(Chamberlain and Hitler at Munich, September, 1938)

For those who are familiar with the works of Robert Harris they are aware of how the author develops fictional characters that are integrated into important historical events. He has the knack of developing individuals like Xavier March in FATHERLAND, George Piquart in AN OFFICER AND A SPY, Tom Jericho in ENIGMA, and Fluke Kelso in ARCHANGEL in presenting accurate scenarios that make one feel that these characters are real. Harris is a master of historical fiction, but his new characters Hugh Legat and Paul von Hartmann in his latest novel, MUNICH are somewhat lacking in reaching the standard for fictional historical characters when compared to previous novels.

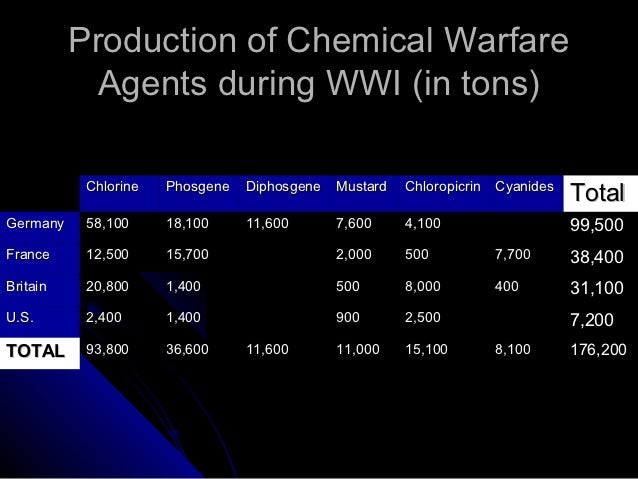

Whether one is familiar with J.W. Wheeler-Bennett’s MUNICH: PRELUDE TO TRAGEDY, David Faber’s MUNICH: 1938, APPEASEMENT AND WORLD WAR II, Giles MacDonogh’s 1938: HITLER’S GAMBLE, and Telford Taylor’s MUNICH: THE PRICE OF PEACE the best historical monographs on the Munich Conference, they will realize as they read Harris’ new novel how immersed the author is in his subject matter, and how accurate is his command of detail. From the get go British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain is an appeaser questioning why should England go to war for the Sudetenland and repeat the carnage of World War I. Adolph Hitler is presented as an expansionist bent on Lebensraum (living space in the east) and achieving self-determination for all Germans, Benito Mussolini is a puffed up narcissist who resents being in the Fuhrer’s shadow, and Edouard Daladier is tied to Chamberlain’s coat tails and takes no initiative.

