(A portrait of Chaim Grade Image by Yehuda Blum)

In the tradition of Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer and his younger brother, Israel Joshua Singer, both Yiddish novelists, Chaim Grade last novel, SONS AND DAUGHTERS captures a way of life that no longer exists – the rich Yiddish culture of Poland and Lithuania of the 1930s that the Holocaust destroyed. The novel, which is finally available in English was originally serialized in the 1960s and 70s in two New York based Yiddish newspapers, dissects the lives of two Jewish families in early 1930s Poland torn apart by religious, cultural, and generational differences.

Grade who passed away in 1982 was one of the leading Yiddish novelists of the 20th century. His novel, RABBIS AND WIVES was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1983 and his last book was expertly translated by Rose Waldman from Yiddish to English. SONS AND DAUGHTERS is a sprawling and eventful novel that takes place in the villages of Morehdalye and Zembin and depicts daily life as it unfolds among two families of rabbis that are splintering as they face the pressures of the modern world. The rabbis, Sholem Shachne Katzenellenberg and Eli-Leizer Epstein possess wonderful reputations as Torah scholars and leaders of their communities. Interestingly, Sholem Shachne is the son in law of Eli-Leizer, and both belong to different generations and beliefs of their children. They differ in religious stridency, the grandfather is stricter, but in no means is the son in law lax, even though he is more lenient. Both expect their sons to become rabbis, or at least Torah scholars, and their daughters to marry men of the same persuasion. Grade is the perfect novelist to convey this type of story as he was raised Orthodox, studied in Yeshiva as a teenager, but developed a strong secular view of life. Having lost his family in the Holocaust, he resettled in New York, remarried, and turned to fiction, writing in Yiddish.

The revolt by the younger generation against orthodox Judaism drives the novel’s plot, though Grade doesn’t forfeit his sympathy with old men who are trying to keep Judaism alive. The Sholem Shachne family is developed first as his children rebel against their religious upbringing. In his discussion with his son in law, Yaakov Asher Kahane we learn how each child rebelled. Bluma Rivtcha, perhaps the most attractive character in the novel, leaves home to attend nursing school in Vilna after her father fails to negotiate a successful arranged marriage. Naftali Hertz, the eldest son ran away to study at a secular university in Switzerland, earning a doctorate in philosophy and married a Christian woman who gave birth to a son who was not circumcised. Tilza, Sholem Shachne’s daughter is married to Kahane, but their marriage has issues as she does not want any more children with her husband as she rejects the life of a rebbetzin. Bentzion leaves for Bialystok to study business, and the youngest son, Refael’ke wants to join the pioneer Zionists and run off to Palestine. For their father there is a constant debate in his psyche as to the way his children have rejected the rabbinical life and what role he played in their decisions. He possessed internal demons, and he had to admit to himself that he had not been successful in instilling in his children the sense and strength to rebuff the modern trends developing in Poland in the early 1930s.

Grade’s writing apart from dissecting the rabbinical community embodied in Jewish family life is also an ode to nature as he describes the weather, the leaves, the trees, the Nariv river, fruit, lush green foliage that surrounded his village. Grade also describes inanimate objects with the same degree of detail and emotion, items like dishes, cups, glasses, figurines are all part of his approach. Grade also discusses his characters with the same introspective scope he applies to nature and objects through the diverse personalities he presents which allows the reader to gain an understanding of the Orthodox Jewish world of the period. In addition, we witness the arguments and disagreements between different rabbis and diverse individuals which at times reflects the similarities between the old world and the oncoming secular environment.

The Katzenellenbog family is at the center of the novel. The travails brought on by some of the children are fully explored, but Grade integrates the lives of other families, particularly that of Eli-Leizer Epstein, the Zembin rabbi who refuses to allow Jews to travel on the sabbath or attend any form of entertainment. The conversations between Sholem Shachne and Eli-Leizer are emblematic of the crisis in Judaism as it is confronted by an increasingly secular world. Both feel betrayed by their children as they torture themselves in trying to rekindle old world beliefs among family members.

