(The Strand Book Store, 12th and Broadway, NYC)

When I first graduated from college in 1971 I worked at a small family owned publishing firm in lower Manhattan called T.Y. Crowell and Company. It introduced me to the process of book publishing and afforded me enough of a salary that every Friday when I was paid I would walk to Broadway and 12th Street in Manhattan, the home of the Strandbook store. I would proceed to blow half my paycheck on remaindered/used books and have a falafel sandwich from the food truck in front of the store. This behavior continued for about a year when Crowell was sold to Dunn and Bradstreet and moved the firm to 666 Fifth Avenue (the building the Saudis bailed out Jarad Kushner with $2 billion!) and the doom of sleaze of corporate America. This led to my resignation when the office manager, affectionately labeled by my boss as “silly bitch” refused to allow me to hang my Bob Dylan poster on the wall. I proceeded to graduate school to earn a Ph. D in history.

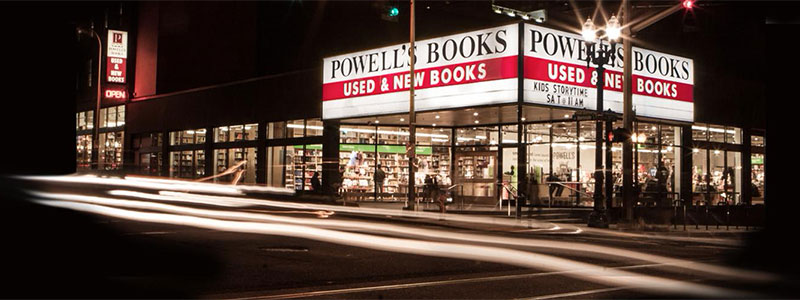

The thing I carried with me from this experience was my love of books. Today I own a library of about 8500 volumes which has created a family problem when trying to downsize. Over the decades I have spent an inordinate amount of time browsing and buying in bookshops. The Strand, despite its commercialization since COVID remains my favorite. As my wife and I have traveled across Europe and other places I make it a habit to visit a bookstore and purchase a book in every city visited. Perhaps my favorite is Bertrand Bookstore located in Lisbon, Portugal, supposedly the oldest book establishment in Europe. Strolling on Charing Cross Street in London also produces many bookshops which I have fond memories of. In the United States among my favorites include Powell Books in Portland and Chicago; Haslams Books in St. Petersburg, Titcomb’s Books in East Sandwich located on Cape Cod, the Harvard Bookstore in Cambridge, MA, Water Street Books in Exeter, NH, Douglas Harding Rare Books in Wells, ME, Old Number 6 Book Depot in Henniker, NH, Toadstool Bookstore in Peterborough, NH, and of course there are numerous others that I could list!

(Powell’s Bookstore, Portland, OR)

As I have spent so much time in bookshops I have developed a love for the ambiance, smell, and contact with other book buyers who share my affliction as a book-a-holic as I cannot leave a bookshop without a purchase. Over the years I have looked for the best history of American bookstores. Recently, I believe I have found it, Evan Friss’ latest endeavor, THE BOOKSHOP: A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN BOOKSTORE.

Friss has authored an ode or perhaps a love song to his subject – a warm historical recounting of the personalities, challenges, historical perspective, and pleasure people derive from frequenting these establishments. Friss introduces his topic by describing a small bookshop located in New York City’s West Village which opened in the 1970s. This marked his entrance into the wonderful world of books that I have loved since my early teenage years.

Over the years independent bookstores have been disappearing. According to Friss, in 1993 there were 13,499 bookstores in America, in 2021 just 5,591. Friss is correct in that, “if bookstores were animals, they’d be on the list of endangered species.”

(Books are Magic Bookstore in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, NY owned by author Emily Staub and her husband)

Friss lays out his monograph in chapters set in a series of book establishments that includes itinerant book people who used carriages pulled by horses in the 18th century onward, trucks filled with books, kiosks on streets, book delivery trucks (long before Amazon), and of course a brick and mortar shops. These establishments produced amazing personalities that include Toby, the owner of Three Lives Bookstore, located in the West Village; Benjamin Franklin’s Bookshop in Philadelphia in the 1770s, Old Corner Books run by B. H. Ticknor, a friend of Nathaniel Hawthorne; George Harrison Mifflin and E.P. Dutton who also owned bookshops during this period; James T. Fields who also published The Atlantic Monthly, Marcella Hahner who supervised Marshall Field’s Department store large book section and greatly impacted the role of women as book sellers through book fairs, author presentations (i.e.; Carl Sandburg’s books on Lincoln), she could make a book’s success if she endorsed and ordered it – a 1920s Oprah!; Roger Mifflin who drove a truck selling books, as did Helen McGill. Frances Steloff developed the Gotham Book Mart that specialized in literature that dominated the New York book scene including publishing for decades including World War II. Ann Patchett, bestselling author opened Parnassus Books in Nashville, as the city was losing bookshops and she believed with her partner Karen Hayes that the city needed an indie bookstore that thrived as she saw herself protecting an endangered species. Lesley Stahl called Patchett “the patron saint of independent bookstores.” Lastly, how could you author a book about bookshops and not provide a mini biography of Jeff Bezos and how Amazon tried to take over the book trade.

