(Claude Monet)

The work of artists who enter their declining years is not usually positive fodder for biographers, but Claude Monet’s later years is one of the exceptions as depicted in Ross King’s book, MAD ENCHANTMENT. King who has written a number of interesting books dealing with art history, including, BRUNELLESCHI’S DOME, MICHELANGELO AND THE POPE’S CEILING, and LEONARDO AND THE LAST SUPPER begins his narrative by pointing out that once Monet reached his sixties and seventies, he had achieved great wealth, notoriety, and produced numerous career defining works. For years rejected by conservative critics and the new Avant Garde Cubists, Monet would find himself producing his Grande Decoration, consisting of eight waterlily murals during the World War I period.

King does an exceptional job reviewing Monet’s life and career up to 1914 when the French artist decided to return to painting after a four-year hiatus due to a series of tragedies. First, his loving second wife, Alice passed away in 1908, then in 1914 his son Jean died, in addition, he began to suffer from cataracts and in 1912 his vision began to decline. During this period a group of his friends also passed, including; Manet, Renoir, Rodin, Pissarro, and Cezanne. Monet still had a number of friends remaining who he could lean on, chief among them was Georges Clemenceau, the French journalist, politician, and man of letters. Clemenceau would support Monet emotionally throughout his life and encouraged him to renew his painting after a visit in early 1914.

One of the most important components of the book is King’s quasi-biography of Clemenceau within the larger narrative of Monet’s life. The later French Prime Minister nicknamed “the Tiger” helped lead France to victory in World War I and would become their voice at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. King uses Clemenceau as a vehicle to integrate French history with Monet’s life story and career and provides the reader the context of how major events affected Monet, how he responded, and their results.

There are a number of turning points in Monet’s life that King delves into. The first is the purchase of Le Pressair in the village of Giverny in 1890, a transaction that did not go over well with local farmers who resented his plan to divert the River Ru and purchase adjoining land to create the large pond on which to plant his water lilies providing him with his subject to paint. The locals saw no commercial benefit in these paintings and resented him as an outsider. Monet’s cantankerous personality also did not endear him to the locals.

