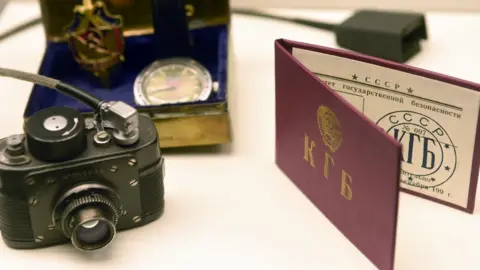

(The Lubyanka Building in Moscow, Russia, is most famously known as the former headquarters of the KGB (Soviet secret police) and now houses the FSB (Federal Security Service)

For six seasons between 2013 and 2018, “The Americans,” an American spy drama television series aired on the FX channel. It depicted the Jennings family as a typical suburban American family. There were two teenagers and parents who happened to be KGB spies at the outset of the Reagan administration who try to come across as your average American family grouping. Their job was to spy on the United States during a period when the Cold War was escalating. This Kremlin strategy of embedding spies in the role of everyday citizens was not an aberration as since the Russian Revolution brought the Bolsheviks to power, Moscow began deploying Soviet citizens abroad as deep-cover spies, training them to fit into American society and posing as different characters. In our current heightened environment with Russian aggression in Ukraine, interference in American elections, and Vladimir Putin’s obsession with recreating the Soviet Empire it is not beyond the realm of possibilities that Russia has continued this strategy today.

In his latest book, THE ILLEGALS: RUSSIA’S MOST AUDACIOUS SPIES AND THEIR CENTURY LONG MISSION TO INFILTRATE THE WEST, Shaum Walker, an international correspondent for The Guardian brings the Russian strategy to life as he explores the KGB’s most secretive program. His excellent monograph conveys a thrilling spy drama culminating with Putin’s espionage achievements as the Kremlin continues to infiltrate pro-western countries worldwide. In the current international climate Walker’s study is an important one as we try to combat Putin’s autocracy, particularly in light of Donald Trump’s seeming infatuation with the Russian autocrat.

Ishkak Akhmerov (undated)

Walker begins his study by introducing the reader to Ann Foley and her husband Don Heathfield, and their two sons Tim and Alex, However, in reality they were Russian spies; Elena Vavilova and Andrei Berzukov who had lived as a couple in Cambridge, MA for years. They would be arrested by the FBI and deported back to Russia in 2010. Their vocation was part of “the Illegal” program.

Illegals were recruited by the KGB. They were ordinary Soviet citizens who were given years of training to mold them into westerners. During the Cold War, the illegals living in the west were told to lie low and wait. Once the Soviet Union collapsed, the KGB was disbanded. However, once Putin assumed power he began to restore Russian spy capabilities, including “the Illegals” and a fresh batch of operatives was trained. Walker correctly argues that flying illegals based in Moscow on short term missions to assassinate enemies of the Kremlin abroad was standard policy. “A new army of ‘virtual illegals’ impersonated westerners on social media and were a key part of Russia’s attempts to meddle in foreign elections. Even if the era of long term illegals seemed over, the concepts underpinning their work remained at the heart of Russian intelligence operations.” It is clear that at various points during the last century the era of illegals seemed to be over. However, each time Russia’s spymasters resurrected the program. Today, a network of SVR safe houses scattered around Moscow has produced a new generation of operatives undergoing preparation for deployment overseas. They spend their time honing the pronunciation of target languages, studying archives of foreign newspapers and magazines to absorb culture and social context, and memorizing details of their cover stories. Soon, this new generation of illegals will be deployed to live what appears to be mundane lives in various locations around the world, while secretly implementing Moscow’s agenda.

Walker lays out the early history of using illegals by discussing their use before the Russian Revolution to overthrow the Tsar, and once in power as a vehicle to be used against the west and for their own survival. The strategy is based on Konspiratsiya, defined as “subterfuge,” or “conspiracy,” – “a set of complex rules, a rigid behavioral tool, and a way of life, the overarching arm….was to keep party operatives undercover and undetected, and was used by many groups of anti-Tsarist revolutionaries.”

Walker does a credible job explaining the Bolshevik approach toward espionage especially when they did not have diplomatic recognition in the west which meant they had no embassies to hide spies. The result was to develop the illegal program further. The author describes the role of many incredible operatives and their impact on the course of history. Men like Meer Trislisser, a Bolshevik operative, and Dmitry Bystrolyotov, another Russian spy perhaps the most talented illegal in the history of the program, make for fascinating reading as they navigate their training, implement what they have learned as they integrate into other societies, how they recruited local nationals to spy for them, and how successful they were in acquiring intelligence.