Grade does a marvelous job developing interesting characters who epitomize the crisis in Judaism but also the character traits of people who are not part of the rabbinical world. Chavtche, one of Eli-Leizer’s four daughters despised her father’s third wife, Vigasia, who she believed was robbing her inheritance for her own sons. Further, she lived off her sister, Sarah Raizel’s money, who had a fulltime job. When Eli-Leizer wins a lottery much to Chavtche’s chagrin, he and Vigasia decide to devote the money to rebuild the Talmud Torah where orphans had been living in squalor. Chavtche is a selfish and jealous person emitting the characteristics of many people.

Refeal Leima is another sibling who left for the United States as he grew tired of the strict religious life fostered by his father and became a rabbi and Rosh Yeshiva of Chicago which practiced a less orthodox approach to Judaism. Shabse Shepsel, Eli-Leizer’s eldest son suffered from what appears to be a manic-depressive personality with delusions of grandeur as he changed his avocation repeatedly. He married Draizel Halberstadt because of her impressive dowry. He would deplete her wealth with a number of faulty business decisions but would move back to Zembin and purchase a house near his father who he disrespected. Grade uses his character as a vehicle to explain the religious dichotomy that exists throughout the novel. In fact, Grade describes him as “half demon and half schlemiel.” It seems that Shabse Shepsel is stalking his father and trying to humiliate him. But in the contorted logic of the rabbinical student mind, he also defends his father in a dispute over the teachings of the Tarbus school, where one of the teachers described his father an “an old, senile dotard who expects Jews to sit with folded hands here in exile until the Messiah comes and redeems us.” He further argued that the faithful hide behind their mezuzahs in the hopes it will protect them against the perpetrators of pogroms. Shabse Shepsel’s dichotomy is on full display as he humiliates his father in private and defends him in front of his congregation leading Eli-Leizer to try and convince his son in Chicago to send for Shabse Shepsel if at all possible due to America’s stringent immigration quotas.

Grade creates a number of important characters apart from the two main rabbinical families. We meet Rabbi Zalia Ziskind Luria, the head of the Silczer dynasty and father of the protagonist, Marcus Luria. He is described as an ascetic sage, burdened by the suffering of others and trying to keep Judaism alive in a world where the younger generation is rebelling against it. He is a complex character, portrayed with both sympathy and a sense of the harsh realities of the world he inhabits, seeming to absorb the pains of others as his own, reinforcing his depressive personality which fostered hatred on the part of his family. Further, as a favor to his friend, Sholem Shachne he tutored Naftali Hertz at his yeshiva to try and reinforce Judaism, however, it failed, and he would soon flee for Switzerland where he failed to fully free himself from his intense Orthodox upbringing. Marcus Luria, however, is a young man who also abandons his studies at rabbinical school after becoming wealthy in the stock market, signifying his rejection of his father’s traditional Jewish path. Marcus is seen as a pawn of trendy ideologies, who unlike his father embodies the younger generation’s revolt against traditional Judaism, and sees himself as a follower of Friedrich Nietzsche, and eventually turns to communism. Lastly, Grade introduces Khlavneh Yeshurin, an aspiring Yiddish poet, seemingly modeled on himself. Khlavneh is the fiancé of Sholem Shachne’s daughter Bluma Rivtcha and strongly believes that secular Yiddishists like himself hadn’t rejected Judaism, but rather, they understand religion and Jewish folklife differently than their predecessors.

It is clear from Grade’s portrayal of Judaic Polish society with its petty jealousies, fervent scholars, crooked businessmen, class consciousness, dysfunctional families, constant conflict between religious and secular issues, fears of political movements, in this case Zionism in actuality mirror the same types of conflicts that exist among people in the gentile world. As a former Yeshiva student, Grade was well trained in the art of Talmudic debate. Unlike the first half of the novel, which describes the horrible reality the Polish Jews will face on the eve of the Holocaust, the second half of the novel accentuates the philosophical which is highlighted by arguments between Naftali Hertz and Khlavneh. It is in the protracted philosophical arguments that the author’s talents dominate.

