Of all the decisions made by President Biden during his first two years in office the most frequently criticized by both Democrats and Republicans was his decision to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan. Biden has wanted to end the American role in Afghanistan since his time as Vice-President thus the decision was not surprising. After two decades of war Biden had enough of the corruption, duplicity, and the lack of will to fight on the part of various Afghan governments to defeat the Taliban. It was not so much Biden’s decision to withdraw, but how it came about and how it was implemented resulting in negative repercussions for American foreign policy that has drawn so much criticism.

One of the first books to emerge since the end of American participation in Afghanistan is Elliot Ackerman’s THE FIFTH ACT: AMERICA’S END IN AFGHANISTAN. The book is broken down into five acts, the last resulting in the final escape of an Afghan family. Ackerman’s work is a combination of a meditation on war as a concept, a personal memoir, and his frustration with four presidential administrations. Ackerman has authored five novels following his career as a US Marine where he did tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan. After ending his time as a Marine officer, he joined the CIA and returned to Afghanistan as a paramilitary officer. His military career ended over a decade ago, but events in Kabul in August, 2021 as the Taliban closed in on the Afghan capital he found himself drawn back into what certainly was the end of an American quagmire.

(About 640 Afghans and others fleeing Afghanistan crammed into a U.S. Air Force C-17 cargo plane out of Kabul, August, 2021)

Ackerman’s narrative begins on a family vacation in Italy at the same time that thousands of Afghans who worked with American troops during the war as interpreters, spotters, and other capacities are trying to flee the country knowing full well that if they were captured by the Taliban their lives and the lives of their families would be in great danger. Ackerman proceeds to structure the novel by alternating a description of his family vacation, returning to certain segments of his time in the war zone, trying to assist Afghanis trying to flee the Taliban by contacting numerous individuals he served with, and lastly, providing what appears to be his private meditation of Afghanistan and war in general.

The most interesting aspects of the book revolves around Ackerman’s thoughts concerning the definition of war, how one determines victory or defeat, the cost of recovering the bodies of American soldiers, the differences between targeted killing and assassination, and trying to determine if the American people and society should share a major part of the blame for how the war transpired and finally ended for the United States.

Ackerman’s willingness to assist in trying to save as many Afghans as possible is supported by his wife and he is able to compartmentalize his obligations to his family and what he believes is his obligation to save as many people as possible. As the narrative evolves Ackerman’s commentary is perceptive and accurate. His comparison of the negotiations that ended the war in Vietnam under President Nixon, and those by President Trump with the Taliban are dead on. The negotiations led by Henry Kissinger that resulted in the 1973 Paris Accords cut out the South Vietnamese government and the final terms were presented as a fait accompli to President Nguyen Van Thieu. Similarly, American negotiators treated Kabul in the same way. The Doha Agreement signed on February 29, 2020 with the Taliban fatally delegitimized Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and his central government.

The concept of a citizen army and that of a volunteer force is examined very carefully. Ackerman correctly concludes that the American people, other than those who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan had “little skin in the game.” Both wars were financed through deficit spending and sparked varying degrees of disinterest in the course of the wars. During Vietnam the draft and the increasing cost of the war greatly contributed to the anti-war movement. In the case of the last twenty years there was no “war tax” or draft to galvanize the American people resulting in “a lack of interest” on their part or what some have referred to as “war fatigue.”

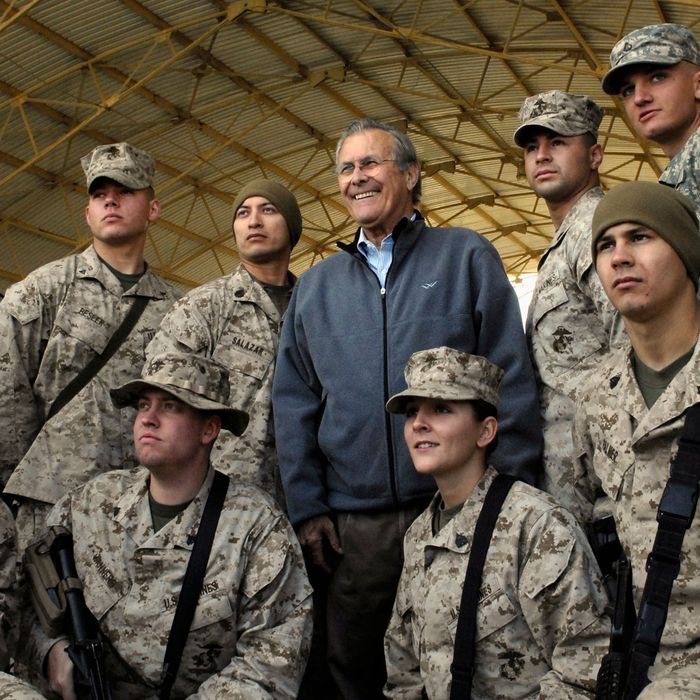

(Elliot Ackerman, Fallujah, Iraq, 2004)

