(The United Nations building in NYC)

As the American presidential election seems to creep closer and closer it is difficult to accept the idea that a substantial part of the electorate remains ignorant when it comes to knowledge of American foreign policy, or is apathetic when it comes to the issues at hand, or believe that Donald Trump has led the United States effectively in the realm of world affairs. It is in this environment that Richard Haass, the president of the Council of Foreign Relations, and author of a number of important books, including, WAR OF NECESSITY, WAR OF CHOICE: A MEMOIR OF TWO IRAQ WARS, and A WORLD IN DISSARAY: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY AND THE CRISIS OF THE OLD ORDER has written a primer for those interested in how international relations has unfolded over the last century, and what are the issues that United States faces today. The new book, THE WORLD: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION may be Haass’ most important monograph as he is trying to educate those people who have not had the opportunity to be exposed to his subject matter in the past, and make them more literate followers of international relations in the future.

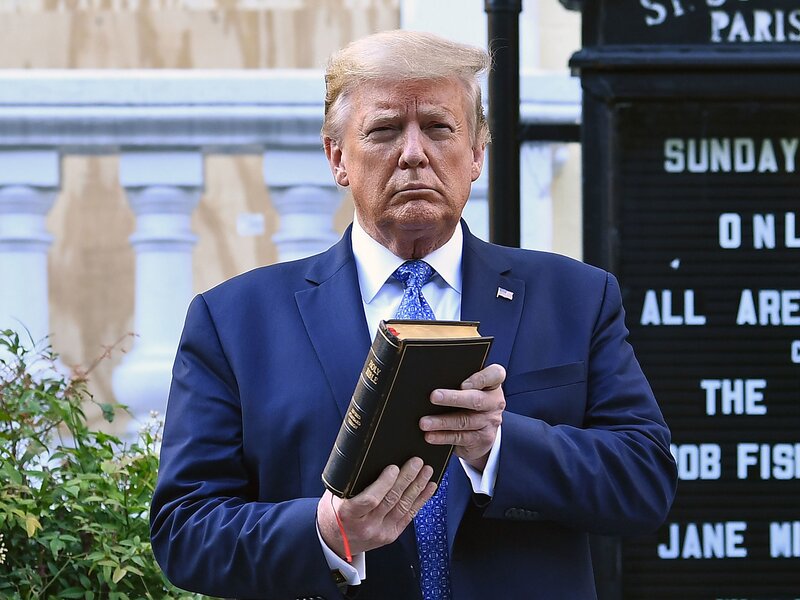

Haass states that his goal in writing his latest work is to provide the basics of what “you need to know about the world, to make yourself globally literate.” At a time when the teaching of and the knowledge of history and international relations is on the decline, Haass’ book is designed to fill a void. He focuses on “the ideas, issues, and institutions for a basic understanding of the world” which is especially important when the Trump administration has effectively tried to disassemble the foundation of US overseas interests brick by brick without paying attention to the needs of our allies, be they Kurds, NATO, the European Union, and most importantly the American people with trade deals that are so ineffective that $29 billion in taxpayer funds had to be given to farmers because of our tariff policy with China. Perhaps if people where more knowledgeable the reality of what our policy should be would replace the fantasy that currently exists.

|

|

Xi Jinping with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev on 28 September 2010

Xi Jinping with Russian President Dmitry Medvedev on 28 September 2010

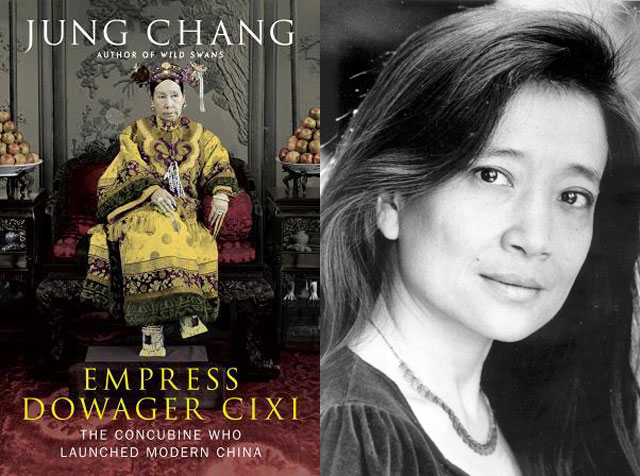

Haass has produced a primer on diplomatic and economic history worthy of a graduate seminar in the form of a monograph. Haass’ sources, interviews, and research are impeccable from his mastery of secondary materials like Henry Kissinger’s A WORLD RESTORED: METTERNICH, CASTLEREAGH, AND THE PROBLEMS OF PEACE, 1812-1822 and Jonathan Spence’s THE SEARCH FOR MODERN CHINA. Haass has created an educational tool that is a roadmap for those who would like to further their knowledge on a myriad of subjects. Further, the author offers a concluding chapter entitled, “Where Do You Go for More” which augments his endnotes that should be of great assistance to the reader.

(Vladimir Putin)

Haass’ writing is clear and evocative beginning with chapters that review the diplomatic history of a number of world regions which encompasses about half of the narrative. He returns to The Treaty of Westphalia which ended the Thirty Years War in 1648 as his starting point. Haass then divides history into four periods. First, the roughly three hundred years from the early seventeenth century to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Second, 1914 to the end of World War II in 1945. Third, the Cold War, roughly 1945 to 1989. Lastly, the post Cold War period to the present. In each section he reassesses the history, major players, and issues that confronted the world community at the time drawing conclusions that are well thought out and well grounded in fact, the opinion of others, and documentary materials available.