(Grigulevich (Castro) and his wife during their stay in Brazil in 1946).

The program was run through the Cheka’s ION office which was in charge of the illegal program. A case in point is how they flipped an English communications officer, Ernest Oldham, into providing documents which covered much of the secret European diplomacy, i.e., impact of the depression, Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, etc. It is clear that the Soviets were far ahead of the British and Americans when it came to espionage, especially when Franklin Roosevelt granted the Soviet Union formal recognition which provided them with an embassy in Washington to run their agents. Since the American economic influence was worldwide spies were needed to ferret out US positions. In addition, the Kremlin needed to industrialize quickly, and American technological and scientific secrets were a major target led by the fascinating figure of Ishak Akmerov who would train Americans like Michael Straight and Laurence Duggan, both with strong ties to the US State Department.

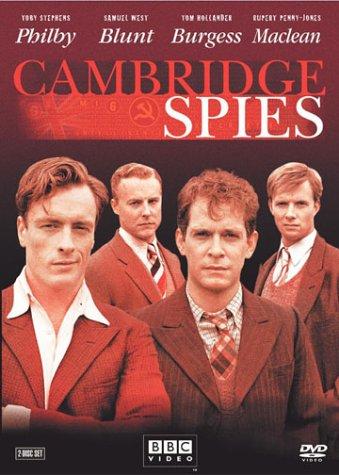

Walker’s insights into the assassination of Leon Trotsky, Stalin’s purges and “show trials” of the 1930s, and the awkwardness created by the Nazi-Soviet Pact of August 1939 reflect the role played by a series of illegals who were trained assassins and acquired the ability to hunt down anyone whom Stalin deemed a threat. Stalin’s purges would decimate the military leadership and foreign intelligence sources, but information still flowed from England from the “Cambridge 5,” who were a ring of spies in the United Kingdom that passed information to the Soviet Union during World War II and the Cold war and was active from the 1930s until at least the early 1950s. The five were convinced that the Marxism-Leninism of Soviet communism was the best available political system and the best defense against fascism. All pursued successful careers in branches of the British government. They passed large amounts of intelligence to the Soviets, so much so that the KGB became suspicious that at least some of it was false. Perhaps as important as the specific state secrets was the demoralizing effect to the British establishment of their slow unmasking and the mistrust in British security this caused in the United States. In addition, Soviet agents like Richard Sorge became friends with Eugen Ott, the Nazi ambassador to Japan who along with others provided Stalin with evidence of the impending German invasion of Russia in 1941. Stalin and NKVD head, Lavrenti Beria rejected this intelligence as scaremongering as it went against Russian official policy. In June 1941, the Kremlin would pay for their stubborn adherence to the strict laws of Marxism-Leninism and Stalin’s perceptions of Hitler who he believed would have to defeat England before he could invade Russia.

(Former KGB head Yuri Andropov)

About a quarter the way into the book, Walker turns to the Cold War and successfully argues that Stalin’s ability to negotiate a favorable postwar settlement was assisted by the work of the Cambridge 5 in England as they produced innumerable numbers of documents and intelligence. Anthony Blunt, Donald MacLean, and Kim Philby, all members of the Cambridge 5 were essential figures and Philby himself was put in charge of British counterespionage! In fact, Walker argues that Stalin knew about the atomic bomb much earlier than Harry Truman which is why at the Potsdam Conference he did not act surprised when the president warned him about the new weapons.

(Elena Vavilova and Andréi Bezrúkov, in Moscow, while training for the KGB)

Walker goes into detail concerning Stalin’s fears of Josef Broz Tito, the leader of Yugoslavia who believed in a neutral approach to the Cold War and its path toward implementing socialism. Tito was able to act in this manner because his forces liberated his country from the Nazis, which was not the case throughout eastern Europe. Stalin tasked Iosif Grigulevich, a Soviet illegal to assassinate Tito. Interestingly, earlier Grigulevich was also involved in a failed attempt to kill Leon Trotsky. Stalin would fail to kill Tito, who would remain a thorn in his side and Russia in general. The dispute with Tito would last until Stalin died in March 1953 which also saved thousands of others he implicated in the Doctor’s Plot, a conspiracy that Jews were out to kill the Russian dictator.

