(Ebbets Field, Brooklyn, NY)

As a little boy in 1956 my father took me to Ebbets Field to see the Brooklyn Dodgers play the Cincinnati Reds. We sat behind the Reds dugout, and I carefully watched men like Vada Pinson and Frank Robinson. I looked out at the green expanse, and I saw my heroes; Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, Pee Wee Reese and was overwhelmed. I do not remember the final score of the game, but what I do remember 70 years later was how wonderful the experience was. I would never return again to Ebbets Field, not because my parents refused to take me, but because Walter O’Malley, a man who would be vilified and hated by the Flatbush faithful, would move the “beloved Dodgers” to the west coast. I have read a number of books on the move, the best being Neil Sullivan’s THE DODGERS MOVE WEST, but none zero in more on the man responsible for changing baseball from a conservative midsize business that resided on the east coast to a national, and then international game earning billions of dollars. The publication of Andy McCue’s exceptional biography of O’Malley and the history of the move, WALTER O’MALLEY AND THE DODGERS AND BASEBALL’S WESTERN EXPANSION fills that void.

McCue goes right to the heart of why O’Malley wanted to move the Dodgers to Los Angeles. After spending about a third of the book providing background material relating to the development of baseball and the Dodgers in particular. He integrates O’Malley’s upbringing, his early career, which was primarily focused on the law and business, even though he was involved with baseball, but with a special emphasis on real estate transactions. Further he does well integrating the machinations within the Dodger organization from the 1920s on as different factions vied for control of the ball club. What emerges are wonderful portraits of Branch Rickey, Buzzy Bavasi, and Leo Durocher, among others. But more importantly he drills down as to how O’Malley was able to acquire his controlling interest in the team. Once McCue reviews this material he goes right to the heart of why O’Malley wanted to move the Dodgers to Los Angeles.

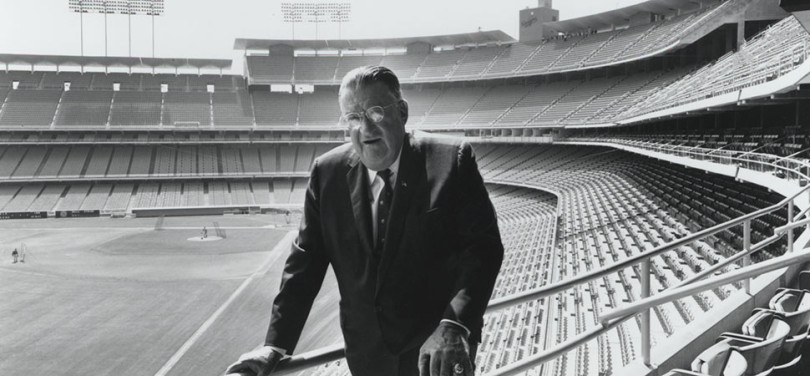

(Walter O’Malley outside of his office on the Club Level at Dodger Stadium)

In a chapter entitled “A New Stadium-Economics,” McCue outlines the state of the Dodgers in the early 1950s getting to the core of O’Malley’s concerns. One of the primary themes of the narrative is that O’Malley was a businessman foremost, and to a lesser extent, a baseball fan. By the early 1950s Brooklyn underwent a demographic and racial change especially where Ebbets Field was located. The area, known as Flatbush, was becoming less white and more diverse. Brooklyn in general experienced the same thing as between 1950 and 1957 the borough “lost 235,000 Caucasians and added 100,000 non-whites.” Brooklyn was losing population as people fled to Nassau country, Long Island, and Queens. In addition, the borough was also losing manufacturing jobs, and as a result people’s discretionary spending for baseball was drastically reduced.