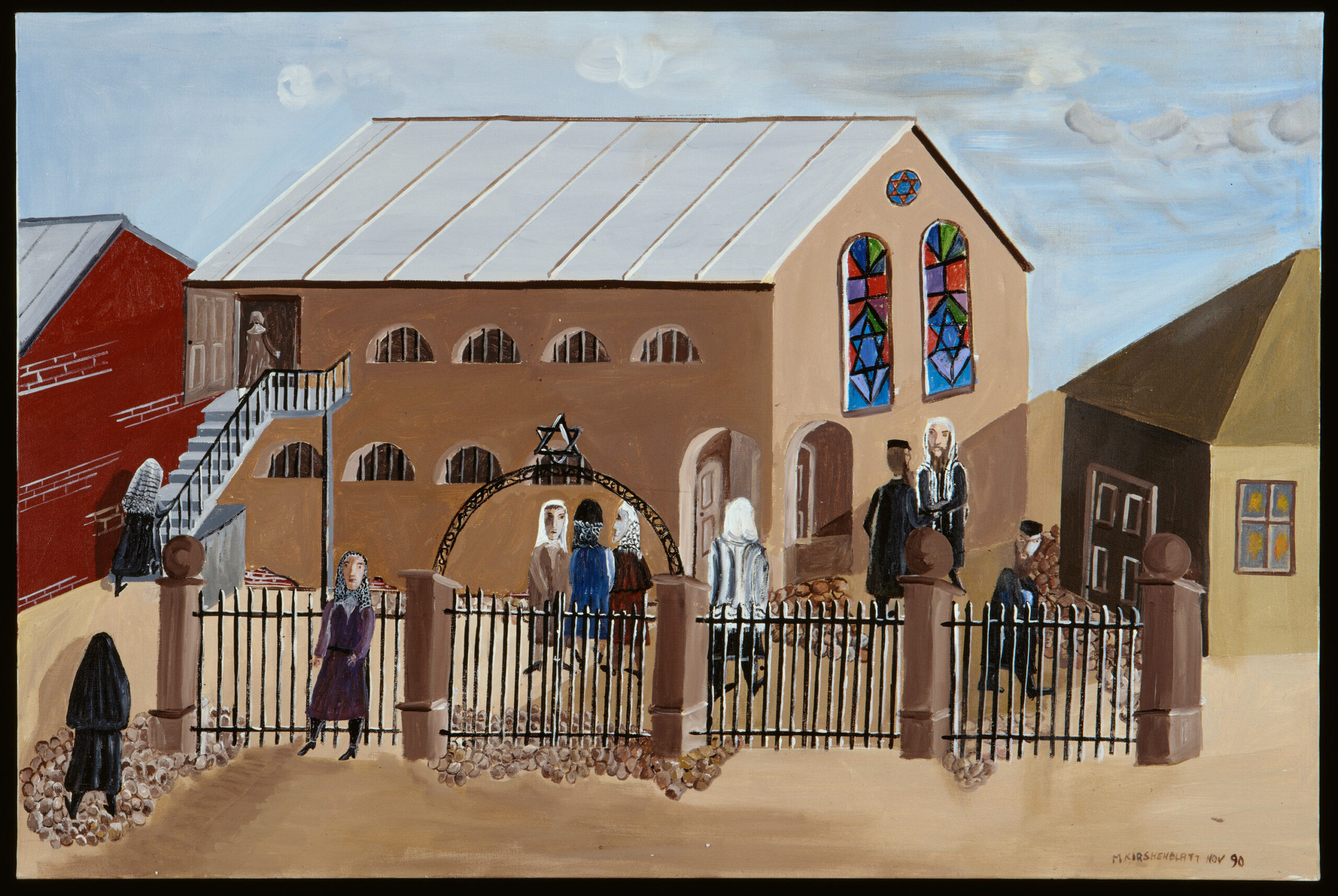

(Jewish Street in Opatów, 1930s. Photo credit: the collection of J. Brudkowski)

One of the characterizations of the rabbinical world that Grade describes concerns Dwight Garner’s label that SONS AND DAUGHTERS is a beard novel. Writing in his New York Times book review of March 30, 2025, Garner states; It’s a great beard novel. The emphatic facial hair possessed by Grade’s rabbis and Torah scholars curls luxuriously around the margins of nearly every page. Here is a typical sentence: “Eli-Leizer’s mustache was still moist from the meal, and some dairy farfel noodles stuck to his beard.” And: “Avraham Alter Katzenellenbogen’s beard hung stiffly from his chin to his waist, as if it were made of porcelain like a seder plate. Who can trust these new, clean-shaven, Americanized rabbis? The greats of the Torah had beards so bushy they could hold water.”

