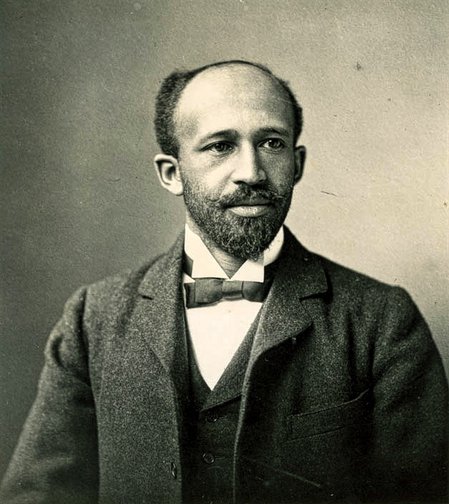

(W.E.B. Du Bois)

W.E.B Du Bois devoted his life’s work to achieving equal citizenship for all African Americans. He worked tirelessly to achieve his goals after becoming the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard University and would go on to teach social sciences at Atlanta University, become one of the founders of the NAACP, edited “The Crisis” magazine which was his megaphone to the black community, lectured worldwide, promoted African and West Indian rights against colonial powers, and published a series of thought provoking books. Du Bois was a firm believer that for African Americans to achieve full civil rights and political representation they would have to be led by a black intellectual elite – the key being advanced education that would lead to leadership. He targeted racism, lynchings, Jim Crow laws, and all types of discrimination in his writing and public appearances.

One of the most controversial aspects of his belief system was supporting America’s entrance into World War I, a decision he would come to regret. He argued that if African Americans joined the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in Europe to fight Germany and showed their talent and bravery it would raise their level of acceptance by the American people upon their return resulting in greater rights of freedom and safety. This dream was negated by the reality of American racism , covert and overt violence, and persecution – all conditions consistent with the African American experience throughout American history. Even US Army officials exhibited extreme racism and blatant lies as they erroneously depicted the combat experience of African American troops in Europe.

To atone for this grievous error in judgement, Du Bois wanted to set the historical record straight as World War I did not prove to be the catalyst for equal rights. His strategy centered on a book he would spend nearly two decades entitled, THE BLACK MAN AND THE WOUNDED WORLD. His effort was never completed nor published but it has become the core of an important new monograph by Chad L. Williams, THE WOUNDED WORLD: W.E.B. DUBOIS AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR.

Williams’ book is a comprehensive study of how Du Bois went about achieving his goals. He recounts his battles with the NAACP to obtain funding and support, his battles with fellow historians who he competed with him in trying to produce the definitive study of the war, the role of his ego which did not allow him to accept enough assistance and share the limelight, his writings, particularly in the NAACP magazine, “The Crisis” which he edited, his travels worldwide promoting the Pan African world, and most importantly disseminating his ideas and research a function of his relationship with black veterans of the war, and a firm belief that American racism was destroying black progress, and the colonial European powers imprisoned people of color in a system where they could not achieve progress.

Williams’ approach is a carefully developed thesis supported by numerous excerpts from Du Bois’ writings and commentary buttressed by accounts provided by friends and foes alike, in addition to communications with black veterans and competing historians. Williams fully explores Du Bois’ ideology which rested on his fear that if Germany were victorious in the war its racist government would negatively impact “Black folk” and brown people throughout the world. He knew Germany well having studied at the University of Berlin providing him with firsthand knowledge of the Kaiser’s march toward autocracy, militarism, and empire. He argued that black loyalty to England, France, and Belgium was of the utmost importance despite their colonial records. He believed an allied victory representing democracy was the only acceptable outcome in the war. However, the result of this call to duty was dominated by racism in the military as whites refused to serve with blacks, military leaders refused to allow black officers to command black troops resulting in southern white racist officers treating black soldiers with contempt and at times violence. Williams mentions examples of black officers like Major Charles Young, a graduate of West Point, but being an exceptional soldier did not allow him to fulfill the role Du Bois sought for him and others as the leaders of a new generation of blacks who would gain acceptance from American society.

