Today Ukraine burns and Republicans in the House of Representatives dither. The Speaker, Mike Johnson has emerged as a puppet of Donald J. Trump and refuses to bring to the House floor a bill passed by the Senate that would provide funding for the Kyiv government which would assist in preventing any further Russian gains on the battlefield. This seems to be part of Trump’s election strategy of not allowing any “Biden Political Wins” in addition to his commentary that when he resumes his presidency after the November election he would either withdraw from NATO and/or refuse to honor Article 5 of the NATO charter. He has further stated that if a NATO state were attacked his decision would be based on whether that country had “paid its bills.” In addition, the former president has encouraged Russian President Putin to attack any country of his choosing. This is where Mr. Trump stands today, but it is not much different from the attitude he espoused during his four years in the White House.

When Joseph Biden assumed the presidency in January 2021 he sought to undo the damage that the Trump administration had done to NATO and relations with our allies in general. The process of returning US foreign policy to its traditional post-World War II strategy, as the Biden administration was confronted with the growing isolationist wing of the Republican party is the main topic of Alexander Ward’s new book, THE INTERNATIONALISTS: THE FIGHT TO RESTORE AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY AFTER TRUMP. The post-war strategy as developed by Jake Sullivan, Biden’s National Security advisor would evolve into a new approach that centered on a “return to fundamentals: a healthy middle class powered by a humming industrial base, a humility about what the US military alone can accomplish, a solid cadre of allies, attention to the most existential threats, and a refresh of the tenets that sustain American democracy…an old road map to a new future.”

