(On 30 April 1980 six gunmen took over the Iranian embassy in Kensington. The siege ended when the SAS stormed the building.)

(On 30 April 1980 six gunmen took over the Iranian embassy in Kensington. The siege ended when the SAS stormed the building.)

If one thinks about events that took place in 1980 two hostage situations should come to mind. The first and more prominent was the seizure of the American Embassy in Tehran by Islamic radicals imprisoning 52 Americans for over a year. The second took place in London months later as Iranian Arabists seized the Iranian embassy and took 26 hostages for six days until they were freed. The first event in Tehran took place following the overthrow of the Pahlavi Dynasty as part of the Islamic Revolution that brought Ayatollah Khomeini to power who instituted an extreme Islamic regime. The hostage crisis was very impactful for the 1980 Presidential election as President Jimmy Carter’s failure to bring home the hostages, despite a valiant rescue attempt that failed, contributed greatly to his defeat by Ronald Reagan. Meanwhile across the Atlantic, the lesser known hostage situation was evolving as six heavily armed gunmen stormed the Iranian Embassy as a means of gaining support against the new Iranian government who were persecuting the Iranian Arab ethnic minority in Khuzestan, Iran.

Both crises produced rescue missions, the first by the United States, Operation Eagle Claw approved by President Carter failed as technical difficulties resulted in a disaster in the Iranian desert. The second was conducted by British Special Forces (SAS) and was deemed successful. Many accounts of the American hostage crisis and failed rescue mission have been written, but until now the accounts of events in London have remained largely negligible. The narrative description, analysis, and character studies associated with the London crisis has been filled by Ben Macintyre’s latest effort; THE SIEGE: A SIX DAY HOSTAGE CRISIS AND THE DARING SPECIAL FORCES OPERATION THAT SHOCKED THE WORLD.

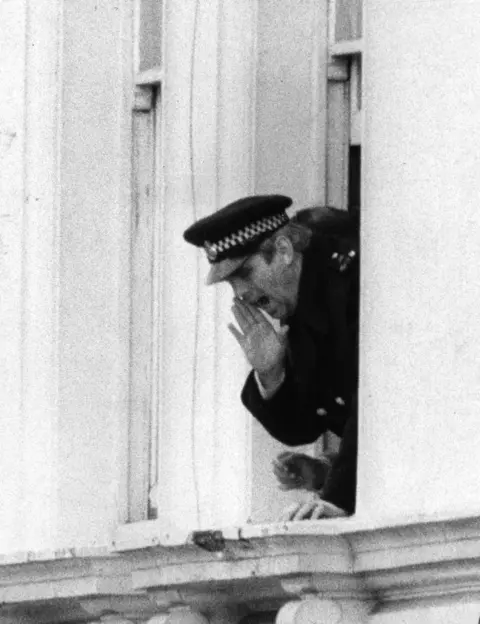

(One of the 26 hostages was PC Trevor Lock, of the diplomatic protection squad, who was standing guard outside the embassy. He can be seen here talking with police negotiators from an upstairs window.)

(One of the 26 hostages was PC Trevor Lock, of the diplomatic protection squad, who was standing guard outside the embassy. He can be seen here talking with police negotiators from an upstairs window.)

Macintyre’s new book is his latest success after having written more than a dozen acclaimed books about war and espionage, including volumes on British Spy Kim Philby, the Nazi POW camp Colditz, the preparations for D-Day, and an account describing how Oleg Gordievsky the Russian spy helped bring the Cold War to a conclusion. As is the case with all of his books, Macintyre latest is highlighted by a taut and engrossing story that is deeply researched that will draw in the reader’s attention as it seems to flow like a novel, but in reality is a work of historical non-fiction. For Macintyre, the key to the narrative is that “no one knows how they will respond to lethal jeopardy, until they have to.”

Macintyre comes to a number of important conclusions as he develops his monograph. He sees the crisis as a turning point in the relationship between breaking news and the viewing public as he describes how media outlets responded to the hostage situation. Second he argues that this was a pivotal moment in the public history of Britain’s secretive SAS (Special Air Service). Lastly, it was an early test for the new government of Margaret Thatcher, whose response to the crisis would reaffirm her reputation as the “Iron Lady.”

The seizure of the embassy stemmed from the treatment of the Arab minority in Iran under the reign of the Shah as well as the Khomeini government. Originally when the Islamic Republic was founded it promised to recognize Arabistan’s autonomy and the rights of its people. Almost immediately it changed its approach and clamped down on its Arab population just as the Shah had as oil rich Khuzestan drove policy. Further complicating the situation was the role of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein who saw an opportunity to exacerbate relations with the new Iranian regime and take advantage of the situation as he saw Iran’s aggressive new theocracy as a threat to his power and ambitions. Khuzestan was an easy and cheap way to undermine the Khomeini regime and destabilize Iran.

