(German East African Campaign. A halt on the march from Kisaki to Rufiji River, January 1917. Nigerian Brigade)

Any novel that begins with the following scene has to be an attention grabber and a prelude to a superb example of historical fiction. “What do you think would happen, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt asked his son Kermit, if I shot an elephant in the balls? Father, Kermit said, keeping a straight face, I think it would hurt a great deal.” The former president was with his son on a train on June 6, 1914, in Dar-es-Salaam in German East Africa. Maybe it is more my “demented” nature, but I thought this opening was quite comical and interesting. The novel I am speaking about is William Boyd’s AN ICE-CREAM WAR which presents an anti-war message as he explores England and East Africa, the homes of interesting characters whose interactions make the novel enjoyable.

Those who have any knowledge of Theodore Roosevelt’s post-presidency will not be surprised by his presence with his son on a big game hunting expedition in Africa. Walter Smith, an American, arrived in Africa in 1909 after responding to a Smithsonian Institution advertisement for a manager to run and organize a hunting and specimen collection trip to Africa and would be in charge of Roosevelt’s adventure. Interestingly, during the expedition Smith dreamt that he found Kermit shot his father in the back. This nightmare spurred Smith to return to his farm near Kilimanjaro in British East Africa, near the small town of Tavela, a former mission station.

(A colonial Askari company ready to march in German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika), 1914-1918)

In developing his novel Boyd easily captures the ambiance of colonial rule in Africa. The poor housing, except for the rich Britons and Germans, lack of roads, the role of the military, the inherent poverty, and the use of local labor in a quasi-slave situation, all endemic to colonialism. Boyd does well with historical fiction as he nicely blends the major events of the period, the road to World War I, and what took place on the battlefield, concentrating on East Africa, a border area of present-day Kenya and Tanzania, but with repeated reference to battles in Europe.

Boyd’s writing is a blend of sardonic humor, sarcasm, and seriousness hidden amongst the dialogue and the offshoot of the war in Europe that bled over to the African continent. Some of the scenes border on the absurd and black reigns at times, but there is an underlying gravity to the events depicted and the reaction of the characters. An example of humor is clear as Gabriel Cobb, the son of a conservative military type who owns the Stackpole plantation marries Charis, his fiancé upon her return from India. He has no idea why he married her, and Boyd’s description of their honeymoon is both poignant and hilarious. One week after the wedding, Gabriel is assigned to be part of the Indian Expeditionary Force “B” set to invade German East Africa as World War I breaks out in the summer of 1914. Another example is when Gabriel’s younger brother becomes infatuated with his Oxford roommates’ sister. The problem is that Felix has a cold sore on his lip that won’t go away, and his amorous advances are rejected in a chapter that focuses on Felix’s “lip” situation and final rebuff.

The absurdity of war is carefully laid out by Boyd as the British invade the village of Tanga and its environs. Orders were either not received or when they were finally issued were not very clear. The racism endemic to the empire is on full display as British forces are made up of black Africans, Indian, South African, and British soldiers who suffer from a strong element of superiority. As Gabriel’s comments about Rajput Sepoys never being in the places they were supposed to be, and many ran away with the first sounds of German guns and artillery reflected. The British gave orders in English and many of their allies spoke only their native tongues making for interesting communication on the battlefield.

Boyd explores British society and focuses on the obligations men feel when it comes to war. Gabriel immediately does his duty and is sent to Africa, but his younger brother, Felix is rejected because of weak eyesight which is humiliating for him. He decides to attend Oxford as a means of getting away from Stackpole and embarrassment in that he is not able to fight. His father, Colonel Cobb, is not happy with his son and tells him that at times he is worthless. Felix’s roommate at Oxford, Philip Holland also is rejected by the military and suffers the same feelings of inadequacy – for him Oxford is also an escape from being with people who look down upon him.

