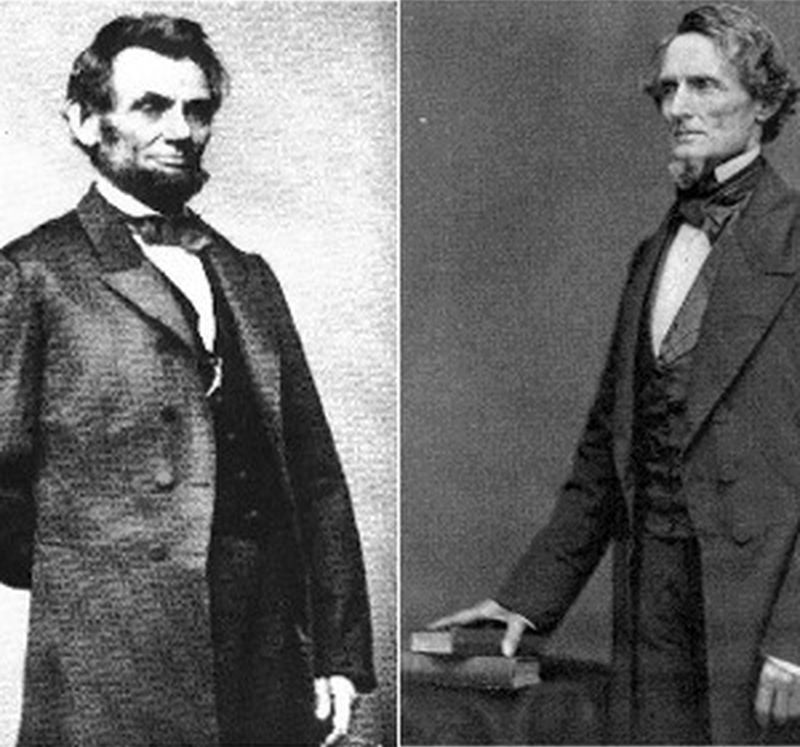

(Confederate President Jefferson Davis and President Abraham Lincoln)

One might ask if we need another book about the Civil War. What angle might an author take that would appear new and consequential? It appears that presidential historian Nigel Hamilton, the author of a trilogy focusing on the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, another on Bill Clinton, and finally one on John F. Kennedy has done so. Further, Hamilton has also written a monumental multi-volume biography of British General Bernard “Monty” Montogomery and seems to have found his Civil War niche. Hamilton’s latest effort entitled THE WAR OF PRESIDENTS: LINCOLN VS. DAVIS focuses on presenting a comparative biography of Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis zeroing in on the first two years of the war and their viewpoints and actions. Hamilton’s goal as he states in the preface is “to get into their warring minds and hearts – hopefully supplying enough context, meanwhile : to judge their actions and decisions, both at the time and in retrospect.”

From the outset Hamilton raises an important question; how did the “rail-splitter” from Illinois grow into his critical role as Commander-in-Chief, and manage to outwit his formidable opponent, Jefferson Davis who was a trained soldier and Mexican War hero, while Lincoln, a country lawyer had served only briefly in the militia? The answer to this question is fully addressed by the author as he reaches a number of important conclusions, none more important than Lincoln’s refusal to name slavery as a cause and goal for the war in order to maintain border state loyalty and encourage a reunion with the Confederacy. This was Lincoln’s mindset for two years as Hamilton relates his personal moral equation in dealing with slavery as he ultimately will change his policy and issue the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 freeing 3.5 million slaves without which the south could not fund their armed insurrection. Once Lincoln made it clear the war was being fought over slavery European support for the south and diplomatic recognition necessary for the survival of the Confederacy would not be forthcoming – sealing the defeat of the south and the failure of Davis’s presidency.

(Secretary of State William Henry Seward)

Hamilton’s methodology is to alternate chapters following the lives of both men. From Davis’s arrival in the first Confederate capital in Montgomery, Alabama to Lincoln’s tortuous voyage avoiding assassination plots as he arrived in Washington, DC. The key topics that Hamilton explores include a comparison of each president’s personality, and his political and moral beliefs including events, strategies, and individuals who played a significant role leading up to and the seizure of Fort Sumter. These figures encompass role of Major Robert Anderson who commanded the fort and General Winfield Scott, who headed northern forces, the role of Lincoln’s cabinet particularly Secretary of State William H. Seward, who was seen by some as committing treason for his actions, Postmaster General Montogomery Blair who was against the war, and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Hamilton goes on to lay out the catastrophe that was General George McClellan and his paranoia and refusal to take advantage of his overwhelming military resources and his incompetent “Peninsula Campaign.”

