(John Lewis, third from left, walks with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as they begin the Selma to Montgomery march from Brown’s Chapel Church in Selma on March 21, 1965)

(John Lewis, third from left, walks with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as they begin the Selma to Montgomery march from Brown’s Chapel Church in Selma on March 21, 1965)

If you ever wanted to know what type of man John Lewis was, all you have to do is ask someone from the other side of the political aisle what their opinion is of him. In this case I would point to someone who disagreed with Lewis about every conceivable issue – former North Carolina Congressman and Trump Chief of Staff Mark Meadows who would respond to questions about the Georgia Congressman and Civil Rights leader – “he was my friend,” and Lewis would reciprocate those feelings. You might ask how two such disparate characters could call themselves friends – all you have to do is read Raymond Arsenault’s new biography, JOHN LEWIS: IN SEARCH OF THE BELOVED COMMUNITY to understand the unshakable integrity and believer in man’s humanity which made up the core of the former activist and progressive legislator.

Lewis believed in forgiveness and compassion as part of achieving what referred to as “the beloved community” where racial hatred would be eradicated, and we would all live in a world of fairness and equality as he was determined to replace the horrors of the past and present with his ideals. Arsenault’s biography cannot be described as a hagiography as he delves into Lewis’ life, decisions and actions carefully offering a great deal of praise, but the author does not shy away from his subject’s mistakes and faulty decisions. At a time when racial “dog whistles” dominate a significant element of the political class it is unsettling to listen to a presidential candidate demean his opponent’s racial heritage linking it to her intelligence and background. This has led to racially motivated violent rhetoric that permeates the news making it a useful exercise exploring the life of a civil rights leader who fought valiantly against these elements in our society.

(Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., stands on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., on Feb. 14, 2015. Rep. Lewis was beaten by police on the bridge on “Bloody Sunday” on March 7, 1965, during an attempted march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery)

Arsenault’s monograph begins by exploring Lewis’ rural upbringing in Pike County, Alabama. Sharecropping was the main source of income in a white dominated economic system designed to keep tenant farmers under the thumb of their landlords. Any progress his parents might have achieved was never enough to escape poverty. For Lewis, growing up in this racial and economic system formed a social and intellectual laboratory as he hated working in the cotton fields and soon became intoxicated with education where the inequality of white and black opportunities was glaring. The structure of Jim Crow society dominated. Lewis had high hopes with the Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas but the “massive resistance” the southern white supremacists responded with disabused Lewis that the decision would ameliorate the situation blacks found themselves locked into.

The development of Lewis’ approach to achieving change is explored in detail and we learn the impact of Martin Luther King, Jr. on Lewis at an early age. Arsenault spends a great deal of time delving into the King-Lewis relationship from the mid-1950s civil rights struggles through King’s assassination in April 1968. The development of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) which Lewis would come to lead, and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) is important as it shows the dichotomy that existed in the Civil Rights movement particularly as they split from each other in the early 1960s as Black nationalists like Stokley Carmichael and H. Rap Brown advocated violence against white supremacists took over SNCC.

No matter what aspect of Lewis’ career Arsenault discusses he presents a balanced account offering intimate details whether delving into Lewis remarkable rise within the Civil Rights movements from the late 1950s to 1970; his exceptional organizational skills, the schism that developed and seemed to dominate the movement, his four years on the Atlanta City Council through his congressional career. In recounting Lewis’ decision-making, he relates how each judgement was reached and how it affected his social gospel of the beloved community ideology.

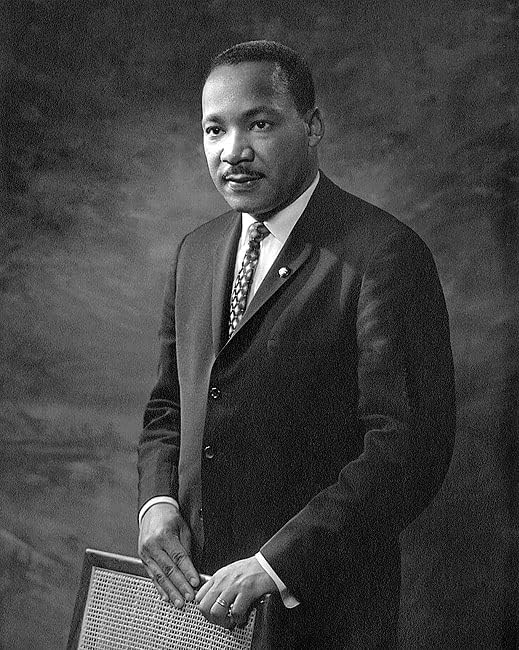

(Martin Luther King, Jr.)

