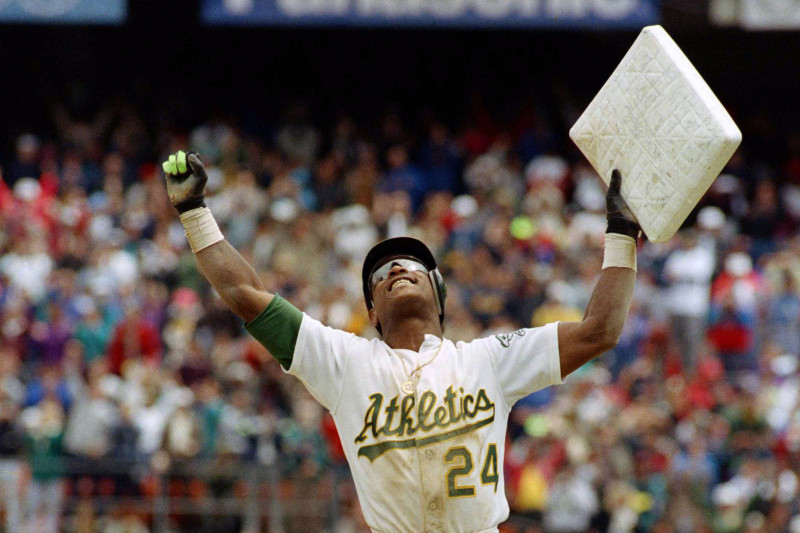

There are few more talented and interesting characters in baseball history than the enigmatic Rickey Henderson. Be it his personality or ego which dominated a number of clubhouses or his play on the baseball diamond one accurate description emerges, unchallenged talent and a desire to be the greatest or one of the greatest in baseball history. Henderson set the record for the most stolen baseball in a season, the most career runs scored, walks, the most lead off home runs, 3000 hits, earning a series of gold gloves and was a force in of himself. All of these accomplishments are captured by Howard Bryant in his latest book, RICKEY: THE LIFE AND LEGEND OF AN AMERICAN ORIGINAL, which is an apt title for his biography. Bryant has written a number of deeply researched and insightful books dealing with baseball and racism in American society. His JUICING THE GAME: DRUGS, POWER, AND THE FIGHT FOR THE SOUL OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL is a superb recounting and expose dealing with the steroid era in baseball; SHUT OUT: A STORY OF RACE AND BASEBALL IN BOSTON zeroes in on the Yawkey family and their role in making the Red Sox one of the most racist franchises in baseball history; FULL DISSIDENCE: NOTES FROM AN UNEVEN PLAYING FIELD uses baseball as a meditation on the idea that we are living in a post-racial America which he easily destroys; and THE HERO: A LIFE OF HENRY AARON which explores the life story of a different type of person and player than Henderson. Unlike Henderson, Aaron was not as flamboyant or controversial and was beloved for his dedication to his craft and “played baseball the right way,” not rubbing his peers the wrong way despite his talent and on field performance. In his latest effort, Bryant has prepared an intimate portrait of “the man of steal” discussing all aspects of his background, career, and life after many of his skills had eroded. What emerges is a very complex portrait of a man who thrilled baseball fans on a daily basis for over two decades.

