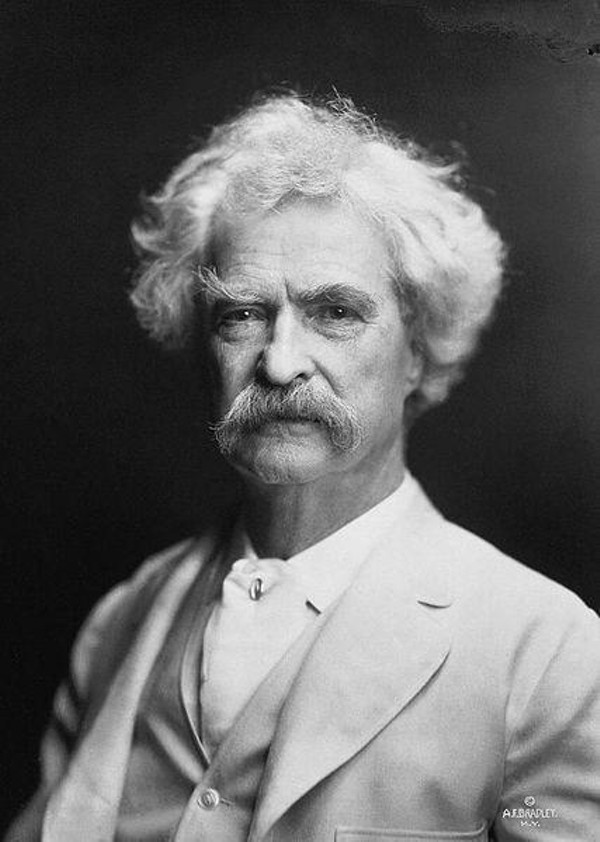

(Mark Twain)

Stephen Kinzer is a prolific writer and historian among whose books include ALL THE SHAH’S MEN an excellent study that explains the 1979 Iranian Islamic Revolution and the origins of our conflict with that country. Other books; THE BROTHERS, a fascinating dual biography of Allen W. and John Foster Dulles, men who significantly impacted American intelligence gathering and foreign policy throughout the 1950s; and OVERTHROW, a study that explains how Washington conducted a series of coups from Hawaii to Iraq to install governments that it could control. If there is a theme to Kinzer’s books it is that the United States has conducted a series of forays into foreign countries that reek of imperialism and have not turned out well. His latest effort, THE TRUE FLAG: THEODORE ROOSEVELT, MARK TWAIN, AND THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN EMPIRE follows the same theme and tries to bring about an understanding of why and how the United States began its journey towards empire.

(President Theodore Roosevelt)

From the outset Kinzer describes a conflicted American approach toward foreign policy. It appears that Americans cannot make up their minds on which course to follow: Should we pursue imperialism or isolationism? Do we want to guide the world or let every nation guide itself? This inability to decide has played itself out from the end of the nineteenth century until today as we try and figure out what avenue to take following the disastrous invasion of Iraq in 2003 and its ramifications. Kinzer argues that “for generations every debate over foreign intervention has been repetition,” however, “all are pale shadows of the first one” that began in 1898 is developed in THE TRUE FLAG. Kinzer zeroes in on one of the most far reaching debates in American history that was fostered by the Spanish American War, not the Second World War as most believe; should the United States intervene in foreign lands, a debate that is ever prescient today.

(Henry Cabot Lodge)

Following the results of the war against Spain, the United States found itself in possession of Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and was about to annex the Hawaiian islands, leading to a fever of empire among many Americans in and out of government. Kinzer traces the political machinations that resulted in the new American Empire. He also takes the reader behind the scenes that resulted in decisions that led to what President McKinley termed “benevolent assimilation” for the Philippines, or a more accurate description, a race war to subdue Filipino guerillas led by Emilio Aguinaldo. Kinzer has full command of the history of the period politically, militarily, and economically. He has extensive knowledge of the secondary and primary materials, and writes with a clear and snappy prose that maintains reader interest.

What separates Kinzer’s narrative and analysis from other studies dealing with this topic is his focus on the debate over American expansionism that created the Anti-Imperialist League to offset the arguments of the imperialists in and out of Congress. He provides a blend of both arguments integrating a great many heated speeches and articles that the protagonists engaged in and produced, even describing a fist fight in the Senate between the senators from South Carolina over a vote that ratified the Treaty of Paris. Kinzer focuses on a number of important historical characters that include; Theodore Roosevelt who used the Spanish-American War as a vehicle to advance politically; Henry Cabot Lodge, a strong believer in the “large policy” of imperialism as the Senator from Massachusetts; William Randolph Hearst whose newspaper helped incite the war, and would later turn against imperialism as he sought a political career; President William McKinley who supposedly received divine guidance to pursue his expansionist agenda; Mark Twain, writer and satirist who initially favored expansion, then became the “eviscerating bard” against empire; William Jennings Bryan, the “free silver” commoner from the Midwest who was defeated three times for the presidency; Andrew Carnegie, the richest man in America, but opposition to imperialism for him was almost a religious cause; and Carl Schurz, a German immigrant who fought in the Civil War and served as Secretary of the Interior among many important positions during his career.

(Andrew Carnegie)

Perhaps the strongest aspect of Kinzer’s narrative discusses the two opportunities that Bryan had to stem the imperialist tide. Bryan was an avid opponent of expansion from the moral perspective, but he would cave to political ambition on two occasions. The first, during the debate in Congress over the Treaty of Paris which would cap America’s territorial aggrandizement from the war. At the last minute Bryan decided to support the treaty and America’s possession of the Philippines. Second, as the Democratic candidate for president in 1900 he refused to leave out his “free silver” plank from the convention platform and concentrate on the anti-imperialist message. By not doing so he scared away eastern business opponents of expansion and a number of allies in the Democratic Party. The result was the passage of the treaty and the reelection of McKinley.

(President William McKinley)

Another fascinating aspect of the book is Kinzer’s treatment of Mark Twain. Kinzer offers a detailed discussion of Twain’s arrival from Europe on October 15, 1900 in the midst of the imperialism debate and his transition to his anti-imperialism stance. A number of Twain’s writings and comments are presented and analyzed and compared with those of Theodore Roosevelt, whose ascendancy to the presidency after McKinley is assassinated, effectively kills the Anti-Imperialism League. Twain’s writings detail his disgust for events in the Philippines and the disaster that ensued. Twain is presented along with other famous writers and poets whose anger at expansion and its results knew no bounds. However, the work of Finley Peter Dunne and his Mr. Dooley character, written with an Irish workman’s accent is probably more important in that it reached the illiterate masses, while others appealed to the social and political elite.

Kinzer’s narrative packs a great deal into 250 pages and it is a fast read. However, do not evaluate this book by its length because it presents an excellent synthesis and analysis of the important events, personalities, and policies of the 1898-1902 period as America debated if it should become an empire, the type of debate that was missing in the United States as we contemplated invading Iraq in 2003. A war that we are still paying for today. In the end many of the predictions set forth by the anti-imperialists have come to pass, just examine American foreign policy since the end of World War II. We as Americans must answer the question: “Does intervention in other countries serve our national interest and constitute global stability, or does it undermine both?” (229)

(Mark Twain)

.jpg)