A case in point is Haass’ analysis of China focusing on her motivations based on its interaction with the west which was rather negative beginning with the Opium War in 1842 to the Communist victory in 1949. In large part, China’s past history explains her need for autocracy and an aggressive foreign policy. Haass delves into the US-Chinese relationship and how Beijing unlike Russia embraced integration with the world economy stressing trade and investment in the context of a state-controlled economy that provides China with advantages in domestic manufacturing and exports. A great deal of the book engages China in numerous areas whether discussing globalization, nuclear proliferation, trade, currency and monetary policy, development, and climate change. A great deal of the material encompasses arguments whether the 21st century will belong to Asia, with China replacing the United States as the dominant power on the globe. Haass does not support this concept and argues a more nuanced position that depending on the immediate political needs of both countries will determine the direction they choose. The key for Haass is that the United States must first get its own house in order.

Haass carefully explains the fissures in US-Russian relations as being centered on Vladimir Putin’s belief that his country has been humiliated since the fall of the Soviet Union. Haass’ argument is correct and straight forward as Putin rejected the liberal world that sought to bring democratic changes to Russia and integrate her economy into more of a world entity. Putin’s disdain and need to recreate a strong expansionist military power has led to the undermining of elections in the US and Europe. Putin’s “feelings” have been exacerbated by NATO actions in the Balkans in the 1990s and its expansion to include the membership of former Soviet satellites like Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. The end result is that Moscow pursued an aggressive policy in Georgia, the Crimea, and eastern Ukraine resulting in western sanctions which have done little to offset Putin’s mind set.

Haass is on firm ground when he develops the economic miracle that transpired in China, Taiwan, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea as the reduced role of the military in these societies, except for China have contributed greatly to their economic success. Their overall success which is evident today in how they have dealt with the Covid-19 pandemic is laudatory, but there are a number of pending problems. The China-Taiwan relationship is fraught with negativity. Japanese-Chinese claims in areas of the South China Sea and claims to certain islands is a dangerous situation, the current situation on the Korean peninsula is a problem that could get out of hand at any time. Lastly, we have witnessed the situation in Hong Kong on the nightly news the last few weeks.

The Syrian situation is effectively portrayed to highlight the tenuousness of international agreements. It is clear, except perhaps to John Bolton that the US invasion of Iraq has led to the erosion of American leadership in the Middle East. American primacy effectively ended when President Obama did not enforce his “red-line” threat concerning Bashir al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons, and President Trump’s feckless response to the use of these weapons in 2017. The result has been the elevation of Iran as a military and political force in the region, as well as strengthening Russia’s position as it has supported its Syrian ally in ruthless fashion. Haass’ conclusion regarding the region is dead on arguing that its future will be defined like its past, by “violence within and across borders, little freedom or democracy, and standards of living that lag behind much of the world.”

In most regions Haass’ remarks add depth and analysis to his presentation. This is not necessarily the case in Africa where his remarks at times are rather cursory. This approach is similar in dealing with Latin America, a region rife with drug cartels, unstable economies, and state weakness which is a challenge to the stability of most countries in the region.

One of the most useful aspects of the book despite its textbook type orientation is the breakdown of a number of concepts in international affairs and where each stand relative to their success. The discussion of globalization or interconnected markets has many positive aspects that include greater flows of workers across borders, tourism, trade, and sharing of information that can help negate issues like terrorism and pandemics. However, globalization also means that for certain issues like climate change borders do not matter. Global warming is a fact and though some agreements have been reached the self-interest of burgeoning economies like China and India that rely on coal are a roadblock to meaningful change. Interdependence can be mutually beneficial but also brings vulnerability, i.e., trade agreements can result in job loss in certain countries and increased unemployment, Covid 19 knows no borders, as was the case with the 2008 financial crisis. Haass is very skeptical that mitigation of climate change will have a large enough impact, he also discusses the negative aspects of the internet, and the world-wide refugee problem adding to a growing belief that future international relations will carry a heavy load and if not solved the planet will be in for major problems that include global health. Haass’ conclusions are somewhat clairvoyant as I write this review in the midst of a pandemic, which the author argues was inevitable.

Haass shifts his approach in the final section of the book where he considers diplomatic tools like alliances, international law, and vehicles like the United Nations as governments try and cope with the problems facing the world. In this section he focuses on the features of order and disorder or order v. anarchy to provide tools that are needed to understand both the state of play and the trends at the regional and global levels. He breaks down issues as to their positivity and negativity as he does in other areas of the book, but here he makes a case for American leadership supported by military power as the best hope for stability and progress. But even in making this argument, Haass presents certain caveats that must be considered. For example, do nations have the right to interfere in a sovereign country to prevent genocide, can a country’s sovereignty be violated if they are providing resources and protection to terrorist groups, or does an ethnically like minded people deserve to have their own country based on self-determination. Apart from these questions is the issue of enforcement. Does international law exist since there is no uniform vehicle to force compliance, and what tools are available to convince nations to support decisions by international bodies or groupings.

All in all Haass has written a primer for his readers, but does this audience even understand the complexities of foreign policy and do they have the will to learn about it and then elect representatives who themselves have a grasp of issues to direct the United States on a well-reasoned path that can maintain effective global activism? Only the future can answer that question, but for me I am not that optimistic in terms of the American electorates interest in the topic or its commitment to educating itself.

/nationalist-troops-on-ship-leaving-china-514869966-5c436fa6c9e77c0001f11040.jpg)