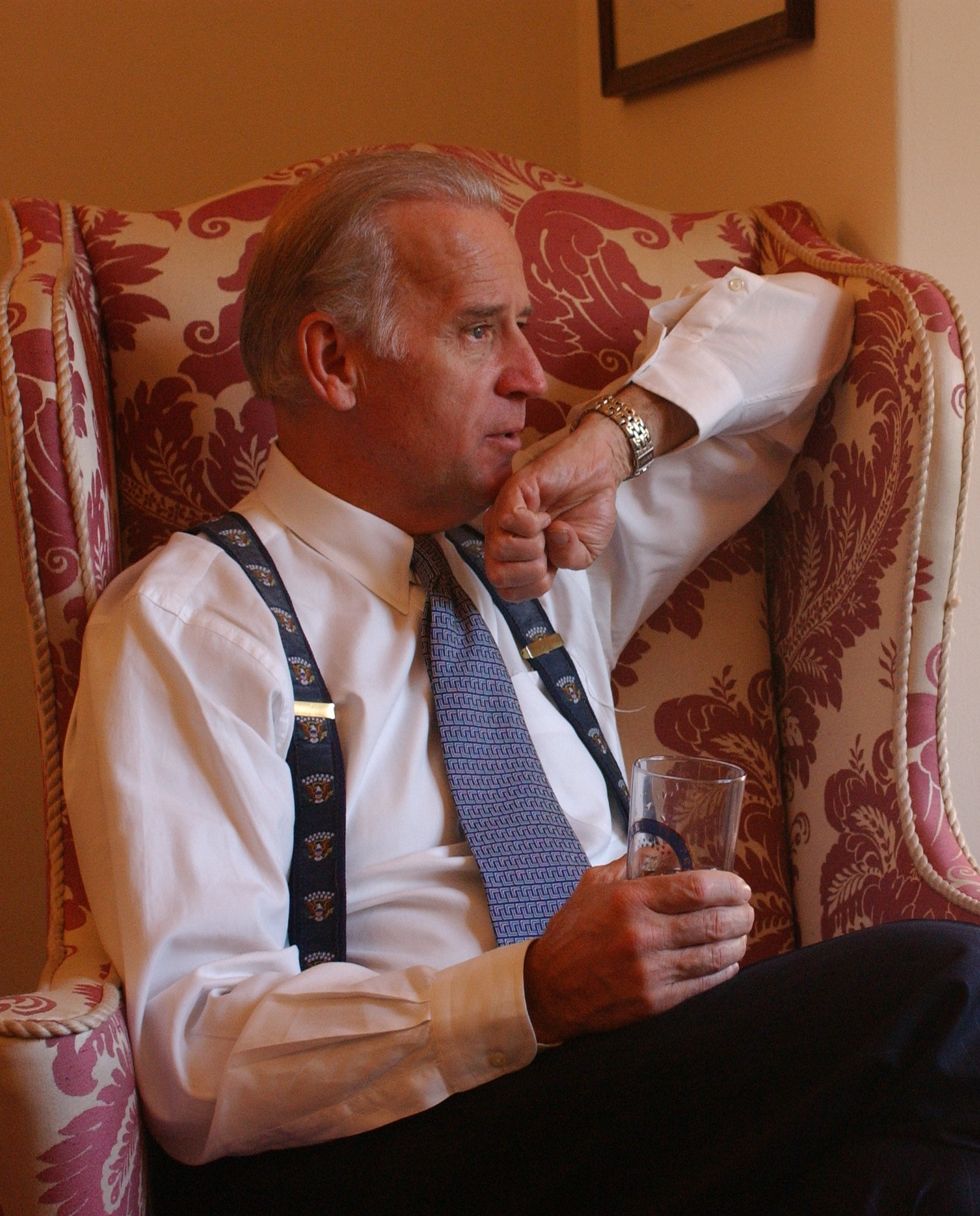

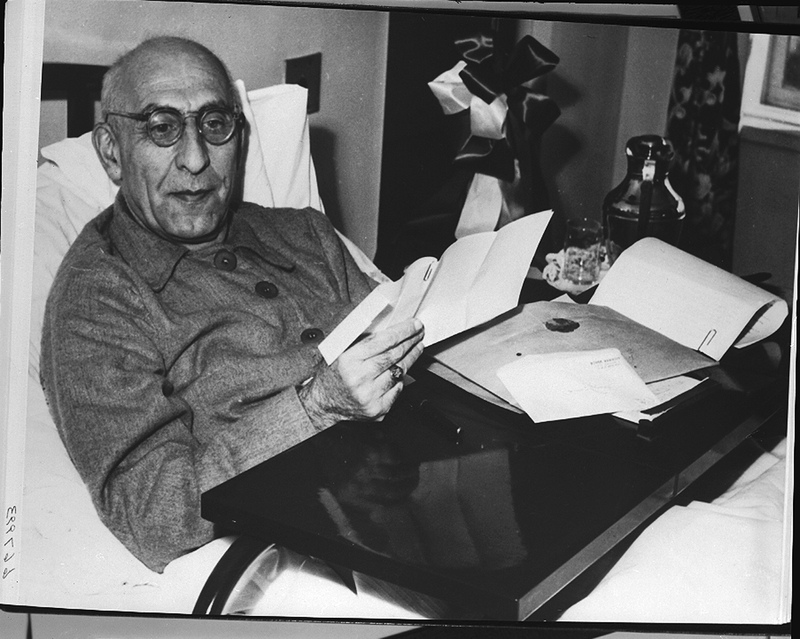

(National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan)

Ward, a national security reporter for Politico relies on interviews with the most important decision makers in the Biden administration and its allies and his own incisive analysis to offer the definitive account of American foreign policy from the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan to the current war in Ukraine initiated by Moscow. It reads as a first draft of history and its subject matter is of the utmost importance as Biden and his team were able to stabilize and reconstruct what Trump had damaged. What is clear is that should Trump regain the presidency all the work of the Biden administration will have been for nought, and America’s national security will clearly be endangered.

Ward begins with the understanding between individuals like Ben Rhodes, an Obama national security advisor, and Jake Sullivan, a Hillary Clinton advisor that to defeat Donald Trump in 2020 they needed to come together and create a “Shadow Foreign Policy Cabinet” to flush out a coherent foreign policy strategy which would become the basis for an infrastructure for the next presidential election. After delving into the career path of both men and Anthony Blinken, an advisor to Joe Biden since his Senate days Ward shifts his focus to the prevailing problems that Biden would face at the outset of his presidency – Afghanistan, Israeli-Hamas conflict, the war in Ukraine, the relationship with Russia, and a number of other critical issues.

(Secretary of State Anthony Blinken)

Overall Biden receives high marks from Ward except for the handling of America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. Relying on interviews with key players who argued for leaving a military presence in Afghanistan and those who favored a complete withdrawal. Biden’s position was clear from the get-go – an immediate withdrawal. Though he was hampered by Trump’s deal with the Taliban that stated that US forces would leave by May 1, 2021, Biden reopened negotiations with the Taliban in the hopes of obtaining their cooperation to facilitate the American departure. The Biden administration operated on the assumption that they had 18-24 months leeway before the Kabul government would collapse and the Taliban taking over. As events played out that intelligence was faulty and way off the mark as the Taliban would reach the outskirts of Kabul within weeks of the American drawdown.