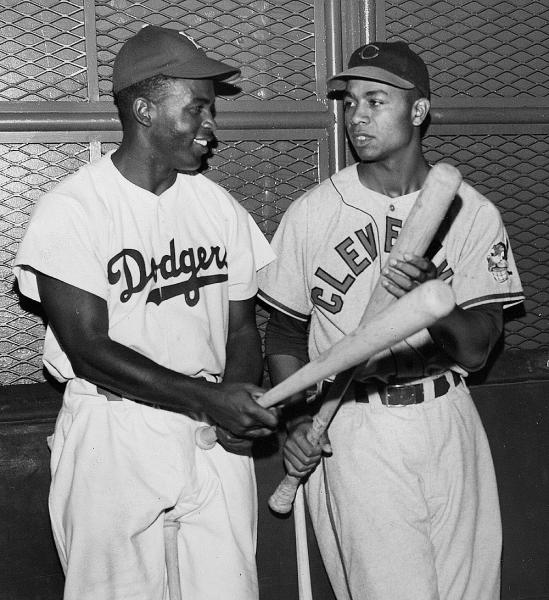

As in all of his books Bryant places his subject in the context of the civil rights movement and racism in sports. RICKEY is no exception as he presents Henderson’s early life story within the framework of white backlash against integration as he grew up in Pine Bluffs, AK, 45 minutes from Little Rock amidst the “Crisis at Central High School” in 1957 to Oakland, CA which became central to the black exodus from the south following World War II – in a sense the city was the black Ellis Island. In 1940 Oakland was 2.8% black and by 1950 81% of blacks living in the city were born in the south and followed the concept of “chain migration.” Bryant’s approach is a thoughtful one as he recounts why so many blacks migrated to Oakland. The lure of jobs at the docks and defense industry as World War II commenced became a lifeline for southern blacks to escape violence, murder, lynching’s and all the “accoutrements” of living in the racist south. It is fascinating to realize the baseball talent that accrued to Oakland as southern black families arrived. Hall of Fame sports figures such as Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, Joe Morgan, Curt Flood, Bill Russell, and Paul Silas all seemed to have the same migration background.

Bryant’s methodology toward sports biography is different than most. His portrayals are steeped in American history, especially white racism, the rise of the Civil Rights Movement, and the forces in American society and uses Oakland as a microcosm for white racism and the plight of the black community. It should not be a surprise that the Black Panther Movement of the 1960s and leaders such as Bobby Seale and Huey Newton hailed from Oakland. In the 1940s and 50s Oakland was 90% segregated and it is in this climate that the 10 year old Rickey Henderson arrived from Arkansas in 1969.

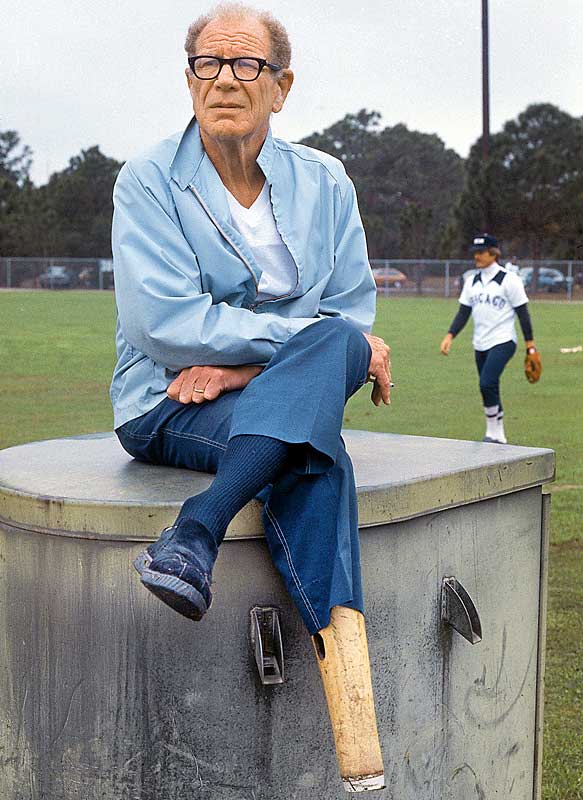

Bryant carefully traces Rickey’s early years and his path to the major leagues. Along the way we meet important personages like Charles O. Finley, the controversial and innovative owner of the Oakland A’s, Billy Martin, the abusive, racist, and brilliant manager of the team, Mike Norris, a pitcher who became Rickey’s best friend along with numerous characters that dominated baseball during Rickey’s career. Rickey was all about himself – what was his worth, and his overall goal of becoming the greatest base stealer of all time breaking Ty Cobb and Lou Brock’s records.

Rickey’s life story reflects the lack of education due to segregation to the point that Henderson never really learned how to read in school as with many black athlete’s teachers would pass them on despite not mastering basic reading and writing skills as long as they could perform on the field or the arena. Bryant explains this is why Rickey refused certain obligations knowing he could not read well and feared embarrassment and humiliation. “Rickey speaks,” or “Rickey being Rickey” was a reputation he acquired in large part because of his own inferiority when it came to private interaction or activities involving public speaking or reading.