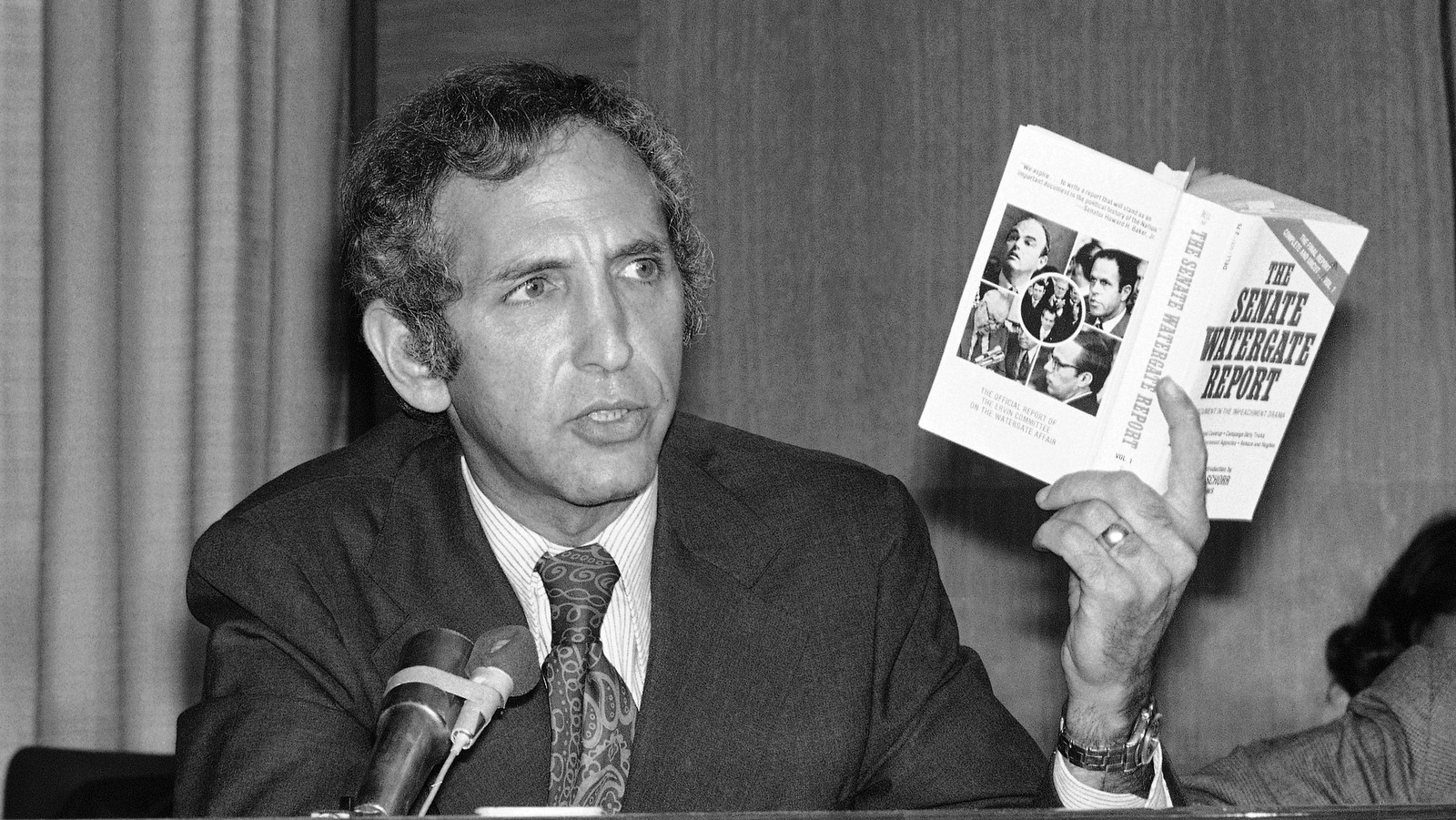

The novel’s plot rests on the assumption that Legat, a British Foreign Office functionary, and von Hartmann, a German bureaucrat will be able to change European history by their machinations during the four days of the Munich Conference. The hope is that the German resistance can convince Chamberlain to stand up to Hitler which would allow the German army to support a coup against the Fuhrer. The concept of the German army supporting a coup is debatable, but it is a feasible plot. The problem with this approach is that the heightened tension that Harris tries to create does not really materialize. I feel this way because I have read a good deal of the books on the topic that are recommended at the end of the book, and the fact that the results of Munich are well known. Further the concept of “appeasement” and the term Munich are dirty words for American politicians also make the novel’s plot somewhat of a stretch to accept.

(Mussolini, Hitler, Daladier, and Chamberlain at Munich)

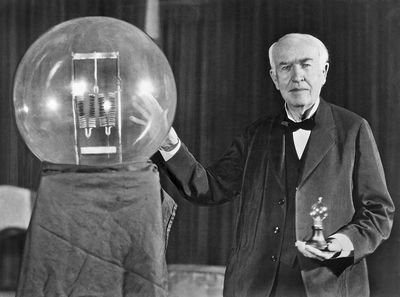

To Harris’ credit he has a marvelous talent in providing intricate details as his characters communicate. Be it a description of a Remington typewriter, the way an SS uniform is contoured, or how members of the British delegation appeared in rumpled suits his eye for the minute is amazing. In fact one of the more interesting aspects of Harris’ approach is his ability to use the body language and facial expressions of his characters as a means of providing a window into their thinking. The author also has the knack of introducing important primary materials integrated into his story. Chamberlain’s speech to Parliament as he reports that Hitler has invited the four major powers to Munich to settle the Sudeten problem is a case in point. Another example is the introduction of the November, 1937 Hossbach Memorandum that outlined Hitler’s goal of Lebensraum (living space) in the east, and his plans for future expansion through war. These are just two examples of how throughout the novel Harris relies as much as possible on primary sources.

(Chamberlain speaking at an airport in London upon returning from Munich promising “peace in our time”)

Perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of Harris’ presentation is his portrayal of Chamberlain’s raison d’tre in dealing with Hitler. He does not see Chamberlain as an appeaser but a skillful negotiator who stalls for time as he gets Hitler to agree to a settlement with the Czechs over the Sudetenland, and also accepts the concept of a stronger Anglo-German approach to peace. In fact in a recent interview (January 19, 2018) on NPR’s “Morning Edition” Harris argued that Chamberlain was the victor at Munich because the war was postponed for a year allowing the English to gain the support of the Dominions and the Empire as a whole, and provided time for the British military production to begin to catch up with Germany. Further he argues Hitler never wanted to go to Munich, but once Mussolini introduced a conference to settle differences, the Fuhrer had no choice but to attend and forgo Operation Green, the seizure of the Sudetenland and Czechoslovakia as a whole. Harris’ discussion raises the arguments of British historian A.J.P. Taylor whose 1961 book THE ORIGINS OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR was greeted with disdain at the time of its publication.

(satirical cartoon commenting on the Munich Conference)

For those with little or no knowledge of Munich the book will be a satisfying read, but for those a bit older with a knowledge of European history leading to the Second World War, the plot will be quite predictable.

(Chamberlain and Hitler)

/munich-agreement-large-56a61c5c3df78cf7728b64ee.jpg)