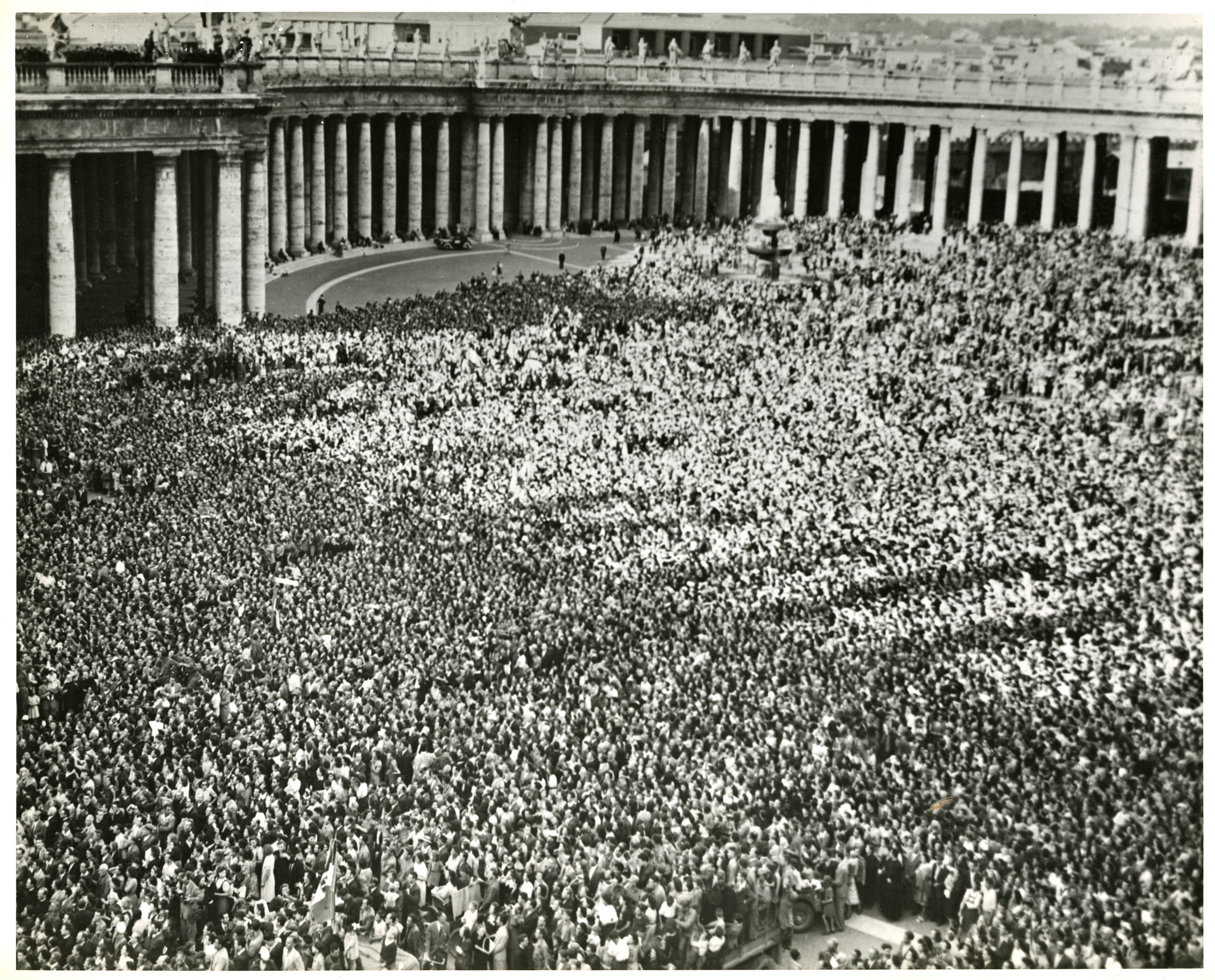

(Vatican City, 1945)

Two years ago, I read an impactful novel written by Joseph O’Conner entitled MY FATHER’S HOUSE that centered on the role of Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty, an Irish Catholic priest and senior official of the Roman Curia who was responsible for saving 6500 allied soldiers and Jews during World War II. He had the ability to evade traps set by the Gestapo and Nazi SD earning the nickname, “The Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican.” O’Connor’s portrayal is one of suspense and intrigue creating a gripping World War II drama featuring the unlikeliest of heroes who did battle with SS Commander Paul Hauptmann who failed to corral the principled Vatican official.