Many of Walker’s chapters are like a movie script for an espionage thriller. Perhaps one of the most interesting chapters deals with a Soviet agent’s ability to gain connections in the Vatican and manage to become the Costa Rican ambassador to the Vatican at a time when there was a fear in the west of a communist victory in Italy. Other fascinating chapters include the life and work of Yuri Linov, a young man who was very facile with foreign languages and began his KGB career informing on fellow students while studying at the university. By 1961 he would be trained as an illegal and deployed to the United States. Linov was very patriotic, seeing Soviet success in space with the mission of Yuri Gagarin as proof of Russian exceptionalism. Walker describes his recruitment, training, and missions in detail providing the reader with further insight into the illegal program. First, Linov would find himself in Prague during the summer of 1968 ordered to infiltrate the liberal reform movement under the government of Alexander Dubcek, and by 1970 his training and focus shifted to the Middle East as his handlers steered him to becoming the KGB’s expert on Zionism. Apart from Linov’s espionage work, Walker delves into personal aspects of an “illegal” life. He examines how his wife Tamara was chosen for him, and the difficulties their careers presented for them on a personal level. At a time when it was becoming more and more difficult to choose, train, and deploy illegals, Linov’s work seemed to be a success.

(Illegals operate without diplomatic cover and blend in like ordinary citizens)

(Illegals operate without diplomatic cover and blend in like ordinary citizens)

Walker also presents the American attempt to implement its own illegal program, and concluded it was almost impossible to train operatives in the intricacies of Soviet life and equip them with a story and documents that would stand up to Soviet security. The KGB on the other hand remained doggedly committed to a system that no longer seemed worth the enormous time and effort. The question is why? According to the author a number of reasons emerge. First, the institutional memory of success from the early Soviet period and its roots in Bolshevik idealism kept the KGB wedded to illegal work as a key part of their own internal mythology. Second, under the leadership of Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev who was in such poor health as being functionally useless as a leader that massive change could not take place. Third, by the late 1970s few of Russia’s 290 million people were permitted to leave the Soviet Union. Those who were allowed to leave experienced a lack of free movement because of surveillance. As result, the only people who had some freedom in other countries were the illegals and they became the only reliable source of intelligence for Soviet leadership.

Once Yuri Andropov headed the KGB (1967-1982) he would employ illegals as he saw fit. Having witnessed the Hungarian Revolution in 1956 as ambassador to Hungary he would use all tools at hand to block any threat to Soviet control. Prague has already been mentioned, and Andropov had no qualms about employing illegals in Afghanistan in 1978 and assisting in a coup against the regime in Kabul that would lead to the Soviet version of “Vietnam” as it would be stuck in the Afghan quagmire that ultimately led to the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Toward the end of the narrative Walker reintegrates the lives of Tracey Lee Ann Foley and Donald Heathfield into the monograph. He uses them as background to the emergence of Vladimir Putin as Soviet Premier and President. Interestingly, the two were dispatched to the United States during Gorbachev’s “glasnost” period as the KGB remained paranoid of the United States. Walker explains the meteoric rise of Putin and the restoration of the “KGB” mindset in Russia under a new organization, the SVR. Putin would rekindle the illegal program as part of a process to restore Russia to great power status which continues to this day. For a complete examination of Putin’s rise and career the two best biographies are Steven Lee Myers’ THE NEW TSAR: THE RISE AND REIGN OF VLADIMIR PUTIN and Philip Short’s recent work, PUTIN.

(SVR Yuri Drozdov had a legendary reputation in Soviet and Russian intelligence circles)

(SVR Yuri Drozdov had a legendary reputation in Soviet and Russian intelligence circles)

Under Putin, Foley and Putin would continue their espionage work and lives replicating an American couple until the FBI got wind of their work and arrested them. It is fair to conclude as does Joseph Finder in his New York Times, April 17, 2025, book review that “despite periods of diplomatic warming, Putin has never abandoned his illegals. He ordered the program revitalized in 2004, three years before his Munich speech signaled the return of Cold War tensions. While America was busy declaring the “end of history,” Russia was quietly training a new generation of agents to live among us.

Walker’s book serves as a reminder that somewhere in Russia right now, ordinary citizens are being molded into simulacrum Americans, learning to enjoy Starbucks and complain about property taxes, prepared to live among us regardless of who occupies the White House or how many summit handshakes take place. In international relations, as in life, it’s the quiet ones you need to watch.”