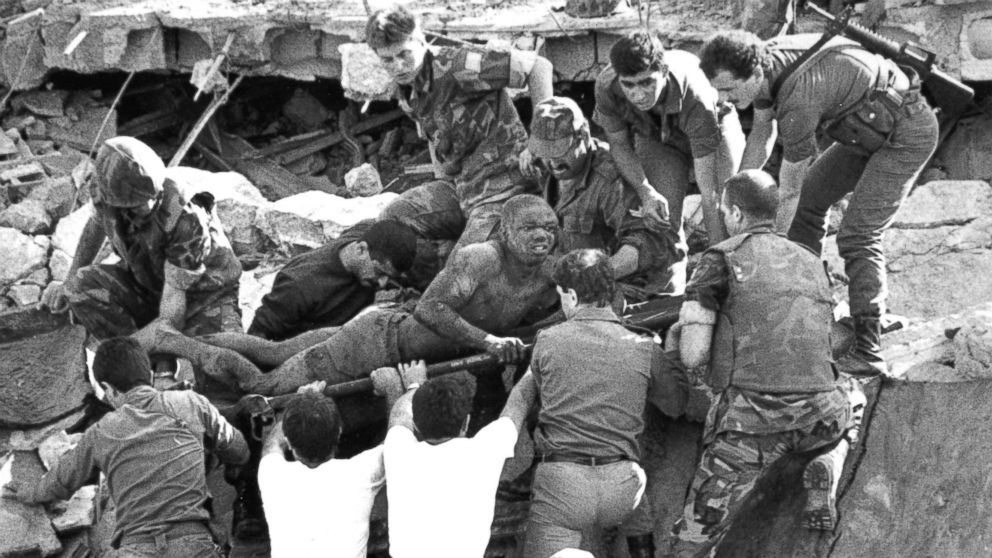

The Biden administration argued that we built and trained a 300,000 man army over a twenty year period and now many would not fight, allowing the Taliban to quickly march on Kabul. This created another problem in that there were at least 2500 individuals who worked for US forces over the years who would be in grave danger once the Taliban took over. The issue became SIVs (strategic immigrant visas) that were needed for the US military to transport them out of their country. Ward examines all aspects of the crisis that ensued which I can only crudely describe as a “cluster fuck” as American policy makers oversaw chaos and Biden’s greatest fear a visual similar to the April 1975 exit from South Vietnam as the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong captured Saigon. Biden would blame the Afghan military and its corrupt government in Kabul for the images of Afghans trying to escape the Taliban as they entered Kabul. There is no other description of Biden rationalizations and what transpired as humiliating. Biden firmly believed that the US would no longer commit itself to wars in the Middle East and Southwest Asia and it should use its influence and power to concentrate on the Russian and Chinese threat, but in reality Biden’s Afghan policy was “a failure of process and foresight.”

(The chaos of US withdrawal from Afghanistan, 2021)

Ward’s examination of the Ukrainian crisis reflects a president who wanted to support Ukraine in its conflict with Russia since Putin’s seizure of Crimea in 2014. He recreates the Biden-Zelensky relationship which did not get off on a strong footing. The former Ukrainian television personality believed that Biden was not taking the Russian threat seriously enough to allow Ukraine access to the sophisticated equipment that the current war proved was needed. Biden held back armaments and did not show the respect to Zelenskyy that the Ukrainian president believed he was entitled to. Relations deteriorated in 2021 as the US supported the completion of Nord Stream 2, a pipeline that would circumvent Ukraine and cost Kyiv over $2 billion a year in revenue. A Zelensky visit to Washington in September 2021 did little to improve Kyiv’s view of the Biden administration. Insufficient military aid and Biden’s full agenda with other world problems did not move Ukraine higher on the US foreign policy agenda. The Biden administration did so in order to rebuild relations with Germany which would benefit the most from the new pipeline because of Trump administration policies. No matter whose feelings were hurt it was clear by October 2021 with thousands of Russians troops on its border along with a massive amount of equipment according to US intelligence Putin was about to invade. The American response was to educate the world as to what Putin was planning and not be presented with a Russian fait accompli as they had been in 2014 over Crimea. As General Milley told Biden “We’re looking at a significant land invasion sometime in the coming months…The plan is to take down the country of Ukraine. It was the Russian version of shock and awe.”

In his discussion concerning Ukraine Ward focuses on President Zelensky. Despite repeated evidence of the coming invasion from December 2021 to February 24, 2022, Zelensky, according to Biden aides, was in “la-la land” in refusing to accept how dire the situation had become. Zelensky had convinced himself that no invasion was about to take place and the Biden administration’s public release of intelligence warning the world of Putin’s intentions was hurting the Ukrainian economy and scaring people to leave their country. This aspect of the book is important based on the west’s public posture of support toward Zelensky after the invasion took place when reality finally sunk in.

