A few months ago, I had a conversation with an old friend from my Yeshiva days in Brooklyn. At Yeshiva and in high school we were very close, and it is the case with many people we drifted apart over the years but intermittently we kept in touch. Holiday greetings, a periodic email, or phone call were our communication over the decades, and I still have fond memories of our relationship. It was during that conversation and his reaction to a number of my book reviews which I posted on my web site that I realized that a wall might be developing between us. The foundation of our disagreement involved our reactions to events in Gaza that followed Hamas’ brutal attack of October 7, 2023, when over 1200 Israelis were slaughtered and 250 hostages were seized by the Palestinian terrorist group. In our last conversation we “agreed to disagree” as he said so we could continue our friendly catch up conversation. The crux of our disagreement rested on Israel’s reaction to the October 7th massacre which led to the destruction in Gaza making large parts of the territory almost inhabitable.

(Evgenia Simanovich runs to the reinforced concrete shelter of her family’s home, moments after rocket sirens sounded in Ashkelon, Israel, on October 7. “In Ashkelon, residents have just seconds to seek shelter before a rocket launched from Gaza could strike,” photographer Tamir Kalifa told CNN. “Evgenia yelled for me to follow her, and I pressed my camera’s shutter as we sprinted to her home a few meters away.” )

I went to the Gaza Strip in the spring of 1984 when I had a Fulbright Fellowship at Hebrew University. It was a time of war after Israel invaded Lebanon to root out Palestinian terrorists who were making life miserable for Israelis living near their northern border. When I visited Gaza I witnessed many of the living conditions that made refugee camps that were run down and squalid. At the same time, I was amazed at the beauty of the Mediterranean coast that bordered the Palestinian enclave. As a Ph. D in history who focused and published on Arab Israeli relations I am keenly aware of the positions of both sides, Arab and Jew when it came to the riots of the 1930s, the Holocaust, and events surrounding the 1948 War that led to the bifurcation of the region between differing viewpoints. I have always held the belief that peace between the two sides was almost impossible based on ideology, the emotional attachment to the land by all parties, the leadership in the region, and the role of major powers.

(Palestinians walk past the rubble of buildings destroyed during the Israeli offensive, amid a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip).

With my mindset I was fortunate to come across Peter Beinart’s latest work; BEING JEWISH AFTER THE DESTRUCTION OF GAZA where the author lays out the issues for people who have undying loyalty to the Israeli state, born of the Holocaust, seeing it always morally and ethically correct because of the neighborhood in which it resides, and those who find that the Netanyahu government, dominated by right wing nationalists had gone too far in trying to completely destroy Hamas. No one can defend the abhorrent behavior of Hamas, but at what point do we draw the line when contemplating the destruction of an entire society through collective punishment.

It seems that every Jewish person has had the conversation with friends, relatives, and acquaintances over whether as Jews we can still support a government that engages in war crimes. I realize “war crimes” is a difficult term to apply, but I must ask how else can you describe the discriminatory bombing and food deprivation of civilians who are being held hostage by Hamas that has led to the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians. It is difficult to hold these discussions with people who firmly believe that Jewish goodness and integrity translates into Israeli virtue and exempts the Netanyahu government from the normal laws of humanity. As Beinart writes, “we are not hard wired to forever endure evil but never commit it. That false innocence, which pervades contemporary Jewish life, camouflages domination as self-defense,” which is at the core of the debate.

Over the years the author has been a stalwart supporter of Palestinian rights, even as he attends shul arguing that Jews are fallible human beings. His goal as Benjamin Moser writes in the May 4, 2025, New York Times is “to wrestle with the knottiness and ambiguity in our sacred texts and correct for the omissions in the mythology of purity that so many of us were taught as children and that many continue to subscribe to as adults.”

(Palestinians walk past the rubble of houses and buildings destroyed during the war, following a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip, January 20, 2024).