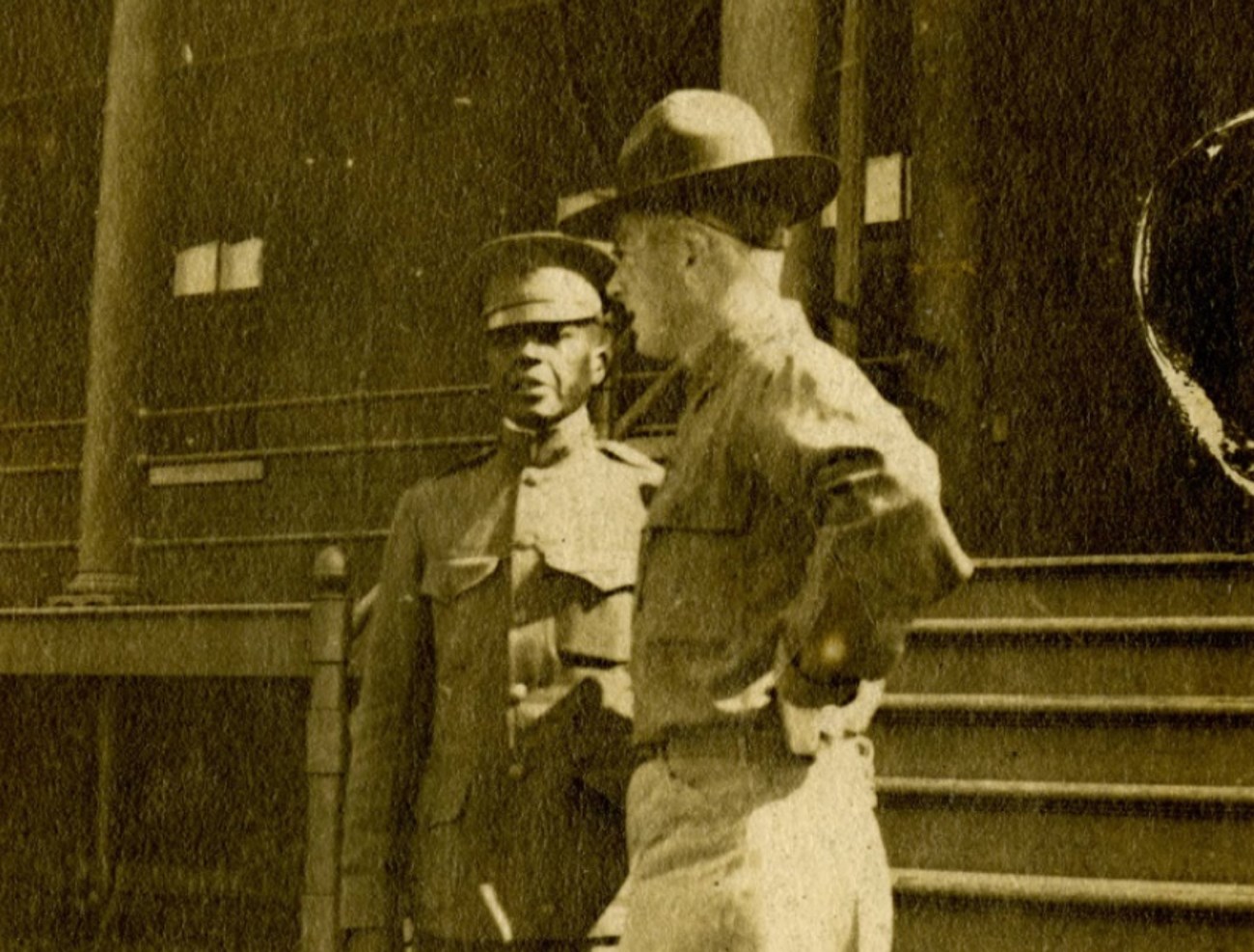

(Over 350,000 African American soldiers served in WWI)

Williams portrays the lies put forth by military authorities when it came to black officers and their service, the performance of the 369th and 92nd divisions of the army, particularly the 368th Infantry Regiment, known as the Harlem Hell fighters, who were assigned to the French Army in April 1918. The Hell fighters saw much action, fighting in the Second Battle of the Marne, as well as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, where black officers were blamed for the slow progress of the offensive with white officers falsely reporting on the performance of thousands of black troops. The treatment of black soldiers carried over into their medical care during and after the war where at first, black doctors and nurses were not allowed to treat black veterans at the new Tuskegee Institute Hospital.

When black veterans returned home they were met with violence and race riots resulting in the deaths of over a thousand people in Tulsa, OK, Chicago, IL, Knoxville, TN, Phillips County, AK, Charleston, SC, and Washington, DC all described in detail by the author. Further with the 1919 Red Scare many blamed black soldiers for bringing communism to America when they returned from Europe. When confronted with the reality of the African American soldier’s experience during their training, the war itself, and the reception they received upon returning from the battlefield, Du Bois committed himself to telling their story.

Williams pulls no punches in presenting Du Bois’ failed odyssey in completing his work. First, he was overwhelmed with materials from his own travels to France to conduct research and influence the Paris Peace Conference. Second, he could never get a handle on the voluminous amounts of material sent to him by black veterans. Third, his intense schedule that saw him work for Pan-African conferences and other causes. Lastly, his other writings, lectures, and as mentioned before his ego which did not allow him to work successfully with others. Further, he distorted his own experiences praising France for using Senegalese troops in the war and their treatment of blacks. All one has to do is examine the French colonial experience to see how wrong he was. Another example is his visit to the Soviet Union in 1926 and for a time believing in the “Marxist wonderland.”

(African-American soldiers (and one of their white officers) of the 369th Infantry, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, practice what they will soon experience, fighting in the trenches of the Western Front)

In the latter part of the narrative Williams explores Du Bois’ life work particularly his realization that his World War I opus would never be completed. The 1920s to 1945 period produced a great deal of success academically with the publication of BLACK RECONSTRUCTION, a widely accepted history of African Americans from 1850 to 1876. In explaining Du Bois’ ideas in his books and other writings Williams traces Du Bois evolution ideologically as he argued that racism and colonization were responsible for two world wars and the failings of democracy pushing him further to the left. As he grew older Du Bois concluded that even after World War II, African Americans were confronted with the same hostility and violence as they did in the post 1918 period. Much to Du Bois’ dismay it was apparent that the arguments he developed for decades pertaining to racism and colonization still applied and he would work assiduously to ameliorate this situation until his death.

Throughout the two decades of preparing the book Du Bois had to overcome his “Close Ranks” editorial from the war supporting the use of African American troops in the war as a vehicle to obtain equality. His decision was wrong, and he would pay a price professionally and personally. Williams describes Du Bois’ effort as his most significant work to never reach the public as he struggled to finish his manuscript and the legacy of the war, however, “By rendering this story in such rich archival detail, Williams’s book is a fitting coda to Du Bois’s unfinished history of Black Americans and the First World War.”*

- Matthew Delmont. “W.E.B. Du Bois and the Legacy – and Betrayal – of Black Soldiers,” New York Times, April 4, 2023.