According to Bryant Rickey burned to be great, but he was often a singular character, someone set apart from the rest. He was not one of the guys in the clubhouse and he showed none of the deference veterans expected. His lack of reverence was possibly a by-product of football being his number one choice as an athlete. Another reason was his belief in his own ability. He did not walk into the clubhouse in awe of everything baseball as many young players did. Thirdly, Rickey never forgot the day he was drafted and who was drafted ahead of him. He was chosen in the 4th round and believed he was a $100,000 ballplayer, not the $10,000 he signed for.

Billy Martin played an outsized role in Rickey’s development. Perhaps because they both hailed from Oakland and had a similar view of baseball they would get along except that Martin was a control freak who refused to give Rickey the “green light” to steal at will. Everything needed Martin’s approval, but it was under his managerial tenure that Rickey excelled and would break numerous records, which brought about Rickey’s resentment as his manager took a great deal of credit for his accomplishments. In the end it did not matter who his manager was, Rickey was fueled by his obsession with greatness.

Importantly, Bryant discusses Rickey’s “crouch” in the batter’s box which reduced his strike zone leading to increasing numbers of walks and steals as it forced pitchers to throw directly into his power. Outfielder Billy Sample described Rickey’s strike zone as that “of a matchbox.” Opposing players, umpires, particularly pitchers and catchers complained in vain, and Bryant’s vignettes are priceless. Rickey’s “style” made catchers look bad, increasing their hostility toward Rickey. When he slid into home they hit him hard, when pitchers tried to pick him off first basemen would slap on a tag to make him feel as uncomfortable as possible – but nothing stopped him. Rickey’s reputation as a “hot dog,” i.e., the development of his “snatch catch” was part of what he termed his “styling” something he had done since he was a kid, but according to Bryant many reporters evaluated his performance with a racial tone.

Bryant deftly places Henderson’s career and personality in the milieu of baseball history and carefully compares and contrasts him with others, contemporary and in the past. Stories about Joe DiMaggio, Lou Brock, Willie Wilson provide insights into Rickey’s approach to baseball and his amazing accomplishments. Different from others in his approach to his sport Rickey seemed to me in his own world. He would talk to himself in the batter’s box, he would stroll slowly to the plate, and had so many eccentric habits that a Yankee executive, Woody Woodward described him by saying, “I’ve never seen a guy look so fast in slow motion.”

For Rickey, the “unwritten rules of baseball” should never have been written! He went by a different drummer where his personal statistics were paramount. Bryant compares Rickey’s accomplishments with contemporaries like Tim Raines, Willie Wilson and James Lofton and despite their success they came up short. Rickey always measured himself against the accomplishments of others, particularly those he felt were a threat and these three individuals appear repeatedly in Bryant’s narrative.

At times Bryant digresses but does a wonderful job discussing Rickey’s relationship with managers such as Tony La Russa, who always believed and still does that he is the smartest man in the room, Buck Showalter, his New York Yankee manager who was considered a hard nosed manager, Bobby Valentine, the New York Mets Manager who Rickey held in disdain. Of course, Yankee owner George Steinbrenner appears, Dave Stewart, one of his closest friends, Jose Canseco, a home run hitter who Rickey saw as a buffoon, Reggie Jackson, a teammate in Oakland with an outsized ego, and Don Mattingly, a Yankee teammate who he admired among many portraits that are depicted. Bryant’s work is extremely entertaining and satisfying. It is well written as all of Bryant’s books and provides evidence for Rickey’s place in baseball history. The book is a great read just for all the “Rickey stories” and “Rickeyisms” he quotes. As his career evolved his reputation changed from a self-absorbed record seeker who in his late thirties became a beloved person whose feats and numbers spoke for themselves. Playing at a time when players were beginning to flex their legal muscle entering the age of free agency as owners could no longer control them for life, Rickey’s performance on the diamond cannot be challenged. An excellent read.