At the same time Dodger attendance was on a steady decline going from 1.8 million in the late 1940s to roughly 1.1 million right before the team left for Los Angeles in 1958. This ate into the team’s profitability and O’Malley’s answer was a new ballpark. By the mid-1950s Ebbets Field was located in a neighborhood rife with vandalism, in fact New York Daily News sports reporter Dick Young stated that O’Malley had told him “the area is getting full of blacks and spics.” The ballpark itself was in bad need of refurbishing as toilets didn’t work, too many seats were behind support beams, and seating was only 32,000 compared to 70,000 at Yankee Stadium and 54,000 at the Polo Grounds. O’Malley’s solution was to build a new ballpark.

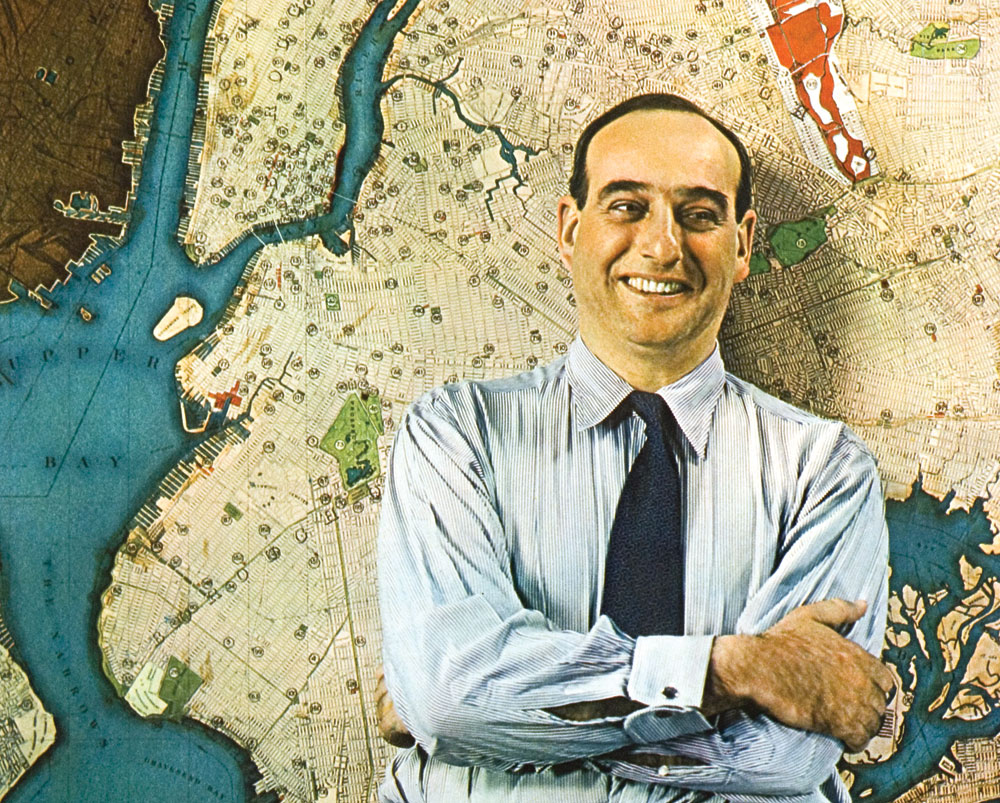

(Robert Moses)

McCue delves into the role of Robert Moses, who was Long Island State Commissioner and the head of the Triborough Bridge Authority and one of the most powerful men in New York. As O’Malley pushed for a new stadium in Brooklyn, Moses became the main roadblock to his vision as he was clear that a baseball team could not use public funds set aside for slum clearance, even if it were part of a larger project that was involved in improving the neighborhood and creating public housing – throughout negotiations over the next few years, Moses would not change his mind. It is clear from McCue’s discussion; Moses did not like O’Malley, which played a major role in their talks. O’Malley tried a number of scenarios to break the impasse but got nowhere. Moses would offer the future site of Shea Stadium in Queens, but O’Malley would not leave Brooklyn. Further impacting talks were Mayor Robert Wagner who never believed that baseball was a priority.