The issue of how to raise one’s children emerges in numerous discussions. Sholem Shachne’s wife, Henna’le complains to her husband that had he been more flexible his children would not have run away. He wonders: “where they disobeying him because he slapped them too frequently, or because he hadn’t slapped them enough?” The doubts and inner thoughts of parents reflect this dichotomy which can be applied to modern children as well as rabbinical ones. Other issues that Grade integrates into the novel include the role of Zionism in Palestine, the ideas of Marx and Nietzsche, the allure of America, arranged marriages, the selling of kosher and non-kosher clothing, the overcrowding in rabbinical homes, what do trees tell us, and the beauty of certain foods. All are part of an intense examination of the orthodox world but also told with a great deal of humor. What stands out is a remark by Naftali Hertz who ruminates on children who have been bequeathed an inheritance which is basically growing up in a shtetl, and its impact on their lives which in the end is why they desert their family and home.

As the book begins to wind down, parents and children begin to soften toward each other, but since Grade never finished volume two of the novel (it was to be written in two parts) we do not know how the familial tensions were resolved. But at the same time modernity cannot be stopped as Jewish socialist youth groups parade through villages, and more concerning, anti-Semitic Polish nationalists mount a successful boycott against Jewish merchants across the region.

In her article describing SONS AND DAUGHTERS appearing in the April 2025 edition of The Atlantic Judith Shulevitz relates that “Toward the end of the book, Grade unites life and fiction in the character of a lapsed yeshiva bocher (student) named Khlavneh who has become a Yiddish poet. He is the fiancé of Sholem Shachne’s daughter, the one who went to Vilna to study nursing. Lest we fail to grasp that Khlavneh is a self-portrait, Grade drops hints. The daughter, for instance—an attractive, spirited woman, perhaps the most appealing figure in the novel—is named Bluma Rivtcha, a rhyming echo of Frumme-Liebe, the name of Grade’s murdered first wife, also a nurse and also the daughter of a rabbi. Bluma Rivtcha brings Khlavneh home to meet the family. Over Shabbos dinner, the brother who moved to Switzerland and no longer observes Jewish laws ridicules him for writing poetry in “jargon”—that is, Yiddish, the bastard language of the uneducated Jew, “a common person, an ignoramus, a boor”—rather than in Hebrew, and for thinking that he and his fellow Yiddish writers could capture the spirit and poetry of Jewish life without following Jewish law themselves. Khlavneh refutes the brother in a brilliant show of erudition, then concludes: “You hate the jargon boys and girls because they have the courage to be different from their fathers and grandfathers, even to wage battles with their fathers and grandfathers, and yet, they don’t run away from home. The father, who everyone thinks will be offended by a guest’s outburst at the Sabbath table, laughs in delight. Grade, having fashioned a world in which the old fights mattered, now gets to win them.”

Rose Waldman, the translator provides interesting insides in her note at the end of the novel. She describes Gade’s personal dilemma as he experiences “the tension between his desire to live and write like a secular human being in a modern world and the constant nostalgic pull of his Yeshiva past, the traditional Jewish Vilna of his youth.” For Grade sees himself as “a thoroughly ancient Jew, while the man inside me wants to be thoroughly modern. This is my calamity, plain and simple, a struggle I cannot win.” This dichotomy is pervasive throughout the novel. Waldman does the reader an important service by tracing the history of the novel’s preparation for publication and the difficulties that arose due to the fact that it was incomplete. Grade was prepared to write a two volume novel but never completed the second volume. However, the translator discovered some of Grade’s ideas for the second book and its ending, which she includes in her note which provides the reader with a semblance of a conclusion.

The tortuous rabbinical arguments are on full display throughout the novel as the characters dissect the Torah, Mishna, and Gemora, and other sacred texts of Judaism as they apply them to their modern situations. These commentaries can appear to be provincial but in their day were the rule of law and every yeshiva bocha (which I was one in the 1950s and 60s!) must conform to. In the end Grade’s novel overflows with humanity and heartbreaking emotions for a world, once full of life with all of its contradictions, that within a decade of the novel’s setting would be destroyed forever.