Beinart relies on Jewish texts and draws lessons from South Africa, where his family is from, to confront Zionism and what he sees as complicity from the American Jewish establishment in Palestinian oppression. He argues for a Jewish tradition that has no use for Jewish supremacy and treats human equality as a core value. In his book, he appeals to his fellow Jews to grapple with the morality of their defense of Israel. Beinart has a history of changing his opinions be it his support for the Iraq War or tolerating workplace sexual harassment. Beinart’s plea is for the Jewish community to reexamine their views that would require a painful about face concerning views they have held for most of their lives.

Beinart called on American Jews “to defend the dream of a democratic Jewish state before it is too late,” especially in light of the policies perpetrated by a government whose leader is under indictment who clings to power by accommodating the right wing minority in his cabinet. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu seems to prosecute the war on Gaza as a vehicle to remain in power which would avoid a trial and his possible imprisonment. Whether you agree or disagree with the author he should be commended for his courage for standing up to what he believes is correct and accepting the consequences of the loss of friendships, anger from family members, and constant criticism and ostracization by his many critics.

One of Beinart’s major themes revolves around the argument that victimhood often feels like the natural state for Jews throughout history. But this mentality covers up the fact that Jews can be “Pharoah’s too.” This selective vision permeates Jewish life. Jews employ the bible to refute the claim that Israel is a settler-colonial state. Anything that contradicts this contemporary narrative is not accepted. Interestingly the author weaves the ideas of Vladimir Jabotinsky, an important historical figure for right wing Israelis into the narrative, i.e.; the ideology of virtuous colonization, which today has been replaced by virtuous victimhood to support his views.

(Palestinians wait to buy bread in Gaza City, February 3, 2024)

To Beinart’s credit he recounts the brutal Hamas attack of October 7 in detail. He delves into the impact on Israeli families and society and accurately concludes the entire country was a victim on that horrendous day of murder, rape, and kidnappings, not just those who experienced the immediate impact. He even points out how Israeli progressives and leftists in the United States and Europe, ones, political partners reacted with indifference to the attack and many justified Hamas’s actions. The message that was conveyed is that the killing of Jews was nothing new, it’s just the way it has always been.

Many Jews have compared October 7 to the Holocaust, but Beinart concludes there is a fundamental difference . “To preserve Israel’s innocence, it has transforms Palestinians from a subjugated people into the reincarnation of the monsters of the Jewish past, the latest manifestation of the eternal, pathological, genocidal hatred that to the Passover Haggadah, in every generation rises up to destroy us.”

(Hamas fighter outside the myriad of tunnels under Gaza)

Beinart tries to understand Hamas’s actions; in doing so he tries to explain the Palestinian mindset as they see themselves as victims of colonialism. They, like other victims in the past, have no army, so they do not follow the rules of warfare and commit barbaric acts characteristic of colonial revolt. However, countries like China and Russia have armies and they do not follow the rules of law in Ukraine, Georgia, Crimea, Chechnya, and in China’s case the victims are the Uyghur population and other mostly Muslim ethnic groups who can be considered genocide victims.

In trying to understand, it is clear “that violent dispossession and violent resistance are intertwined.” In the end Israeli oppression is not the only course of Palestinian violence. It is Palestinians, like all people who are responsible for their actions. However, Israeli oppression makes Palestinian violence more likely. It comes down to despair for the Palestinian people as it is clear there is no way the Netanyahu government will accept a two-state solution.

(Israeli soldiers carry the casket of reservist Elkana Yehuda Sfez, who was killed in combat in Gaza, during his funeral at the Mount Herzl military cemetery in Jerusalem, on Jan. 23, 2024).

In analyzing death figures put out by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and the Gaza Health Ministry it is clear that over 50,000 people have died and 20% are probably children. Beinart relies on many sources to verify these numbers, but Israeli leaders minimize the toll and shift blame onto Hamas arguing that Hamas uses human shields, seizes food and supplies targeted for Palestinian civilians, and murders any opposition. However, Beinart’s argument that Hamas’s actions are typical of other insurgent movements is no excuse and to absolve them of one iota of legitimacy is wrong and their actions are considerably heinous when compared to other insurgent movements. But Israel’s strategy to deliver as much destruction as possible in order to shock the Palestinians and get them to turn against Hamas has not been effective. Blaming the Palestinians for Hamas’s 2006 victory at the polls is not valid since the Palestinian people had little choice. Another Israeli argument that they must destroy Hamas to be safe, but it is an impossible task because the alternative Israel must offer, the ability to vote, a high degree of autonomy, and a future state will not be forthcoming so why should Palestinians opt for peace? They need a viable alternative for Hamas which is not forthcoming. In reality, as long as Israel tries to destroy each insurgent group, their actions foster the next generation of insurgents. As Palestinians believe they are not safe, they will do their best to make sure Israelis are not safe also.