Macintyre clearly explains the demands of the hostage takers – their motivations, and how their actions had major implications for the Middle East. When Republican Guards engaged in violence and death against Arab demonstrators it spurred on a small group led by Towfiq Ibrahim al-Rashidi, also referred to as Salim whose brother was tortured and executed by Republican Guards.

(The SAS went in barely 20 minutes after the command was issued – their assault relayed by TV cameras trained on the embassy. In 15 minutes it was all over.)

(The SAS went in barely 20 minutes after the command was issued – their assault relayed by TV cameras trained on the embassy. In 15 minutes it was all over.)

Throughout the narrative Macintyre integrates the ongoing American crisis in Tehran stressing the Thatcher government’s concerns after the American rescue attempt to free its hostages was a failure – she would refuse to provide victory for the Khomeini regime at any cost. There was no way she would allow the terrorists to walk free. Macintyre also stresses the mindset of the hostages. Their fears are paramount, but the author also describes how Stockholm and Lima syndrome emerge amongst the hostages as some developed a certain empathy for the terrorist’s themselves. The strategies pursued by government negotiators is on full display as is SAS planning for any eventuality during the crisis.

Interestingly Towfiq and his cohorts were not trained terrorists as improvisation best describes their behavior as their strategy did not play out as they had hoped. Their behavior during the crisis was not consistent, particularly Towfiq who was hard to read. Sometimes calm, but at the next “moment polite and apologetic, then suddenly aggressive; in one breadth threatening to kill many innocent people, and in the next describing himself as a benevolent humanitarian.”

There are many important characters that emerge throughout. Obviously Towfiq and his accomplices, but others stand out. John Albert Dillon, the chief troubleshooter for Scotland Yard; Fred Luff the main government negotiator; Chris Cramer, a BBC producer, Simeon Harris, a BBC sound engineer, and Major Hector Gullen; the Commander of B Squadron – the standing counter-terrorist force; Professor Peter Gunn, a psychiatrist at Maudsley Psychiatric Hospital and a leading authority on the terrorist mind; and a number of other government officials and personalities. Among the hostage’s Syrian journalist Mustapha Karkouti stands out as does Seyyed Abbas Lauasani, the Republican Guard spy who served in the embassy; Dr. Gholam-Ali Afrouz, the Iranian ambassador to Britain; Roya Kaghachi , the secretary to the ambassador; Trevor James Lock, the police constable who guarded the embassy; and Ron Morris, the embassy majordomo. Macintyre provides brief biographical sketches of all the main participants and the reader acquires intimate knowledge of their backgrounds which impact their behavior during the crisis.

(Elite members of Britain’s SAS abseil down the wall at the rear of the embassy on May 5, 1980, to end the six-day siege.)

In his Washington Post review Charles Arrowsmith points out that “Macintyre’s many sources include the diaries of hostages as well as interviews he conducted with SAS officers who participated in the event — the first such interviews to be sanctioned by the British Defense Ministry. He consulted other living witnesses, including Trevor Lock, the police officer who was guarding the embassy, and Maj. Hector Gullan, who coordinated the SAS raid. Fowzi Badavi Nejad, the only terrorist not killed in the raid, is alive, too — he’s still in Britain, released from prison in 2008 and living under an assumed name — though it’s not clear if he spoke to Macintyre. Regardless, the final product of Macintyre’s research is a remarkably immersive account of what happened.

THE SIEGE is brilliantly assembled. Despite the historic import of its events, it’s the humdrum details that linger: an order of 25 hamburgers for those trapped inside the embassy; armed SAS officers gathered around a TV to watch the snooker; a captive engrossed in Frederick Forsyth’s espionage classic “The Day of the Jackal.” For policeman Trevor Lock, it’s the scent of Old Spice, a bottle of which the terrorists found during their time in the embassy, that takes him right back to the scene. It contains the faint but ineradicable trace of an event whose significance persists for both him and the world, even as its particulars have faded. Macintyre’s superb reconstruction restores it to vivid, complex life.”**

**Charles Arrowsmith, “Ben Macintyre’s THE SIEGE vividly recounts a hostage crisis,” Washington Post, September 20, 2024.

(On the sixth day of the siege, after the gunmen shot dead Iranian press attache Abbas Lavasani and dumped his body outside the building, Home Secretary William Whitelaw ordered the SAS to attack.)

(On the sixth day of the siege, after the gunmen shot dead Iranian press attache Abbas Lavasani and dumped his body outside the building, Home Secretary William Whitelaw ordered the SAS to attack.)