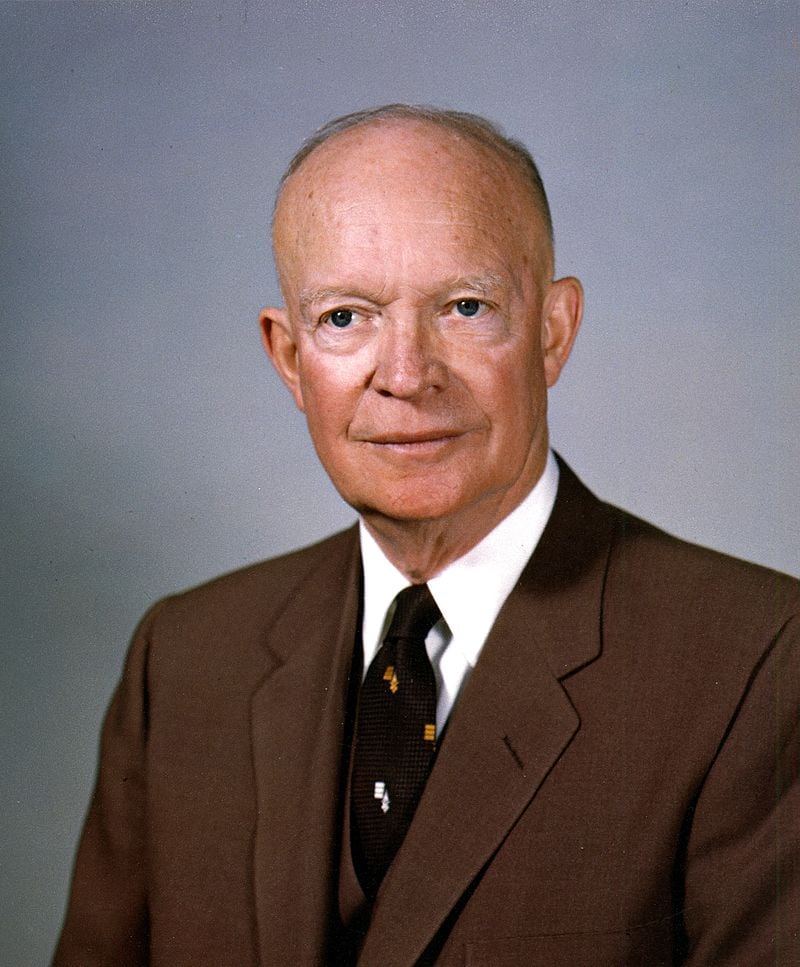

(Author Doris Kearns Goodwin with her husband, Richard Goodwin, at commencement ceremonies at UMass-Lowell on May 29, 2010)

For over ten years I had the pleasure of living and teaching in Concord, MA, a town with a deep history and a number of famous residents. One of those residents was Doris Kearns Goodwin who could be seen often on Sunday mornings at the Colonial Inn having breakfast. It was my pleasure as Chair of the History Department at Middlesex School to welcome her as a speaker at our school and expose our students to a gifted historian with a deep understanding of the American condition past and present. Her biographies of Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, the Roosevelts, and the Fitzgeralds and Kennedys stand out for their deep research, insightful analysis, and a writing style that draws the reader to her subject. Other books reflected on her experience as a White House fellow in the Johnson administration, an analysis of the leadership of the subjects of her biographies, and even a personal memoir growing up in Brooklyn and sharing a love for the Dodgers with her father. Her latest work, AN UNFINISHED HISTORY: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF THE 1960S can be classified as a biography, a memoir, as well as an important work of history assessing and reassessing the impactful events of the 1960s.

The story centers on her relationship of forty-six years with her husband Richard Goodwin, a significant historian and public figure in his own right. Theirs was a loving relationship between two individuals who loved their country and did their best to contribute to its success. Richard Goodwin, an adviser to presidents, “was more interested in shaping history,” Doris says, “and I in figuring out how history was shaped.” Their bond is at the heart of her latest work providing an intimate look at their relationship, family, and many of the important historical figures that they came in contact with. The book focuses on trying to understand the achievement and failures of the leaders they served and observed, in addition to their personal debates over the progress and unfinished promises of the country they served and loved.