O’Conner has returned with a strong sequel, THE GHOSTS OF ROME, which mirrors the same approach toward historical fiction dripping with action, and unforgettable characters. In his latest work O’Conner reintroduces the “Choir,” a ragtag group dedicated to spiriting those threatened by the Nazis to safety. As World War II winds down, this covert group successfully leads untold numbers of escapees out of Nazi controlled Rome along a secret route called the “Escape Line.” Once again, Hauptmann is ordered to destroy O’ Flaherty’s underground railroad – this time his family is seized by the Gestapo and imprisoned in Berlin until he accomplishes his task.

O’Conner begins the novel on Ash Wednesday, February 1944 as he introduces an eclectic group, all members of the “Choir” as they shelter from Nazi aerial bombardment. They are an interesting mix of people consisting of Giovanna Landini, a Countess, leftist who became a Red Cross motorcycle courier when the war broke out; Sir Francis D’Arcy Osborne a British diplomat to the Holy See; Marianna de Vries, a Swiss reporter writing a book on the “Hidden Rome”; Delia Murphy-Kiernan, the de facto ambassador of Ireland to the Holy See and her daughter Blon, a university student; Sam Derry, a tough British soldier who escaped Nazi imprisonment; John May, a British jazz musician; Enzo Angelucci, a wise cracking newspaper vendor; and Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty. As O’Conner introduces these characters, another is descending by parachute into Rome trying to avoid German fire as he hits the ground.

(St. Peter’s Square, 1945)

The author offers a series of storylines in the novel. First, as part of a continuation from MY FATHER’S HOUSE, is SS Commander Hauptmann’s attempt to shut down the “Choir” and its “Escape Line.” Second, is Countess Landini and Monsignor O’Flaherty’s prolonged attempts to hide escaped POWs, airmen, and others throughout Vatican City. Third, the battle to try and save a downed Polish pilot named Bruno Wisniewski. Lastly, the intertwining of the “Choir” and the diverse personalities and beliefs of its members as they tried to reach consensus as to what actions they should pursue. O’Conner integrates a series of interviews of some of the main characters given a 15-20 years after the war to fill in historical gaps, personal observations, and tightening the story. These made up texts from letters to memoir extracts to interview transcripts are important for the reader’s understanding.

O’Conner provides a tour of Roman historical sites as the diverse characters navigate Roman streets above and below ground in their cat and mouse game with the SS. In addition, the author provides a glimpse into the Nazi occupation of Rome which by February 1944 is dominated by increasing black market prices, a lack of food and other essentials including sanitation, constant bombing raids, and the omnipresent fear of being arrested by the SS, interrogated, and executed. As O’Conner takes the reader through the catacombs of Vatican City, particularly under St. Peter’s one is reminded of the novels of Steve Berry and Dan Brown for plot development and anticipation.

There are two watershed moments in the novel. The first centers on Heinrich Himmler’s warning to Hauptmann that Hitler wanted the “Choir” to shut down or the SS commander’s family would be the price for failure. Hauptmann’s wife and children were returned to Berlin where they would be guarded by Himmler’s henchman – the warning was clear, “smash the Escape Line or face the inevitable.” The second occurred on March 23, 1944, when the Roman resistance in the guise of pavement sweepers attacked a 156 German troop column with a 40 lb. bomb that killed 30 and wounded countless soldiers. The bombers would escape, and Hitler ordered 100 Italian civilians to be killed for every German soldier who died within 24 hours. Hauptmann would prepare a death list of people who hid POWs, Communists, Socialists, members of trade unions, journalists to be killed in retribution. Victims were sent to caves where they were shot 5 at a time known as the Ardeatine Massacre.

