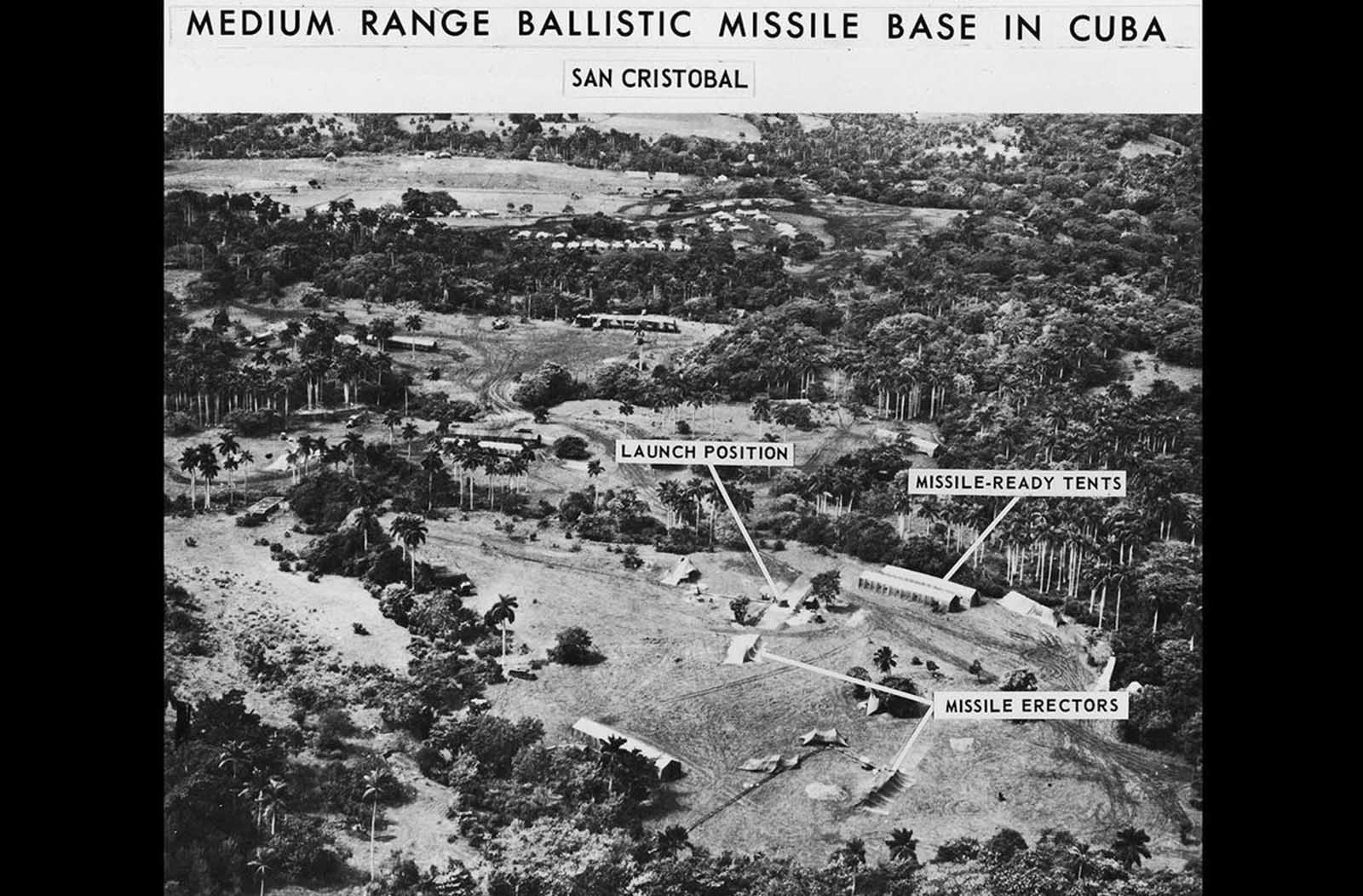

(Oliver Cromwell)

If one is looking for a volume that encompasses history with a touch of fiction to round out the storyline then Robert Harris is an author to be considered. Of the many novels that Harris has written including a trilogy about the struggle for power in ancient Rome; FATHERLAND which raises the possibility of a deal between Adolf Hitler and President Joseph P. Kennedy in 1964; ARCHANGEL, which focuses on the northern Russian port that hides Joseph Stalin’s secrets; AN OFFICER AND A SPY, centers around the Dreyfus Affair in 1890s France; V2, spotlights the Nazi missile program during World War II; MUNICH which delves into the September, 1939 conference which took place at the height of Anglo-French appeasement before World War II; and my favorite, CONCLAVE concentrating on the Vatican machinations in electing a new Pope.

Harris’ fifteenth and latest novel is his first foray set predominantly in America, ACT OF OBLIVION which begins in 1660 England where Colonel Edward Whalley and his son-in-law Colonel William Goffe flee England accused of being part of the plot that resulted in the execution of Charles I that marked the culmination of the English Civil War and the restoration of Charles II to the English throne. As in all of his novels, Harris has the unique ability to blend historical figures with his own creations, developing absorbing plots that are counter factual at times, but also toes the historical line. If you enjoy John Le Carrie, Alan Furst, Martin Cruz Smith, David Liss, Ken Follet or Len Deighton, Harris’ work will prove most satisfying as he possesses an uncanny knowledge of the historical period he chooses to develop for his stories based on sound research and character development.