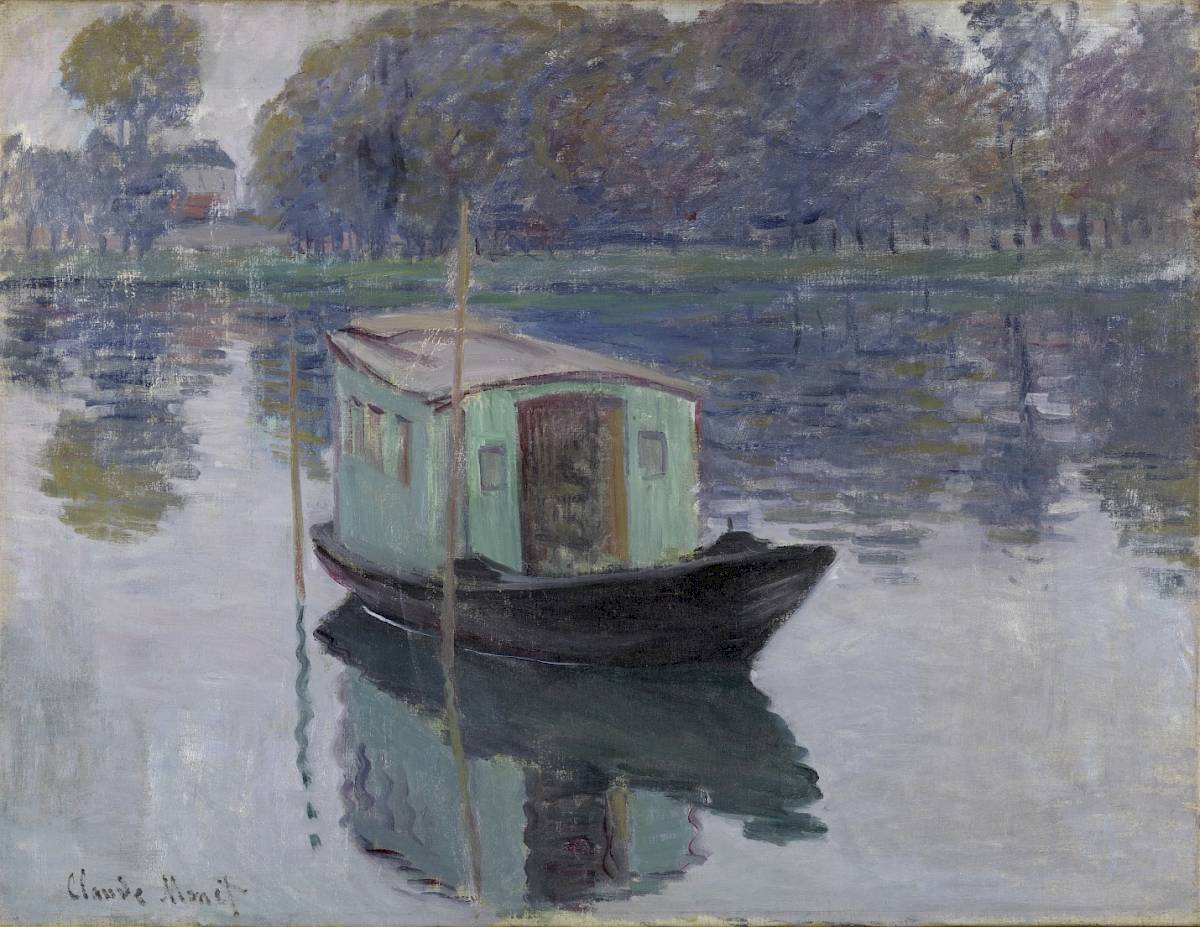

(The Studio Boat, 1874)

The second turning point for Monet was his reaction to the Dreyfus Affair in 1898. Up until that point, Monet’s paintings depicted rural France, deemed as a patriotic message through his art. Along with his friends, Emile Zola, Georges Clemenceau, and other Dreyfusards he rejected and criticized the rise in right-wing French anti-Semitism throughout the 1890s, as well as the unjust conviction of Captain Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French Army for spying for Germany. Monet decided he would no longer paint rural scenes that could be interpreted as patriotic and concentrate on developing his gardens and canvases.

King accurately points out a number of contradictions when it came to Monet as an artist. First, he wished to work in warm, sunny, and calm conditions, yet much of his career his place of choice to paint was Normandy whose weather was cool and damp for long periods of time. Second, he loved to paint, yet he claimed to find it, “unremittingly torture.” But this torture, friends pointed out was the key that drove him to perfection. King does a wonderful job describing Monet’s methodology and philosophy of painting throughout the narrative, I.e. Monet would paint twelve separate canvases at a time while preparing his Grande Decoration and rotate them on wheels according to the light in order to capture what he hoped to represent. Monet’s health greatly impacted his work in his later years as he was a victim of fatigue and neurasthenia even though to outsiders, he appeared hale and hearty most of the time. His maladies were greatly affected by the weather, which many times he refused to give into resulting in a negative impact on his health.

(Rouen Cathedral, 1894)

King approaches his explanation of Impressionism very carefully arguing that Impressionist artists “conspicuously called attention to their brushes and paints. They fragmented their brushstrokes into flickering touches of color that seemed to dissolve their painted worlds into shimmering mirages.” Canvases were not meant to be viewed at close range. King’s discussion of Monet’s painting of the Rouen Cathedral in 1894 with the proposed commission by the state of France to paint the damage caused by German shelling to the Cathedral at Rheims is illustrative of this point. Monet’s Impressionist approach would not be the best way to depict the savagery of German artillery on the cathedral for a government which wanted to heighten French distaste for the “barbaric Germans.” But, for Monet who always wished to receive a commission by the government this was not an acceptable argument, despite the “fuzzy envelope” that seemed to surround the objects that were represented.

(Monet’s Gardens at Giverny)

The most important event that impacted Monet’s later years was World War I. Monet’s travel and work would have to consider the effects of the war. Art supplies, food, petrol was all rationed and in short supply. A further reason for a state commission would allow Monet to receive coal, food, and materials for his canvases that others could not obtain.

King takes the reader to the Louvre which housed many of Monet’s and his fellow Impressionist friend’s paintings. He reviews the political and economic considerations involved and how German bombardment of Paris, and at times fears of a German attack on the city affected these artists. King provides a unique description and perspective of Paris during the war. Interestingly the fighting produced a war of words between German and French intellectuals over wartime accusations of barbarism. Monet was even recruited to lend his name to these efforts as French intellectuals produced a book entitled, THE GERMANS: DESTROYERS OF CATHEDRALS AND THE TREASURES OF THE PAST.