(The band of the Irish Brigade of the British Army plays in front of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, June 12, 1944).

THE GHOSTS OF ROME do not measure up to MY FATHER’S HOUSE in terms of pure excitement and thrills. It continues the story but with more dialogue and less action. It is still a strong historical novel, but with a more laid back approach, though the underlying fears and emotions of the characters easily come to the fore. As is the case in both novels, O’Conner has the knack for creating memorable characters and scenes. Perhaps the best in the current story is the character of Manon Gastaud, a medical student under Professor Guido Pierpaolo Marco Moretti, a superb surgeon, who happens to be pro-Nazi. The conundrum rests on how to save the Polish pilot who was wounded as he descended from his airplane. Most of the “Choir” members are committed to saving his life, no matter the cost and its is the pugnacious Gastaud who volunteers to operate on Bruno despite the fact she has never performed the type of operation that is needed. With a lack of medical supplies, an acceptable site to operate, and the fear of the SS, the “Choir” takes the risks necessary to save the pilot.

Important relationships abound in the novel. There is the haunting connection between Hauptmann and Countess Landini centering on his obsession with her palace which he seized and how she leads him on in the hope of providing misinformation that would work to the “Choirs” benefit. Another is O’Flaherty and Landini’s bonding and how in another life they could have been more than wartime compatriots. The commentary of John Moody, an American soldier, and a wisecracking charmer is priceless as O’Conner injects sarcasm and humor whenever possible.

In terms of historical accuracy, O’Conner does an exceptional job producing the ambiance of wartime Rome, but also the characters of O’Flaherty and Hauptmann. The Monsignor character as mentioned earlier is based on a historical figure. The Hauptmann character is fictionalized, but the character itself is based on Herbert Kappler, a key German SS functionary and war criminal during the Nazi era. He served as head of German police and security services in Rome during the Second World War and was responsible for the Ardeatine massacre. With the completion of volume two, O’Conner’s conclusion is useful as it creates further interest for the reader to continue on to the third volume as it is not clear in which direction O’Conner will go. Volume one focused on Monsignor O’Flaherty, the second, Countess Landini, one wonders what or whom the emphasis will be on in volume number three.

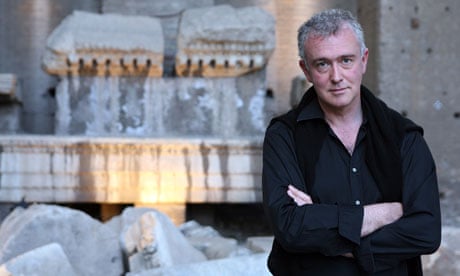

(Irish author Joseph O’Connor at the Festival of Literature in Rome)

According to Alex Preston in his February 4, 2025, New York Times Book Review, “Escaping the Nazis, With Help From a Priest and a Countess,” O’Connor has often been likened to the great Irish modernists for the lyricism of his voice-driven novels. But “The Ghosts of Rome” — which despite being the second in the trilogy can be read as a stand-alone novel —also situates him within a broader European tradition of memory and moral reckoning, one that returns again and again to World War II.

O’Connor embraces this legacy while transcending its clichés. His Rome is not merely a setting but a crucible, a city where the sacred and the profane collide, where resilience is forged in the shadow of ruins. By crafting a chorus of voices, he ensures that no single narrative dominates, reflecting the messy, multifaceted truths of history — both the way it is lived and how it is constructed in retrospect. What emerges is not just a wartime thriller, though it is that, but a meditation on how we remember, how we resist and how, even in the darkest times, humanity endures.

(St. Peter’s Basillica, 1945)