” Adam’s action helped unify the colonies, with major help from London whose imposition of the Townshend Acts which imposed new taxes on paper, paint, nails, and tea in 1767, the Quartering Act which stated colonists had to house British troops, British troops firing on Boston citizens in 1770, the Port Act, and blockading Boston after the Tea Party in 1773 made Adam’s task that much easier.

Periodically, Schiff shifts her focus to Adam’s writing style and strategy. Words came easily to Adams, who could “turn a small grievance into an unpardonable insult before others had arrived at the end of a sentence.” It was the golden age of the printed word with six newspapers in Boston alone. One of Adam’s most effective tools was the use of “pseudonyms” be it Vindex, Candius, A Chatterer, A Son of Liberty, over thirty in all which was quite successful and allowed Adams to seem as if he were everywhere. Other tools in the toolbox included lies, facts, imagery, comments by royalists, and of course his creativity, i.e.; exploiting vocabulary by applying words such as inalienable and unconstitutional.

Schiff’s research provides a roadmap into Adam’s thoughts. She dissects his arguments and admires his ability to create havoc and develop support for his cause throughout the colonies against London. In each instance she explains the actions and opinions of major events as they develop and how the important personalities coped with them. One of Schiff’s strengths is her ability to discuss the role of each player in any situation. A case in point is whether the Boston Tea Party would have occurred without his leadership.

(John Hancock)

It is clear from Schiff’s narrative that Samuel Adams was the prime mover in prodding the colonists from loyalty to rebelliousness against England in less than a decade. The text deals very little with Adam’s pre-revolutionary career and post-revolutionary life zeroing in on a 15 year period from 1764 on. As historian Amy Greenburg writes in her October 22, 2022, New York Times Review, arguing that lessening Adam’s role in the revolution was a mistake and “Stacy Schiff redresses this oversight by celebrating the man who “wired a continent for rebellion.” There is a lot to admire about this rabble-rouser. He was utterly incorruptible; colonial authorities tried to buy him off with public office (“the time-honored method”), but Adams could be neither bribed nor intimidated. He cared nothing for personal gain, and, in his own words, gloried “in being what the world calls a poor man.” He was deeply idealistic, had great personal equanimity and was a gifted orator. He promoted public education for women long before it was fashionable. He was a tender father to his two children and, although his financial mismanagement forced his wife into manual labor while he was at the Second Continental Congress, he was also a loving husband. Readers are reminded more than once that Adams abhorred slavery, and when offered the gift of an enslaved woman, he insisted that she be freed before joining his household. Schiff paints a vivid portrait of a demagogue who was also a decorous man of ideals, acknowledging Adams’s innovative, extralegal activities as well as his personal virtues.” After digesting Schiff’s arguments, It is clear that Samuel Adams deserves to be labeled as part of that august group of “founders.”

(Samuel Adams)

![[Washington and Jefferson] Look on This Picture, and On This](https://www.pafa.org/sites/default/files/artworkpics/1876_9_11_l.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ee/68/ee680751-afb7-45a9-864e-dc8cc2747ca4/benjamin_rush_stipple_engraving_by_w_s_leney_1814_after_wellcome_v0005143er_edit.jpg)