An early theme in Biden’s presidency was that the US needed to show democracy delivered for its people and could do the same for people worldwide by “steeling the liberal world order and curbing China’s growing influence….and keeping an aggressive Russia at bay.” The key was to rebuild relationships with European allies before it could confront Putin’s expansionism – Putin needed to know that the US and its allies were now working in concert. Biden’s message to Putin was that “confrontation and competition where needed, cooperation where policy” was the American approach. Once the two leaders met, Putin’s harangue about Ukraine and the fact that their people and the Russian population were one, NATO was a threat to Russian borders, and that American sanctions were not acceptable was clear. The key as mentioned was Germany and the recalibration of NATO even if Kyiv thought it was a betrayal.

Ward’s approach to dealing with Israel and his analysis is dead on. Biden had to overcome his past support for Israel that went back decades in the Senate and his personal relationship with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Biden did not want Secretary of State Anthony Blinken to be drawn into the cauldron of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as had occurred under John Kerry in the second Obama administration. Biden argued that it took too much air out of the room and left little for other prominent issues. The confrontation between the two sides at the outset of the administration was a precursor to the current war in Gaza. Biden wanted to stay out of clashes in East Jerusalem and he opposed the violence perpetrated by Israeli settlers in the West Bank. Biden had difficulty accepting the evictions of Palestinians from the West Bank and correctly warned that Hamas could only benefit. Under pressure from the left wing of the Democratic Party Biden finally came out and supported a two-state solution and the rights of Palestinians.

The events of October 7, 2023, proved that Netanyahu’s policies were faulty and designed to keep him in power and away from criminal prosecution. Biden’s abhorrence of what Hamas perpetrated on that day and public support was unquestioned. However, as Israeli disregard for Palestinian civilians in Gaza and the actions of settlers in the West Bank brought domestic and international pressure, Biden has had to put his unequivocal support for the Jewish state behind him and come out publicly for humanitarian aid, a two state solution, and criticizing Israel that its policies were detrimental to its future security needs.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/IYBL56FOENLK3N2DVRMF76ZIGY.jpg)

(Russian invasion of Ukraine, February 24, 2022)

As Ward tries to explain the underlying principles of Biden foreign policy he describes the personal and emotional platform of the president’s decision making. The role of his son, Beau’s death from cancer at the age of 46 always played a significant role in his father’s mindset. Biden firmly believed that the “burn pits” in Iraq contributed to his son’s death because of his service in Iraq. Biden deeply felt his son’s demise and did not want other parents to experience what he had – this mantra is ever present in Biden’s comments in the White House, the campaign trail, and general conversation.

Ward focuses on the Biden foreign policy team’s attempt to foster a new world view and how circumstances making such course corrections make it difficult. For the Biden team they were not blessed with the best of circumstances having to deal with Bibi Netanyahu. Vladimir Putin, and a corrupt and incompetent government in Kabul. The book itself relies heavily on sources in the State Department and the White House, and less so the Pentagon. The result is that the book is skewed toward staffer’s eye views and provides too much emphasis on Israel, Russia, Ukraine, and Afghanistan and less so China, climate change , Iran, immigration and supply chain issues.

The book illustrates the strength and weaknesses of personal diplomacy which Biden relies on heavily. His inability to influence Netanyahu, Putin, and former Afghan President Mohammad Ghani points to the need for greater reliance on a collective policy vision as personal ties are not always identical with national interests or political ones. This is clear as Biden could not influence Netanyahu’s right wing government or Putin’s plans to invade Ukraine.

Ward’s monograph is an important work of history in that it lays the groundwork for events he delves into that have continued today. These events have proven detrimental to Palestinians, Afghanis, and Ukrainians as the war in Gaza rages on, Russian indiscriminate bombing of Ukraine continues to foster terror, and the Taliban represses those who disagree with its harsh rule, especially women. As we move closer to the 2024 presidential election these issues will still be at the forefront of the news cycle and it will be interesting to see if Trump’s “America First “approach to international relations or Biden’s attempts to rekindle America’s place in the world will win out. No matter the result, the issue of democracy at home and a liberal internationalist agenda abroad are at stake.

(President Biden and his son Beau)

![June 3, 1961: Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, left, and U.S. President John F. Kennedy sit in the residence of the U.S. ambassador in Vienna, Austria, at the start of their historic talks. [AP/Wide World Photo]](https://2009-2017.state.gov/cms_images/7khruschev_kennedy1_600.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/portrait-of-the-kennedy-family-at-home-51379912-217f87c014704f659997064087973d4f.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/7FMIBPGJGZHELODTJZZ67EIR4U)

![People arriving from Afghanistan make their way at the Friendship Gate crossing point at the Pakistan-Afghanistan border town of Chaman [Abdul Khaliq Achakzai/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2021-08-15T143158Z_1093398639_RC2Q5P9W5VTP_RTRMADP_3_AFGHANISTAN-CONFLICT-PAKISTAN.jpg?resize=770%2C513)

+4

+4 +

+