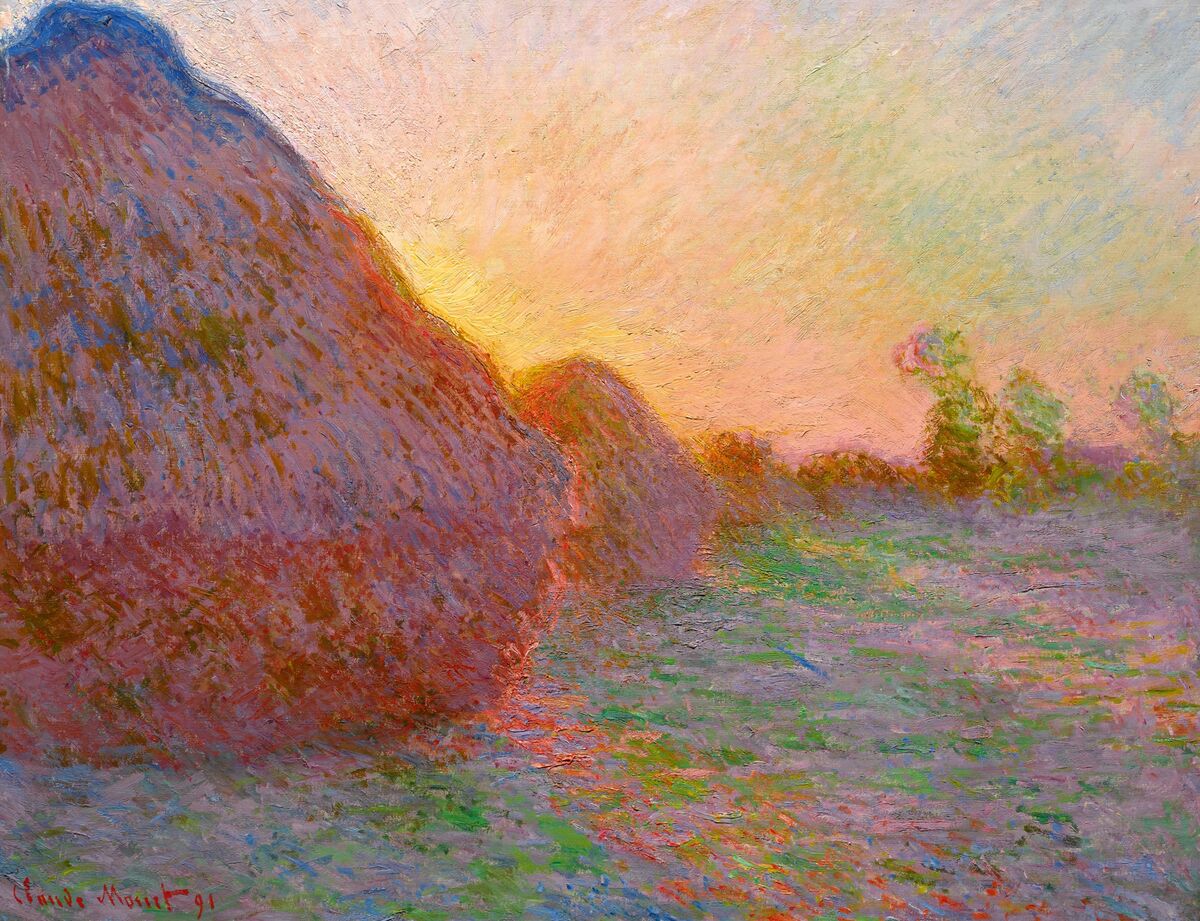

(Haystack Painting 1890/91)

The war also impacted Monet’s personal life, particularly his anguish over his paintings and his family. Monet refused to leave Giverny during the war as he stated he would rather die among his canvases and life’s work than depart. He also feared for his son Jeanne-Pierre who was in the army as was his son-in-law Albert Salerou. His son Michel would not enter the army until later in the war and would participate in the fighting. It easy for the reader to follow the course of the war as King describes Monet’s life and his interactions with his close friend Georges Clemenceau, I.e., the two battles of the Marne, and the Battle at Verdun, along with its overall impact on Monet and France in general.

(Portrait of a Painter)

The war also galvanized Monet, with a friendly push from Clemenceau to complete the Grande Decoration which according to Kathryn Hughes writing in The Guardian (3 September 2016) there was nothing remotely optimistic or even particularly French about the massive painting that stretched to over 300 feet. It is as Deborah Solomon points out in the New York Times (December 2, 2016) among art history’s greatest last acts as “the water lilies dispense with contours and boundaries and veer toward abstraction.” It is important to note that the subject of Monet’s painting was a garden and pond that was man made and contained hothouse cultivars from South America and Egypt and not a natural outcrop of rural France.

King introduces an important discussion of how tastes in art changed because of the war and the impact of the death of over 300 artists. According to art historian Kenneth Silver, the public and the painters would turn their backs on daring innovation. For many Frenchmen, Cubism and other forms of pre-war art were wild experiments and adventures that were seen as specifically German, and therefore, not to be replicated after the war. At the end of the war Monet offered to donate some of his paintings to the people of France and eventually the lily paintings were installed on specially constructed, curved walls at the Musee de l”Orangerie in Paris. The donation and the negotiations exacerbated by Monet’s need to control how the building would be prepared to receive and maintain his paintings are an integral part of the narrative as King relates his subject’s state of mind and physical health, particularly issues with his vision that led to a number of painful operations.

(Monet’s close friend and supporter, Georges Clemenceau)

Solomon sums up her review by arguing that “the book is short on analysis and fails to definitively explain the role played by Monet’s illness in the development of his late style.” But overall King has written a useful book that shatters the myth that Monet painted his Grande Decoration in seclusion when in fact people surrounded him. A staff of gardeners, his granddaughter Blanche, and others all impacted his life, and no one can take away anything from the gift that Monet has produced for posterity.

(Monet working on his Grande Decoration)