In his current effort Harris begins by introducing the reader to the general outline of the English Civil War in the 17th century that resulted in the beheading of Charles I on January 30, 1649, bringing to power Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector. The trial of Charles I and his ultimate death brought about a written death warrant, the Act of Oblivion that was signed by 59 men, including members of Parliament, Cromwell’s New Modern Army, and important politicians of the period. Two of the signees were Colonel Edward (Ned) Whalley and his son-in-law, Colonel William Goffe. As the novel evolves 57 of the 59 were either captured and executed, died of natural causes, or committed suicide. Whalley and Goffe are the two that remained alive after Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660. Enter Richard Naylor, one of the few made up characters in the story whose role throughout the novel is to hunt down any remaining regicides.

The backdrop to the novel is religion and politics. All the characters seem deeply religious, particularly Whalley and Goffe and those who would hide them from Naylor and the Privy Council. Religion permeates the dialogue, politics, and emotions of the day as prayer, meeting houses, and conflict between Catholics and Puritans appear regularly as the story unfolds. Whalley and Goffe escape England and leave their families in 1660 as they are about to be arrested. This begins an odyssey that takes them across the Atlantic to Boston and into the Connecticut Valley hiding in Guilford, Hartford, and New Haven, Connecticut, and later Hadley, Massachusetts.

Along the way Harris does a superb job developing characters such as John Davenport who led the New Haven colony and saw it as “God’s millennial kingdom;” Captain Thomas Breedon, a royalist, rich merchant; Sir George Downing, a chaplain in Cromwell’s army who turned out to be an English spy; John Ditwell, a member of parliament and judge at Charles I’s trial; Dan Gookin, lived near Harvard College and escorted Whalley and Goffe to America, and the Reverend John Russell, the leading political and religious figure in Hadley, Massachusetts. There are many more characters, the most important being Naylor who takes on a role similar to Jean Valjean in Les Misérables, as his intrepid nature and personal tragedy leads him to follow Whalley and Goffe from England to the New England colonies, Dutch New Amsterdam, Holland, at first by himself and a few others, later to return with four men o’war.

Harris’ character portrayals allow the reader to feel they know these individuals and their thoughts. Harris spares no detail in telling his story and he is able to fill in the historical gaps by employing Colonel Whalley as he writes his memoir that includes his family, but most importantly fighting for Cromwell in the English Civil War and the reign that followed. Harris’ portrait seems based on the biography of Cromwell written by historian Antonia Fraser and is balanced and accurate. As Harris develops these characters he displays the lack of scruples revealed by many self-appointed Puritan ministers, those who fought for Cromwell and switched to support the restoration of Charles II, Royalist and Roundhead spies and a host of others.

Over time as Naylor fails to bring the two remaining regicides to England, the Lord Chancellor, Sir Edward Hyde orders him to end his search and become his private secretary as the English people have moved on from capturing Whalley and Goffe. From that point on Harris focuses on Whalley and Goffe’s lives and actions as they still must remain in hiding.

Harris has excellent command of historical events and movements. He is able to weave the British seizure of New Amsterdam and the resulting Anglo-Dutch naval war, the return to plague to England in 1665, the Great London Fire of 1666, and King Philip’s War of 1774 into his story that enhances the legitimacy of Harris’ work. Other aspects that opened this reader’s eyes was the detailed description of how the regicides were executed. English barbarism is on full display as bodies were dismembered and some body parts were returned to families as a warning. The battles of the English Civil War are carefully described highlighting Cromwell’s strategy and the roles of Whalley and Goffe. Also important, is how Harris paints the difficulties faced by colonists who left England for America. Harris follows them into the western interior and analyzes why they settled where they did, how they dealt with Native-Americans, their survival of brutal winters, and their ability to grow food and ultimately build settlements.

(The Execution of Charles I of England / Artist unknown, Wikimedia // Public Domain)

Harris has written a fast paced wonderfully detailed story of a modern manhunt that weaves between Restoration era London and pre-revolutionary New England. Harris brings the past to life through the writing and dialogue of his characters and personal details such as scratchy wigs, rough leather boots, and the sparseness in which people lived. To his credit Harris does not allow himself to become entrapped by Christian doctrine in his storytelling and concentrates on the simplicity of faith and the anti-monarchical feelings of characters who will find a natural home among the dissenters and Puritans in New England. ACT OF OBLIVION is a wonderful novel about a divided nation whose people suffer from physical and emotional wounds caused by war. As Alex Preston writes in his The Guardian review of August 30, 2022, Harris has authored an important novel in that it shows the power of forgiveness and the intolerable burden of long-held grudges.

(Oliver Cromwell)

![June 3, 1961: Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, left, and U.S. President John F. Kennedy sit in the residence of the U.S. ambassador in Vienna, Austria, at the start of their historic talks. [AP/Wide World Photo]](https://2009-2017.state.gov/cms_images/7khruschev_kennedy1_600.jpg)