Boyd creates three separate storylines which amazingly come full circle toward the end of the novel. First, Walter Smith and his spouse Matilda’s farm is seized by the British army for the war effort, and we follow his attempts to protect it and his interactions with his German neighbor across the border in German East Africa. Second, is Major Cobb and his two sons and the divergent paths each takes, particularly Gabriel who will be severely wounded early in his deployment. Third, the von Bishops, Erich and Leisl. Erich, a German officer, had always had his eyes on the Smith farm, and the war provided an opportunity to take it from the British and incorporate valuable machinery onto his own property. Interestingly, Leisl who is bored by her marriage volunteers at a German hospital and there she meets a new patient, Gabriel Cobb.

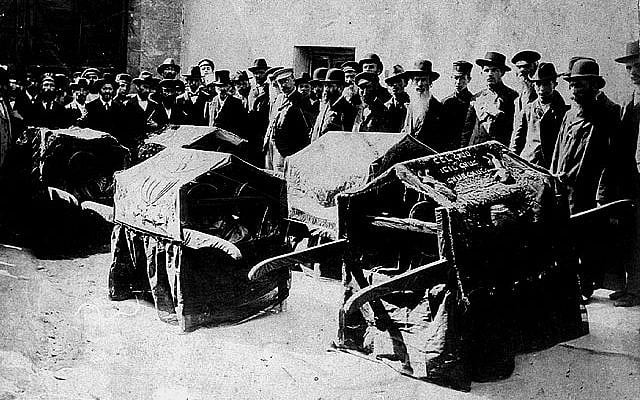

A number of situations stand out. Charis is not happy how her short honeymoon evolved and winds up having an affair with Felix and it will lead to interesting consequences. Walter Smith became an advisor to the British military since he his geographical knowledge of the region was so valuable. Finally in February 1916 the British made their move against the Germans at Salaita. During the fighting Smith leaves the battlefield to check on his farm. Upon arriving he experiences a horrible smell, and it seems that German troops have defecated all over his house and other buildings, dug up the grave of his daughter, in addition to stealing his expensive Decorticator machine which he could not run his farm without. Erich von Bishop is responsible.

Charis like many women had married right before their husbands were shipped out to fight. For many, they really did not know their partners very well which more than likely would lead to marriage difficulties upon their return – if they returned. The loneliness of these women would lead many of these women to engage in affairs while not knowing if their husbands were alive or dead. In Charis’ case it would lead to a fateful decision.

Boyd exposes the acute skepticism concerning the war in Africa as more men died of disease caused by unsanitary conditions, lack of food, and poisoning. Others would succumb to their wounds because of the lack of proper medical care and supplies. Many would contract PTSD which would lead to numerous complications for those conducting the war.

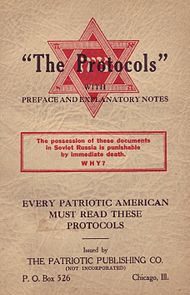

(Map of the proposed Mittelafrika with German territory in yellow)