Hamilton does a wonderful job digging into the personalities of the major historical figures and how their actions influenced Lincoln and Davis and the course of the war. The roles of McClellan, Fremont, Scott have been mentioned but the author also delves into the mindset of important military leaders such as Generals Joe Johnston, Pierre Beauregard, Stonewall Jackson, Irvin McDowell, and others. Further, Hamilton also introduces a number of important sources that other historians have not mined as carefully. For example, the diaries of State Department translator Count Adam Gorowski, a Polish aristocrat whose negative opinions of Lincoln are striking as it seemed Lincoln was unable to enforce the powers of his office and lack of military competence would have drastic consequences. London Times war correspondent William Howard Russell’s opinions are explored in detail, in an addition to Elizabeth Keckley, a formerly enslaved woman who first served as a seamstress to Davis’s wife Varina, and later to Mary Todd Lincoln, and John Beauchamp Jones, a War Department clerk from Maryland who supported the Confederacy.

(Commander of Northern forces, General George Brinton McClellan)

Hamilton’s view of Lincoln is rather negative for the first two years of the war as he writes, Lincoln, “had really no idea what he must do to win the war – or how to reconstruct a civil society in the slaveholding south, so dependent upon cotton, if he ever did.” Interestingly, Davis wanted a defensive war to protect the deep south, he never favored a full blown civil war with the seizure of Washington, but was forced into it when more states seceded, he was called upon to protect them as they moved the Confederate capital to Richmond, Va. Davis’ strategy was to bluff Lincoln until it was clear that McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign was foolish, then he went on the offensive.

What sets Hamilton’s work apart from others is his writing style. His narrative prose flows evenly and makes for a comfortable read. His sourcing is excellent adding the latest documents and secondary sources available. His integration of letters, diary excerpts, and other materials creates an atmosphere where the reader is party to conversations and actions between the main characters, i.e., Lincoln-McClellan interaction in person and in writing among many others. Hamilton’s approach provides for subtle analysis, but he does not hold back, particularly in providing evidence for Lincoln’s mediocre performance as a military leader, who is overly worried about political issues. This is evident in his approach to McClellan’s Peninsula campaign when the overland option driving south toward Richmond made much more sense than a complex amphibious strategy designed to go ashore in southern Virginia and drive north toward the Confederate capital. By 1861 Hamilton argues that Lincoln seemed out of his depth as a military commander and appeared reluctant to make military decisions. His reaction to John C. Fremont’s Emancipation Proclamation in Missouri is a case in point as he forced the General to rescind the order which was consistent with his refusal to have the issue of slavery affect the fighting.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/John-C-Fremont-3000-3x2gty-56a489c65f9b58b7d0d770e1.jpg)

(John C. Fremont- “The Pathfinder”)

Davis’ strategy was a simple one. Fight a defensive war and gain European recognition for the Confederacy. His problem was slavery was viewed negatively in European diplomatic circles. Davis hoped that the need for cotton, necessitating England and France breaking through the northern blockade, would become more important than moral stances related to the enslavement of three and half million people.

Lincoln had difficulty accepting the fact it was slavery that allowed the Confederacy to fight as cotton provided the wealth to purchase weapons, slaves provided food to survive, and the overall manpower to run plantations when southern whites went off to fight. Davis was fully aware of Confederate weaknesses; southern planters were against taxation, European recognition was not forthcoming, 5.5 million v. 23 million people, the extra expense and manpower to defend Kentucky and Virginia spreading his lines thinner and thinner until McClellan’s refusal to engage with superior forces provided Davis with a solution.

Perhaps Hamilton’s most important theme is “Lincoln’s eventual recognition in extremis, of his blunder would compel him, belatedly, to change his mind and agree to make the Confederacy’s use of millions of enslaved Black people – almost half the Southern population – a war issue.” By doing so Lincoln poked holes through Davis’s southern fiction that the Confederacy had “a legal justification for mounting armed insurrection: defense of soil and family.”