Make no mistake the book is more than an intellectual approach to Lewis’ role in the Civil Rights movement. Arsenault seems to cover all the major aspects of the Civil Rights movement from sit ins, stand ins to boycotts challenging the White supremacist governors, sheriffs and other officials in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee. Places like Selma, Jackson, Montgomery, Memphis come to dominate the narrative as does the impact of peaceful and violent events on Lewis’ belief system and planning.

For Lewis it was a battle to maintain his belief in nonviolent protest as a tool to uplift his community. At times he would become frustrated after he was physically beaten or arrested, but he would always seem to veer away from anything which would contradict his core ideas, even when close friends and other leaders moved away from a total non-violent approach. He grew angry when the younger generation turned to black power and confrontation, but he always remained loyal to his core principles.

Arsenault’s portrayal does reveal a confrontational and antagonistic strain in Lewis’ personality on rare occasions. One that comes to mind is the nastiness of his Georgia congressional campaign against his friend Julian Bond and fellow activist which cost both men a deep friendship when Lewis was victorious.

(Rosa Parks on a Montgomery bus in 1955)

Perhaps Arsenault’s most interesting chapters include Lewis’ evaluation of the Kennedy brothers who came late to the game of protecting civil rights workers. At the outset, Lewis had great hopes for John F. Kennedy, however he would be disappointed as the politics of Southern Democrats got in the way. With the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which the Supreme Court would undermine in 2013, Lewis felt more optimistic, particularly with the metamorphosis of Robert Kennedy, especially after Dr. King was assassinated. There are chapters dealing with the Freedom Riders, important historical figures like Medgar Evers, Emmett Till, Rosa Parks, James Lawson, Andrew Young, Martin Luther King, Jr., James Farmer, Bayard Rustin, along with the Bull Conners, Sheriff Clark, Governors John Patterson and Lester Maddox among many that lend a sense of what it was like to deal with and live through such a tumultuous period in American history.

In the last third of the book, Arsenault describes the Republican resurgence under Gingrich, Reagan and the Bushes which made it difficult for Lewis to navigate the House of Representatives as any liberal agenda was dead on arrival on the House floor. At times he grew upset for the lack of progress that resulted in few if any legislative victories. He had high hopes for the election of Barack Obama, but it was not to be due to Republican obstructionism and in many cases outright racism. The arrival of Donald Trump took his frustration to new levels as events in Charlottesville, Va, a Muslim ban, hideous commentary concerning immigrants, and the actions of Mitch McConnell in the Senate made the achievement of a “beloved community” impossible. Before his death, Lewis would witness a Republican party taking America backwards trying successfully in many cases to undo fifty years of progress made under Democratic leadership – something against which he had repeatedly warned. What separated Lewis from most of his Congressional colleagues was his historical perspective. He could not accept the racism of the Trump administration which returned him to the dark days of the 1960s culminating in the deaths of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy.

(Robert Kennedy’s speech in Indianapolis, IN following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.)

In light of Donald Trump’s racial attacks against Kamala Harris, Lewis’ life story seems apropos in light of where we are as a society and how far, or perhaps not as far we have come after the Civil Rights movement. If there is one area that Arsenault could have explored more was learning about the people who knew Lewis the longest and what these relationships actually meant to him. However, Arsenault’s book is well written, researched based on documents and interviews, and has produced a thoughtful and measured account of Lewis’ life and work which continued even as he contracted pancreatic cancer and worked until ten days before his death in 2020 as he visited Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, DC.

(Tear gas fills the air as state troopers, on orders from Gov. George Wallace, break up a march in Selma on March 7, 1965, on what is known as “Bloody Sunday”)

(Tear gas fills the air as state troopers, on orders from Gov. George Wallace, break up a march in Selma on March 7, 1965, on what is known as “Bloody Sunday”)