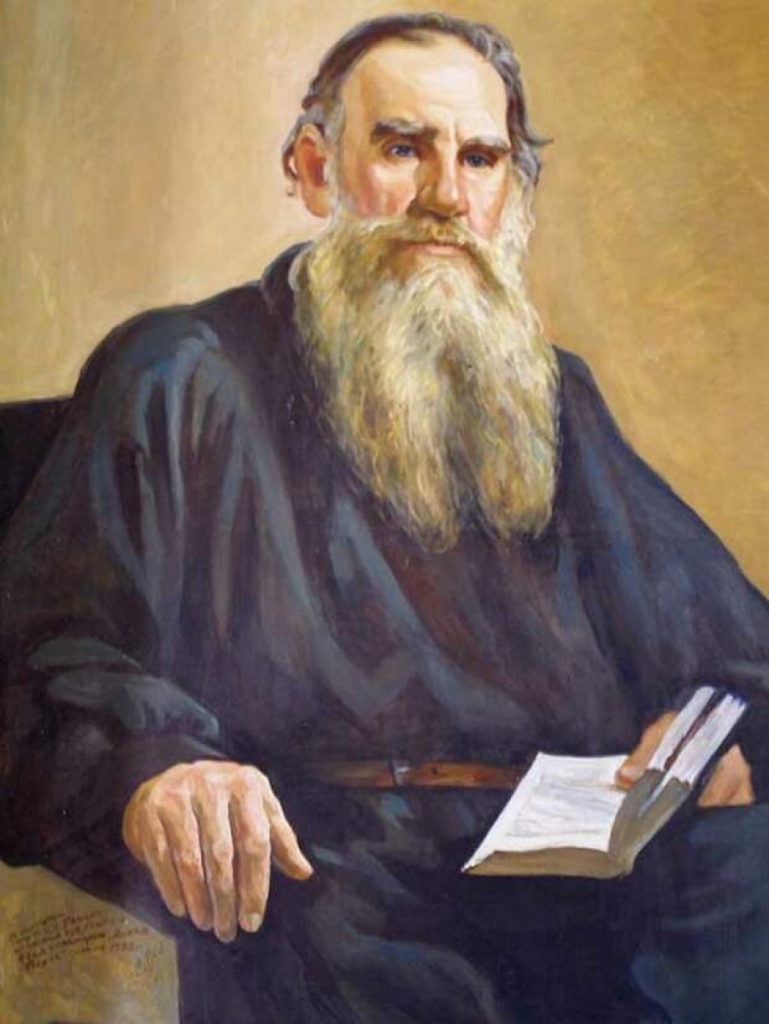

The author develops a series of important characters that dominate the story. Major Cobb, the family patriarch at Stackpole is an ornery man who is a tight fisted individual who possesses little empathy, and each day reads bible verses to his family. Walter Smith is a well meaning American who settled in East Africa who is obsessed with expanding his farm. Erich von Bishop has a typical German mentality in that he wants to expand his farm, and his target is “Smithville” across the border. Of course, there is the relationship between Gabriel and Felix which dominates the story. These and other characters set the background for Boyd’s real purpose – examine warfare, how people cope with wartime and interact with each other to survive. The most interesting relationships revolve around the Cobb brothers who love and respect each other, but the outbreak of war changes their dynamic. Gabriel will spend three years in a German hospital as a patient and then assisting others as he gathers intelligence for when the British army will arrive. Felix is the opposite of his brother, but by 1917 the British were desperate for bodies to fight so they accepted him as an officer. He is sent to Africa, and his major goal is to find his brother before he receives a letter from his bride.

Boyd explores a range of human emotions throughout the novel. Guilt, infatuation, greed, and desire dominate the actions of the major characters. He will bring together some of these characters in an ingenious manner as they all seem to wind up in East Africa. Michael Gorra in his February 27, 1983, New York Times book review sums up the importance of the novel and his evaluation of the author. He writes; “In its treatment of its central theme, it fulfills the ambition of the historical novel at its best: to comprehend the past, not as the colorful backdrop to a costume drama, but as the controlling force in the lives of its characters. Such novels rarely have pleasant things to say about any individual’s position in the large scheme of the world, and ”An Ice-Cream War” is no exception. Its characters – the survivors in particular – are mercilessly knocked about by the force of historical circumstance: by the war, by the problems of commanding men whose culture they do not understand and whose language they do not even speak, by the influenza epidemic that followed immediately upon the Armistice. But Mr. Boyd sees even domestic life, as Gabriel’s and Felix’s mother sees her marriage, ”as a relentless challenge, an unending struggle against appalling adverse conditions to get her own way.” That bleak comic vision suggests the early Evelyn Waugh, and ”An Ice-Cream War” is a good enough novel, for all its flaws, to persuade me that Mr. Boyd, who was born in 1952, may someday write a great one.”

(Advance on Kilimanjaro)

![Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the SD (Security Service) and Nazi governor of Bohemia and Moravia. [LCID: 91199] Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the SD (Security Service) and Nazi governor of Bohemia and Moravia. [LCID: 91199]](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/bcadb828-8352-4ddb-9350-f28080c6a055.jpg)