Friss is correct that when entering a bookstore, it is a “sensory experience” – The scent of a book known as “bibliosmia” which I love while holding a book cannot be replicated with a Kindle. These experiences have been greatly impacted through our sectionalist history. Since most books published in the United States before the Civil War were in the northeast, authors have to avoid any discussion of slavery for fear of lost sales below the Mason-Dixon line. This did not stop Tickner and Fields from publishing UNCLE TOM’S CABIN. Soon Ticknor was taken over by E.P. Hutton and merged with Houghton, Mifflin.

- (Water Street Books, Exeter, NH)

The role of book buyers is carefully laid out by the author. It is in this context that Paul Yamazaki is discussed and his San Francisco bookshop It was during the late 19th century that traveling bookstores emerged from Cape Cod to Kennebunkport, Northport to Middlebury, all the way to Lake Placid. They would drive their carts, carriages, trucks all over making customers and friends. Yamazaki would order appropriate books and deliver them to his customers – especially important in rural areas.

Friss uncovers many tantalizing stories about the book business, particularly the relationships between booksellers and the evolution of how these interactions would later lead to the forming of publishing companies that set the market with book buyers of what was available for the public to read and purchase. Perhaps the best stories are presented in his chapter on The Strand Bookshop as it brought me back to 1971 and browsing their stacks. The picture of the shop that Friss includes from the 1970s is exactly as I remember it.. The narrowness of the aisles, the smell of used books, and the store’s ambiance were perfect. For me going downstairs where the 50% off publisher copies is located was my favorite. Friss includes personality studies of Burt Britton and Benjamin Bass who owned and operated Strand for years. Friss’ focus is on the evolution of the Strand from its 4th avenue Book Row location to 12th and Broadway. Due to Covid and Amazon the shop went under a more commercial transformation (it now offers pastries and “Strand blend coffee”) but it remains an iconic bookshop and tourist attraction, but it has lost some of its roots from the 1960s and 70s.

Friss correctly points out that bookshops had a significant role in American foreign policy aside from its domestic influence. The Aryan Book store opened in Los Angeles in 1933 and evolved into the center of American Nazism managed by Paul Themlitz. Book shops were also caught up in the anti-communist movement with over 100 stores run by the Communist Party of the United States. Wayne Garland managed a successful socialist bookstore in Manhattan called the Worker’s Bookshop and also fought against Fransico Franco in the Spanish Civil War as part of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. Congress even held hearings in the 1930s about these stores, particularly the growing communist movement. This would lead to further issues during the McCarthy period in the early 1950s as government officials believed that if you frequented certain types of bookstores it was an indicator of your politics and threat level. Apart from the right components of the book trade Fliss nicely integrates the other spectrum, recounting counterculture shops.

(Author and ownerof Parnassus Books in Nashville, TN, Ann Patchett)

Fliss doesn’t miss any angle when presenting his history of bookshops as he discusses the life of Craig Rodwell who was known as the “sage of gay bookselling.” Rodewell would open the Oscar Wilde Bookshop in Greenwich Village in 1967 with the store serving as the front line of activism after the NYPD launched the Stonewall Raid which would lead to the gay pride movement. All of these types of bookshops are important to American culture which today is under attack as more and more state legislatures are producing legislation to ban books. Interestingly, freedom of speech does not seem to be part of the right wing interpretation of the constitution.

One of the most interesting aspects of Fliss’ research is the impact of the killing of George Floyd on the book market. As the “Black Lives Matter” movement spread the increase in book sales to black owned bookshops skyrocketed. Fliss provides a concise history of black owned bookshops dating back to the 19th century and his conclusions are quite thoughtful.

Fliss devotes the last section to the growth of large chain bookstores like B. Dalton, Borders, Waldenbooks, Doubleday, and the goliath of stores created by Barnes and Noble. By 1997 Barnes and Noble and Borders accounted for 43.3% of all bookstore sales. By 2007 Barnes and Noble had $4.65 billion in book sales and the competition was slowly withering away. Fliss explains that 2019 what once was a battle between indie bookstores and the large chains evolved into a war between in-person bookstores and Amazon. Barnes and Noble’s massive growth had stalled, and an investor group controlled by Waterstones, Britain’s largest bookstore chain, poured money into Barnes and Noble, who like others had significant issues caused by Covid. Its resurgence in its fight with Amazon was led by James Daunt, known as a “bookstore whisperer” in England – his goal was to make Barnes and Noble more like an independent store. Daunt has been very successful in recreating Barnes and Noble and Fliss correctly concludes that the fate of the chain is “intertwined with the fate of American bookselling and maybe even the fate of reading itself” as Amazon is always hovering over what we read and where we buy.

Fliss has authored a phenomenal book tracing the development of bookshops for centuries culminating with the threat of Amazon and Jef Bezos who wanted to put “anyone selling physical books out of a job.” The situation grew worse with the Kindle resulting in 43% of indie shops being driven out of business and by 2015 with its $100 billion in books sales. By 2019 Amazon sold 50% of the books purchased in the United states. What is clear from Fliss’ somewhat personal monograph, bookstores were a public good – the benefit was the experience – the browse, interaction with others, a place of comfort and rejuvenation. Fliss’ work is a treasure for anyone who loves books, and possibly for those who don’t!

(The Strand Bookstore)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/John-C-Fremont-3000-3x2gty-56a489c65f9b58b7d0d770e1.jpg)

![[BLANK]](https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/media/collectiveaccess/images/1/4/81752_ca_object_representations_media_1482_large.jpg)