McCue delves into the weeds as he first recounts negotiations with New York officials and then moves on to discuss talks with Los Angeles businessmen and politicians. In both cases the main issues centered on a site for a new stadium, cost of construction, taxation, infrastructure costs, leases, and ancillary aspects including mineral rights, and recreation areas and who would be responsible for paying for these items. What emerges is personality conflict as many involved had their own agendas, but if one is looking for who to blame for the move apart from O’Malley a great deal falls on the people of Brooklyn whose attendance at Dodger games declined precipitously over the previous decade.

(Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax)

One of the most important questions McCue raises is when O’Malley made up his mind to move the Dodgers to Los Angeles. There is no conclusive answer be it after the 1956 World Series, Spring Training 1957, or at some point in negotiations with New York officials. The answer to the question probably depends on your opinion of O’Malley and the process that resulted.

Once the decision was reached to move the team O’Malley’s biggest problem was where the Dodgers were going to play. Wrigley Field, which he purchased was too small with little parking, the Los Angeles Coliseum was too large, and its configuration was not conducive for baseball to the point the Rose Bowl in Pasadena was considered. The key to negotiations was the Los Angeles Coliseum Commission and Los Angeles City Council member, John Holland, who opposed the move and did his best to postpone any construction after a deal was struck with numerous lawsuits and slow walking approvals for construction.

(Los Angeles Coliseum)

One of the most interesting aspects of the process was how the Coliseum would be retrofitted for baseball – not an easy task as a new field needed to be created, more comfortable seats added, reduction in capacity by 10,000, and the cost of renovations. A key person in all aspects of the move was Harold Parraott who joined the Dodgers in 1943. Officially, he was traveling secretary, but his duties included much more as he was in charge of attendance receipts while on the road, needed to know baseball, the newspaper business, and had a knack for figures – Parrott met all of these qualifications.

McCue’s work is more than a biography. It is an intricate portrait of the Dodger owner, but it is also a unique description of the inner workings of the Dodger organization focusing on decision making relating to finally deciding to leave Brooklyn and the myriad problems that developed in Los Angeles including the economics and politics involved. The role of Buzzy Bavasi and Branch Rickey stand out as McCue takes the reader through the history of the Dodgers. But importantly, the author provides a history of Chavez Ravine, the final site for the new stadium, and all the roadblocks that were created to prevent its completion. Once the site was chosen O’Malley had to deal with a referendum on the contract with Los Angeles authorities which would produce a “holy alliance” between groups of various parochial interests who wanted to stop construction. C. Arnholt Smith, the owner of the Pacific Coast Leagues, San Diego Padres financed the opposition, and a fascinating political battle emerged led by John Holland on the conservative side, and Roz Wiener, a liberal on the Los Angeles City Council. The result that a stadium that was to cost around $10 million would rise to $16 million.

(Dodger Stadium, Los Angeles, CA)

In the end O’Malley becomes a towering baseball figure bringing baseball to the west coast, moving his own team but convincing New York Giants owner, Horace Stoneham to move his team to San Francisco. O’Malley’s actions fostered a new sense of unity and identity for Los Angeles which had the reputation of being “72 suburbs in search of a city.” McCue presents a nuanced account showing O’Malley as a shrewd and daring businessman who saw the future of baseball differently than other owners. The narrative fosters a well-researched and even handed account of a man who could be compassionate and generous but also mean-spirited and insensitive.

Paul Dickson’s review in the April 4, 2014, Wall Street Journal captures the essence of the man and what he accomplished: “The real insight of Mr. McCue’s book is that O’Malley was a man who embraced risk and adapted well to new situations. In the late 1960s, as the players union gained in strength under the leadership of Marvin Miller, the adversaries became friends. ‘He is the one baseball owner I respect,’ said Miller. ‘O’Malley is a hard, realistic businessman who is part of this century and who does not pretend that baseball is something it isn’t.’ While other owners saw their battles with Miller and his union as a test of their manliness, O’Malley approached the fight over player salaries more practically. His negotiations with Miller were conducted with civility and what Miller termed ‘the cut-and-thrust between two New York boys—even if many of the fans in their home city still hated at least one of them.”

(Ebbets Field, Brooklyn, NY)