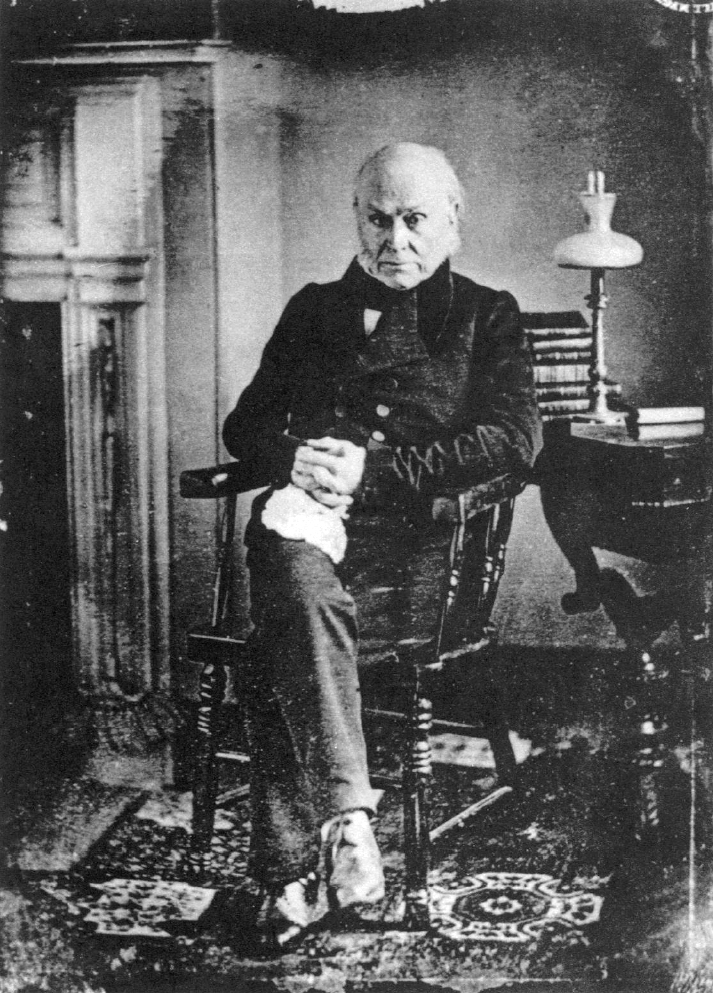

(John Quincy Adams, the 6th President of the United States)

At a time when most Americans believe they are witnessing the most divisive political campaign they have ever experienced, they need only to turn the clock back to the 1828 presidential campaign when Andrew Jackson, angry because he believed the previous election had been stolen because of a “corrupt bargain” between John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay, launched a nasty and personal attack against Adams as early as his inauguration resulting in Jackson’s eventual victory. This political clash is just one component of James Traub’s excellent new biography, JOHN QUINCY ADAMS: MILITANT SPIRIT. Adam’s the son of our second president was a rather enigmatic and recalcitrant figure who seemed to always answer to principle, not political expediency. His diplomatic career consisted of ministerial posts in the Netherlands, Prussia, Russia, England, as well as serving as Secretary of State. His political offices included the Massachusetts State Senate, the U.S. House of Representatives, and the Presidency. Adams’ life is a compendium of late 18th and 19th century events where he usually was a focal point in any important situation. This amazing career is skillfully portrayed by Traub as he dissects his subjects’ life and concludes that despite numerous achievements and failures, he never wavered from the moral convictions instilled in him by his parents, John and Abigail Adams.

(Abigail and John Adams, John Quincy’s parents)

The success of Traub’s effort lies in mining the 15,000 pages of Adams’ journal that he kept over his entire life. The fact that the journal has been digitized allows the author easy access and assisted in creating a window into his subject’s mind that is fascinating. Traub explores every aspect of Adams’ life, especially his close relationship with both of his parents. The reader can eavesdrop on conversations between the father and son where we see why Adams’ became the man he did. Not quite a reincarnation of his father, but strikingly similar. Many of the letters and conversations between mother and son are also available and we are exposed to the rigid moral principles and advice that Abigail offered. The type of father Adams’ became later in life is directly related to his own upbringing as he pursued the same method of childrearing as his parents. As far as his relationship with his wife Louisa it does not measure up to the closeness between John and Abigail Adams. He was a distant husband and Louisa and John Quincy spent many years apart.