In reading Beinart’s work I wondered if there is such a thing as “Jewish exceptionalism” that makes Israel unaccountable for the type of warfare they are waging. Historically I do not see it as other nations/groups have engaged in atrocities and war against civilians have been condemned with sanctions etc.

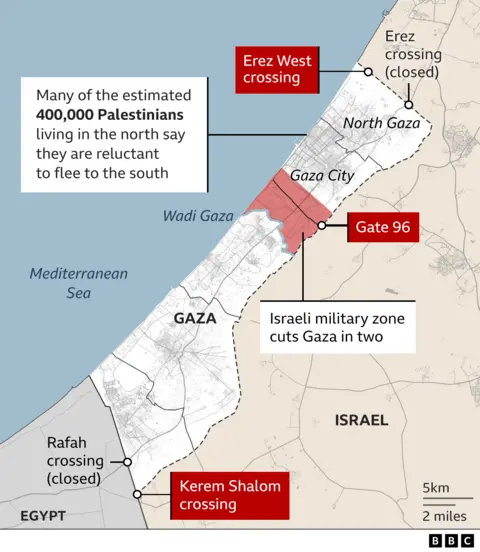

(Israeli protesters attempt to block the road as aid trucks cross into the Gaza Strip, as Israeli border police watch over them, at the Kerem Shalom border crossing, southern Israel, Jan. 29, 2024)

Another major issue that Beinart raises is that of the “new anti-Semitism.” Israel has equated any criticism of its actions as anti-Semitic as a vehicle of deflecting criticism of what they are doing in Gaza. In doing so they turn the conversation about the war into a conversation about the motives of people who oppose their actions. What is clear is that when Israel kills Palestinians, what is perceived to be anti-Semitism increases, but the Israeli government conflates anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism in order to depict Palestinians and their supporters as bigots, therefore turning a conversation about the oppression of Palestinians into a conversation about the oppression of Jews. In the end Judaism and Israel are separate and Jews, the world over should not be blamed for the actions of the Israeli government.

A great deal of Beinart’s discussion revolves around the actions of American Jews who support Israel’s policies. It seems as progressives in the United States turn against Israel they are forcing Jews to choose; defend exclusion in Israel or inclusion in the United States and some of America’s leading institutions are choosing the former.

(Israeli soldiers practice evacuating wounded people with a helicopter during a military drill in northern Israel, in preparation for a potential escalation in the conflict between Israel and the Hezbollah militant group in Lebanon, on Feb. 20, 2025)

Beinart offers a comparison of historical situations that are somewhat similar to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. He delves into apartheid in South Africa and the fears of white Afrikaners; he discusses the hatred and fears that existed in Northern Ireland until a settlement was reached overcoming Protestant fears of the IRA; the Reconstruction period in the late 19th century in the United States is explored as southern whites feared the newly freed black population and fueled by northern liberals. In these situations, the key to avoiding as much violence as possible was to give the aggrieved party the vote and a voice to express their concerns because inclusion yields greater, not total safety.

I do not believe that Beinart is naive enough to support the idea that if a settlement ever arrives between Israel and the Palestinians that peace will break out in the Middle East. In a region where Iran, Hezbollah, the Houthis, and numerous other terrorist groups abound violence will lessen, but the author’s emotional and heart felt appeal for reconciliation is really the only hope for the future no matter how impossible that appears today. I admire Beinart’s beliefs and the professional risks he has taken to engage the public in a proper debate – that should be allowed in a free society and the back and forth between those who disagree should be civil, not based on fear.