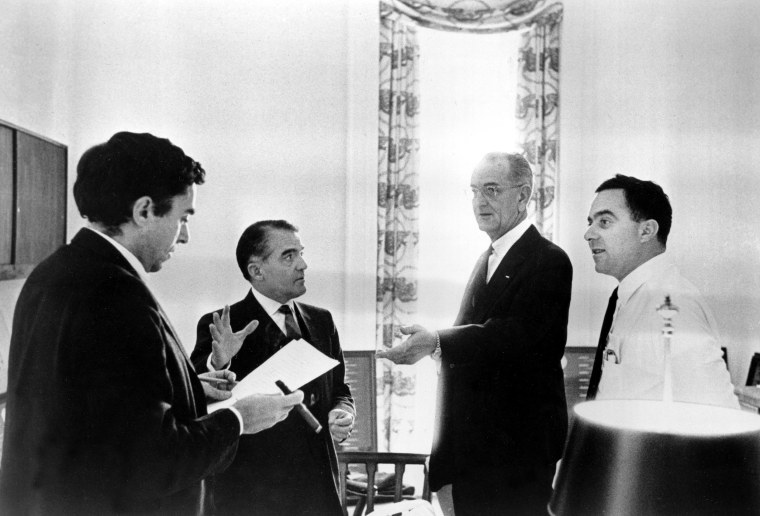

(President Lyndon B. Johnson prepares for his State of the Union address with, from left, Richard Goodwin, Jack Valenti and Joseph A. Califano, Jr. at the White House in Washington on Jan. 12, 1966)

Goodwin’s recounting of her life with her husband encompassing Dick’s career before their marriage, and then after they tied the knot. In a sense it is a love story that lasted over four decades, and it also embraces the many significant roles played by Dick and his spouse. The events of the 1960s are revisited in detail. The major domestic accomplishments and foreign policy decisions are examined in detail from the perspective of the participants in which they were familiar with and had personal relationships. Doris conducts intensive research and analysis and integrates her husband’s actions and thoughts throughout. In addition, she is a wonderful storyteller relating her own experiences and that of her spouse.

Doris begins her memoir recounting her search for the young “Dick” and searching his early diary entries and letters from the 1950s onward. She describes a young man in love with America, a theme that is carried throughout the book. Dick believed in Lincoln’s credo – “the right of anyone to rise to the level of his industry and talents – would inform every speech he drafted, every article he wrote, and every cause he pursued.” The power couple relied extensively on Dick’s personal archive which he assiduously maintained throughout his career and retirement years for many of the stories and commentary that Doris relates. This personal archive was in storage for years and emerged during their senior years, i.e.; they had 30 boxes alone on John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign.

(Bobby Kennedy)

A major theme of the memoir was “the tremor” that existed in their marriage as Dick was loyal to Kennedy, and Doris to Lyndon B. Johnson. Doris provides intimate details of their marriage and overall relationship relating to personal struggles, politics, and portrayals of prominent figures, i.e.; date night, watching the 1960 presidential debates years later, the origin of JFK’s inaugural address Dicks role in the Peace Corps, Latin American policy, including the Alliance for Progress. etc. Dick developed a special relationship with JFK which was shattered upon his assassination. Interestingly, Doris spends a great deal of time discussing Dick’s transition from an early member of the New Frontier who worked on Civil Rights among his many portfolios to taking his talents as a speech writer in support of Lyndon Johnson.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of the book is how Doris recounts meaningful events decades later. A Cuban Missile Conference in which Fidel Castro and Robert McNamara and co. attending while they were all in their eighties was eye opening, as was Dick’s meeting with Che Guevara which had implications for Dick’s career. Throughout Doris’ wit and humor are on display as she writes “here I am in my eighties and my thirties at the same time. I’m burning my life candle at both ends” as she explored the many boxes Dick kept for decades.