At a very young age he “followed a set of standards, moral, and intellectual, to which people should be held, and he found much of the world wanting,” particularly women. The pressure on Adams because of his parents was immense and this led to feelings of guilt and depressive episodes. Many times he felt conflicted as he passed back and forth between aspiration and resignation. Traub has the knack of interweaving Adams’ private life with his career in an interesting fashion. We get a glimpse of all aspects of Adams be it in the family, years of diplomacy overseas, and his political career. Traub’s careful devotion to detail creates an accurate portrayal of life on the family farm in Quincy, MA, Washington, DC, or the many countries that he served as a diplomat.

(Louisa Adams, wife of John Quincy Adams who would outlive him by four years)

Adams was a much more pragmatic politician for his time and tried to stay away from rigid ideologues. For example, he refused to join the Federalists in their attacks on Thomas Jefferson, a man he admired, and supported the purchase of Louisiana because for Adams, unlike today, country came first, not political partisanship. Adams even supported Jefferson’s Embargo Acts (1807) when the New England region that he represented opposed it. As Traub states “he would become an honorable outcast like his father.”

Traub does a masterful job explaining how Louisa endured her domineering husband. The author’s narrative reflects a great deal of empathy toward Louisa as she tries to live apart from her sons for long periods of time while her husband was posted overseas. This in conjunction to the many disappointments the couple endured, from separation, countless miscarriages, and the death of their daughter Louisa, and their two sons John and George, but as their marriage endured John Quincy and Louisa would grow somewhat closer.

(Charles Francis Adams, the son of John Quincy that was most similar to his father)

Traub delves into all aspects of Adams’ diplomatic career. His most important postings dealt with negotiations to end the War of 1812, as minister to England, and his work in St. Petersburg as he established a close and friendly relationship with Alexander I which proved very important during the period of Napoleon’s defeat and the establishment of the Holy Alliance. Adams’ stint as Secretary of State is covered completely and the chapter devoted to negotiations with the British and concerns over the rise of Republics in the former Spanish colonies that led to the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 is one of Traub’s best.

Adams’ journal contains copious details of negotiations, social observations, and acute analysis. Adams’ mindset, particularly as it related to the intellectual underpinnings of his foreign policy is incisive. What emerges is a man whose belief system is somewhere between a realist and an idealist who spent his entire career trying to enhance American prestige and territory while avoiding what he considered reckless adventures, i.e.; recognition of Spanish Republics, whether to invade Cuba, the seizure of West Florida among others. The intellectual core of Adams’ belief system rested on “the crucial distinction he made between freedom as a donation or grant from a sovereign and freedom as an act of mutual acknowledgement among equals. This was America’s gift to mankind—a gift [that Adams] hoped to spread across the globe.”

(Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States and a political foil to John Quincy)

Traub correctly points out that Adams’ was not a politician and would not seek office and do the necessary lobbying and cajoling to gain support for his own candidacy, and after assuming the presidency, to gain support for his legislative goals, particularly that of internal improvement and creating an infrastructure linking the expanding country. The machinations involving the 1824 and 1828 presidential elections, his relationship with men like Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Andrew Jackson, and especially his term as president can best summed up by the British historian George Dangerfield, here was “a rather conspicuous example of a great man in the wrong place, at the wrong time with the right motives and a tragic inability to make himself understood.”

Adams’ later career is presented in a clear and concise manner as he enters the House of Representatives, the only president to do so. For Adams the issue of slavery was paramount and he saw the problem of states’ rights over tariffs as nothing more than a cover for the “peculiar institution.” In the 1840s Adams found himself in the midst of many heated debates dealing with slavery. At times he refused to label himself as an abolitionist, and would argue before the Supreme Court representing the men who had seized the slave ship, Amistad. Further, he would become a thorn in the side of states’ rights supporters of slavery in the House of Representatives by repeatedly arguing against the “gag rule,” introducing petitions against slavery, and defending himself as attempts to censure him for his opposition to the “slavocracy” were introduced. Adams would become a man without a party as he would support no faction in the House and found a unique role for himself, “the solitary vote of conscience.”

John Quincy Adams was the last link to the founding generation which in part makes his life so important. In addition, he is also the last link between the creation of the United States and its near destruction by Civil War. In a sense Traub argues that Adams’ time in the oval office was an unsuccessful interlude in a remarkable career that saw principle over expediency as the guiding light of one of the most remarkable figures in American history. For Adams, no matter what the situation, Washington’s message in his Farewell Address to remain neutral abroad, achieve unity at home, and create the consolidation of the continent were his guiding principles and Traub does an excellent job explaining how his subject went about trying to achieve them.

(John Quincy Adams, the sixth president of the United States)