For members of my generation the name Henry Kissinger produces a number of reactions. First and foremost is his “ego,” which based on his career in public service, academia, and his role as a dominant political and social figure makes him a very consequential figure in American diplomatic history. Second, he fosters extreme responses whether your views are negative seeing him as a power hungry practitioner of Bismarckian realpolitik who would do anything from wiretapping his staff to the 1972 Christmas bombing of North Vietnam; or positive as in the case of “shuttle diplomacy” to bring about disengagement agreements between Israel and Egypt, and Israel and Syria following the 1973 Yom Kippur War and the use of linkage or triangular diplomacy pitting China and the Soviet Union against each other. No matter one’s opinion Thomas A. Schwartz’s new book, HENRY KISSINGER AND AMERICAN POWER: A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY, though not a complete biography, offers a deep dive into Kissinger’s background and diplomatic career which will benefit those interested in the former Secretary of State’s impact on American history.

Schwartz tries to present a balanced account as his goal is to reintroduce Kissinger to the American people. He does not engage in every claim and accusation leveled at his subject, nor does he accept the idea that he was the greatest statesman of the 20th century. Schwartz wrote the book for his students attempting to “explain who Henry Kissinger was, what he thought, what he did, and why it matters.” Schwartz presents a flawed individual who was brilliant and who thought seriously and developed important insights into the major foreign policy issues of his time. The narrative shows a person who was prone to deception and intrigue, a superb bureaucratic infighter, and was able to ingratiate himself with President Richard Nixon through praise as his source of power. Kissinger was a genius at self-promotion and became a larger than life figure.

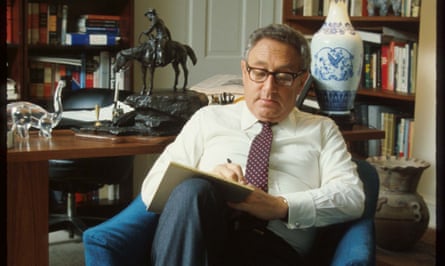

(Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon)

According to Schwartz most books on Kissinger highlight his role as a foreign policy intellectual who advocated realpolitik for American foreign policy, eschewing moral considerations or democratic ideas as he promoted a “cold-blooded” approach designed to protect American security interests. Schwartz argues this is not incorrect, but it does not present a complete picture. “To fully understand Henry Kissinger, it is important to see him as a political actor, a politician, and a man who understood that American foreign policy is fundamentally shaped and determined by the struggles and battles of American domestic politics.” In explaining his meteoric rise to power, it must be seen in the context of global developments which were interwoven in his life; the rise of Nazism, World War II, the Holocaust, and the Cold War.

In developing Kissinger’s life before he rose to power Schwartz relies heavily on Niall Ferguson’s biography as he describes the Kissinger families escape from Nazi Germany. Schwartz does not engage in psycho-babble, but he is correct in pointing out how Kissinger’s early years helped form his legendary insecurity, paranoia, and extreme sensitivity to criticism. In this penetrating study Schwartz effectively navigates Kissinger’s immigration to the United States, service in the military, his early academic career highlighting important personalities, particularly Nelson Rockefeller, and issues that impacted him, particularly his intellectual development highlighting his publications which foreshadowed his later career on the diplomatic stage. However, the most important components of the narrative involve Kissinger’s role in the Nixon administration as National Security advisor and Secretary of State. Kissinger was a practitioner of always keeping “a foot in both camps” no matter the issue. As Schwartz correctly states, “Kissinger sought to cultivate an image of being more dovish than he really was, and he could never quite give up his attempts to convince his critics.” He had a propensity to fawn over Nixon and stress his conservative bonafede’s at the same time trying to maintain his position in liberal circles. Though Schwartz repeatedly refers to Kissinger’s ego and duplicitousness, he always seems to have an excuse for Kissinger’s actions which he integrates into his analysis.

Schwartz correctly points out that Nixon’s goal was to replicate President Eisenhower’s success in ending the Korean War by ending the war in Vietnam which would allow him to reassert leadership in Europe as Eisenhower had done by organizing NATO. This would also quell the anti-war movement in much the same way as Eisenhower helped bring about the end of McCarthyism. Schwartz offers the right mix of historical detail and analysis. Useful examples include his narration of how Nixon and Kissinger used “the mad man theory” to pressure the Soviet Union by bombing Cambodia and North Vietnam; the employment of “linkage” to achieve Détente, SALT I; and ending the war in Vietnam by achieving a “decent interval” so Washington could not be blamed for abandoning its ally in South Vietnam; and bringing about cease fire agreements following the 1973 Yom Kippur War. In all instances Kissinger was careful to promote his image, but at the same time play up to Nixon, the man who created his role and allowed him to pursue their partnership until Watergate, when “Super K” became the major asset of the Nixon administration.

Kissinger was the consummate courtier recognizing Nixon’s need for praise which he would offer after speeches and interviews. Kissinger worked to ingratiate himself with Nixon who soon became extremely jealous of his popularity. The two men had an overly complex relationship. It is fair to argue that at various times each was dependent upon the other. Nixon needed Kissinger’s popularity with the media and reinforcement of his ideas and hatreds. Kissinger needed Nixon as validation for his powerful position as a policy maker and a vehicle to escape academia. Schwartz provides examples of how Kissinger manipulated Nixon from repeated threats to resign particularly following the war scare between Pakistan and India in 1971, negotiations with the Soviet Union, and the Paris Peace talks. Nixon did contemplate firing Kissinger on occasion, especially when Oriana Fallaci described Kissinger as “Nixon’s mental wet nurse” in an article but realized how indispensable he was. What drew them together was their secret conspiratorial approach to diplomacy and the desire to push the State Department into the background and conduct foreign policy from inside the White House. Schwartz reinforces the idea that Kissinger was Nixon’s creation, and an extension of his authority and political power as President which basically sums up their relationship.

Schwartz details the diplomatic machinations that led to “peace is at hand” in Vietnam, the Middle East, and the trifecta of 1972 that included Détente and the opening with China. Schwartz’s writing is clear and concise and offers a blend of factual information, analysis, interesting anecdotes, and superior knowledge of source material which he puts to good use. Apart from Vietnam, the Soviet Union, and the Middle East successes Schwartz chides Kissinger for failing to promote human rights and for aligning the United states with dictators and a host of unsavory regimes, i.e.; the Shah of Iran, Pinochet in Chile, and the apartheid regimes in Rhodesia and South Africa. Schwartz also criticizes Kissinger’s wiretapping of his NSC staff, actions that Kissinger has danced around in all of his writings.

Though most of the monograph involves the Nixon administration, Schwartz explores Kissinger’s role under Gerald Ford and his post-public career, a career that was very productive as he continued to serve on various government commissions under different administrations, built a thriving consulting firm that advised politicians and corporations making him enormous sums of money, and publishing major works that include his 3 volume memoir and an excellent study entitled DIPLOMACY a masterful tour of history’s greatest practitioners of foreign policy. Kissinger would go on to influence American foreign policy well into his nineties and his policies continue to be debated in academic circles, government offices, and anywhere foreign policy decision-making is seen as meaningful.

After reading Schwartz’s work my own view of Kissinger is that he is patriotic American but committed a number of crimes be it domestically or in the international sphere. He remains a flawed public servant whose impact on the history of the 20th century whether one is a detractor or promoter cannot be denied. How Schwartz’s effort stacks up to the myriad of books on Kissinger is up to the reader, but one cannot deny that the book is an important contribution to the growing list of monographs that seek to dissect and understand “Super-K’s” career.

(1939 World’s Fair, New York City)

(1939 World’s Fair, New York City)