In closing, Grade never mentions the coming Holocaust in the book, however its future existence is felt on every page. According to Yossi Newfield in his February 24, 2025 review in the Yiddish newspaper, Forward; “In some sense, SONS AND DAUGHTERS can be considered a Holocaust memorial, as the events it describes foreshadow the upcoming annihilation of Polish Jewry. It is this tragic awareness that animates Grade’s questioning and demand for answers from the rabbinic establishment, from the Torah, and from God himself.”

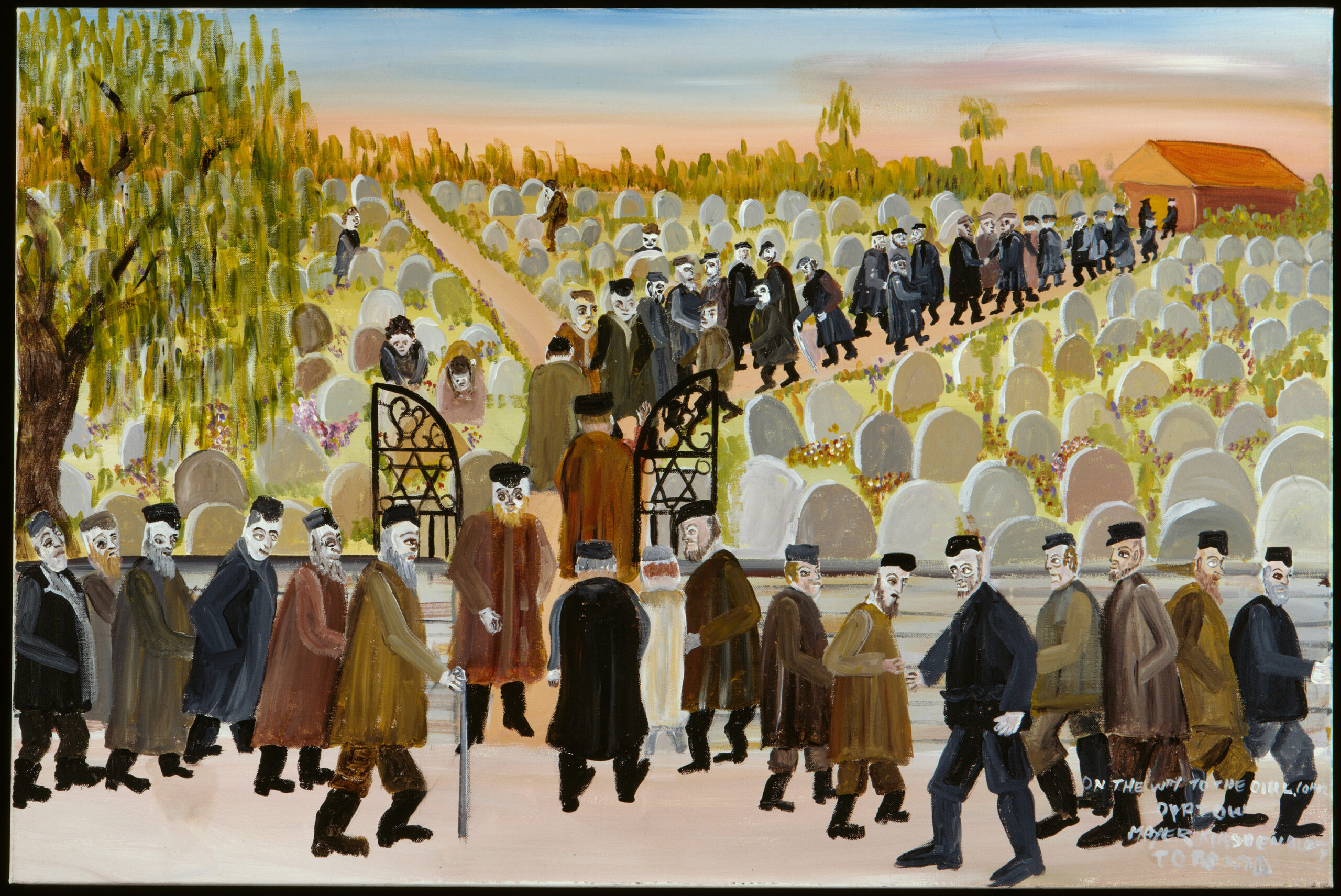

(Chaim Grade wrote “Sons and Daughters” during the 1960s and ’70s.Credit…YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)