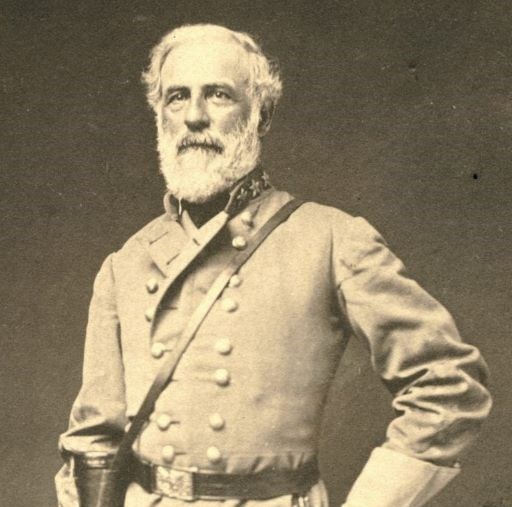

(General Robert E. Lee, pictured here in 1863, never wore the Confederate uniform in this house. Three days after his resignation from the US Army, he was appointed commander in chief of Virginia’s military)

Hamilton argues that Davis did not defeat Lincoln because of hubris in the person of General Robert E. Lee who took Confederate troops north in 1862, and Davis’s failure to stop him. Once the southern argument of self-defense was lost, Lincoln could finally pivot to his strongest position – emancipation. Once the war became a conflict to end slavery, accepted by enough of the north, the south would lose hope of diplomatic recognition by European powers hungry for cotton. The book will conclude on January 1, 1863, with the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Historian Louis P. Masur October 31, 2024, Washington Post book review of Hamilton’s work hits the nail right on the head as he writes: “Lincoln too would dramatically transform his side’s military strategy. Much to the dismay of abolitionists, and biographer Hamilton as well, Lincoln initially refused to take direct action to emancipate the enslaved in the Confederacy. Radical Republicans were especially enraged when, in September 1861, Lincoln forced Gen. John C. Frémont to rescind Frémont’s unauthorized order declaring martial law and freeing the enslaved in Missouri. Lincoln offered the legal and political argument that the order stood outside military necessity and served only to alienate the four slave states remaining in the Union, of which Missouri was one. Within a year, though, he decided on an Emancipation Proclamation that would liberate most of the enslaved people in the Confederacy; the multifaceted story of how he changed his mind, pieces of which are told in Hamilton’s book, is one of the most absorbing in all of Lincoln scholarship.

![[BLANK]](https://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/media/collectiveaccess/images/1/4/81752_ca_object_representations_media_1482_large.jpg)

(Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton)

“In truth,” Hamilton writes, “Lincoln had really no idea what he must do to win the war.” But “Davis had had no idea how to win the war, either.” These thoughts capture a truism — much of what we think about the past comes from understanding it backward. Neither Lincoln nor Davis, in the moment, knew what might work or what needed to be done or how to do it. This is why counterfactuals are so prominent in considerations of war. What if Lincoln had fired McClellan earlier? What if Davis had stopped Lee from invading Maryland? What if Lincoln had acted sooner against slavery? Hamilton is keenly attuned to the way hindsight can both enlighten and obscure, and he peppers the narrative with questions and retrospective speculations, sometimes excessively so.

There have been scores of books on Lincoln and Davis, but few that examine them jointly. Hamilton’s uncommon approach helps illuminate an observation once made by the historian David Potter, who suggested that “if the Union and the Confederacy had changed presidents with one another, the Confederacy might have won its independence.” The statement invites us to identify the qualities that distinguished Lincoln from Davis. There are many, but none more instructive than this: Over the course of four years, Lincoln grew into the job of president and commander in chief, whereas Davis remained set in his ways. This sweeping dual biography succeeds in dramatizing the reasons one triumphed and the other failed.”

(Mary Todd Lincoln and Varina Davis)

It is clear from Hamiliton’s monograph that the turning point in the Civil War did not take place on the battlefield per se. Hamilton developed the Confederate strategy that in the end resulted in an invasion of the north through Maryland and an obnoxious Proclamation on the part of General Robert E. Lee. Expecting Marylanders and Kentuckians to rally around the Confederacy, Lee and Davis were surprised when that did not come to fruition. Once the south invaded the north, the rationale that the Confederacy was a victim of northern oppression was no longer valid and acceptable to European diplomats. With the invasion of Maryland, Lincoln was driven into a corner and finally was willing to do something about slavery being the foundation for the Confederacy’s economy and military strength. Lincoln “bit the bullet” by employing the issue of millions of enslaved people as a military and moral issue.

His strategy was clear, the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing 3.5 million slaves as of January 1, 1863. This would result in Europeans refusing to recognize the Confederacy with the war now being fought over slavery. For Davis, it appeared the war would eventually be lost. But it would be his decision to allow Lee to invade Maryland that drove Lincoln to the war of attrition.

Hamilton has completed a remarkable work of narrative history with a unique approach which should be welcome to historians and Civil War buffs alike.