(Doris Kearns Goodwin with LBJ/Richard Goodwin with JFK)

The book’s depth is enhanced by the many relationships the couple developed over the years. The ones that stand out obviously are the two presidents they served, but also Jackie Kennedy, Sarge Shriver, Bill Moyers, Robert F. Kennedy, and numerous others. For Doris it was a magical marriage full of fun, love, and serious debates; she writes, “….my debate with Dick was not a question of logic or historical citation. It was about the respective investments in our youth, questions of loyalty and love.”

Dick’s reputation was formed by his almost innate ability as a wordsmith that produced so many important speeches. From JFK’s Alliance for Progress speech to formulating the term “Great Society,” to authoring the “We Shall Overcome,” Voting Rights, and RFK’s “South Africa’s Day of Affirmation” speeches which all impacted history based on who was speaking Dick’s phraseology and thoughts. After writing for JFK and LBJ, Dick turned to writing and supporting Robert Kennedy, a move that would sever his relationship with LBJ.

Perhaps the finest chapter in the book in terms of incisive analysis is “Thirteen LBJ’s” where Doris drills down to produce part historical analysis and personality study. LBJ was very moody and insecure, and he often burst out his emotions. Johnson was very sensitive about the press as he saw himself as a master manipulator and he always suspected leaks which he despised. He went as far as planting “spies” among others he feared like Robert Kennedy. Johnson’s approach to people was called “the Johnson treatment,” which is on display during his meeting with Governor George Wallace of Alabama and Senator Everett Dirkson during the Civil Rights struggles. Johnson could be overbearing, but in his mind what he was trying to achieve on the domestic front was most important.

Political expediency was an approach that Johnson and Robert Kennedy would employ during the 1964 presidential campaign when LBJ ran for reelection and Kennedy for the Senate from New York. Though they despised each other, Kennedy needed LBJ’s political machine and popularity to win, and Johnson needed to shore up his support in New York since he was a southerner. For Johnson he would rather have had “Bobby” lose, but he wanted his vote in the Senate. The LBJ-RFK dynamic dominated Johnson’s political antenna. Johnson was paranoid of Kennedy and feared he would run to unseat him in 1968. When the Vietnam war splintered America and Robert Kennedy turned against the war it substantiated Johnson’s fears. Further, when Dick, then out of government came out against the war, later joining Kennedy’s crusade, Johnson once again was livid. From Dick’s perspective he acted in what he saw as the best interests of America.

Doris nicely integrates many of the primary documents from Dick’s treasure trove of boxes. Excerpts from many of Dicks speeches, his political and private opinions, transcripts from important meetings inside and outside the White House are all integrated in the memoir. As time went on Dick turned to Eugene McCarthy and helped him force Johnson to withdraw his candidacy in 1968 after the New Hampshire primary. Dick would join Kennedy once he declared for president. The campaign was short lived as RFK was assassinated by Sirhan Sirhan in Los Angeles after winning the California primary. Dick was devastated by Kennedy’s death and would eventually attend the 1968 Democratic Convention where he worked with McCarthy delegates to include a peace plank into the Democratic Party platform. Doris was also in Chicago and witnessed the carnage fostered by Mayor Daley and the Chicago police

(Mr. Goodwin with Jacqueline Kennedy and her lawyer, Simon H. Rifkind, rear, in Manhattan in 1966. Mr. Goodwin was for years identified with the Kennedy clan)

One of the criticisms of Doris’ memoir is her lack of attention to the political right and her obsession with the middle to political left. That being said it is important to remember that this is not a history of the 1960s but a personal memoir of two people who fell in love, married in 1975, and the narrative correctly revolves around their firsthand experiences and beliefs. Doris would go on to work for Johnson after he left the White House, splitting her time between teaching at Harvard and flying to Texas , to help with his memoirs. Doris rekindles the spark of idealism that launched the 1960s which is missing today. She introduces readers to the Kennedy-Johnson successes in racial justice, public education, and aid for the poor, all important movements. In addition, she delves into the debate about the conduct of the war in Vietnam, including the anti-war movement, and the toppling of a president. Doris Kearns Goodwin has done a useful service by recasting the 1960s in her vision. It is an excellent place to start a study of the period, and its impact on what appears to be a wonderful marriage.