Ackerman’s account contains a number of warnings for the American people. One of the most important is the role of the military in civil society. Ackerman writes that currently the military remains one of the most trusted institutions in the United States and one of the few that the public sees as having “no overt political bias.” However in the last few years that belief has been challenged by President Trump when he tried to use the military as a political vehicle to rally the support of what he perceived to be patriotic Americans. His photo op using soldiers at Lafayette Square on June 1, 2020 is a classic example. The George Floyd murder saw the use of National Guard troops to make a political point. Repeated calls by Trump to use what he termed “his military” for his own personal benefit was extremely dangerous. Up until now we have skirted this issue, but the increasing partisan nature of our domestic politics could some day result in a more dangerous version of January 6th. By the election of 2020 more and more retired military have become talking heads and it seems that the politicalization of the military is approaching. This is very dangerous especially when one party argues that an election was stolen and almost half the country believes that argument. What I fear is when this politicalization seeps down into the ranks and soldiers are called on to deal with election protests the possible result of such a scenario is something I do not want to envision.

As the narrative evolves the author’s empathy and guilt dealing with the end of the war and the fears of the Afghan people of the Taliban is totally evident. As he fielded phone calls, emails, and texts he is confounded as he tries to respond with strategies, employing his contacts, and doing whatever he can to help. This is juxtaposed throughout the book with his own combat experiences during his service in the Marines. The book is not a history of the final evacuation but it is more of a former soldier contemplating the meaning of the end for America’s fighting men and women. He focuses on the “should’ve and could’ve” aspects of war pertaining to himself, the men and women he fought with, and the decision makers in Washington. He concludes that we must question America’s judgement when it comes to Iraq and Afghanistan.

Overall, Ackerman’s work should provoke an extensive reevaluation of America’s approach to war – how we pay for it, what segment of society fights, and the impact of partisanship. The book is well written and provides a clear picture of two decades of war, how these wars ended, when the United States should resort to the use of force, and what our experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan mean for America’s future. I highly recommend it to all – there are many lessons to be learned.

(August, 2021. Afghans trying to reach Kabul airport to escape the Taliban as US troops withdraw)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/7FMIBPGJGZHELODTJZZ67EIR4U)

![People arriving from Afghanistan make their way at the Friendship Gate crossing point at the Pakistan-Afghanistan border town of Chaman [Abdul Khaliq Achakzai/Reuters]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2021-08-15T143158Z_1093398639_RC2Q5P9W5VTP_RTRMADP_3_AFGHANISTAN-CONFLICT-PAKISTAN.jpg?resize=770%2C513)

+4

+4 +

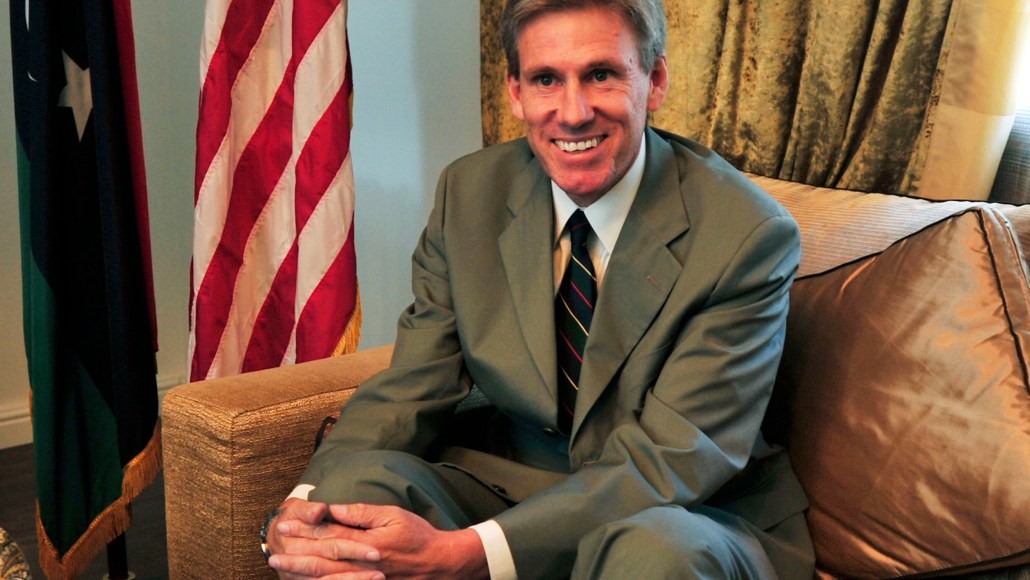

+ (American Ambassador to Libya Christopher Steven)

(American Ambassador to Libya Christopher Steven)

(Egyptian demonstrations against American Ambassador Anne Patterson)

(Egyptian demonstrations against American Ambassador Anne Patterson)