(Lt. Colonel Evan Carleson)

There have been many exceptional people throughout history. People who emit bravery, compassion, and genius whose impact on others is immeasurable. Many of these people have been somewhat anonymous historically. One such person was Major Evans Carleson the subject of Stephen R. Platt’s new book; THE RAIDER: THE UNTOLD STORY OF A RENEGADE MARINE AND THE BIRTH OF U.S. SPECIAL FORCES IN WORLD WAR II.

As the book title suggests Major Carleson made many important contributions as to how the American military conducts itself. A career that spanned fighting the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, and the Japanese in China, the Makin Islands, Guadalcanal, Tarawa, and Saipan saw him implement combat tactics that he observed and studied while watching the Chinese Communists engage Japanese forces in the 1930s. The type of fighting is framed as “guerilla warfare,” which would be developed by Carson’s battalion that would be the precursor of US Special Forces known as “the Marine Raiders.”

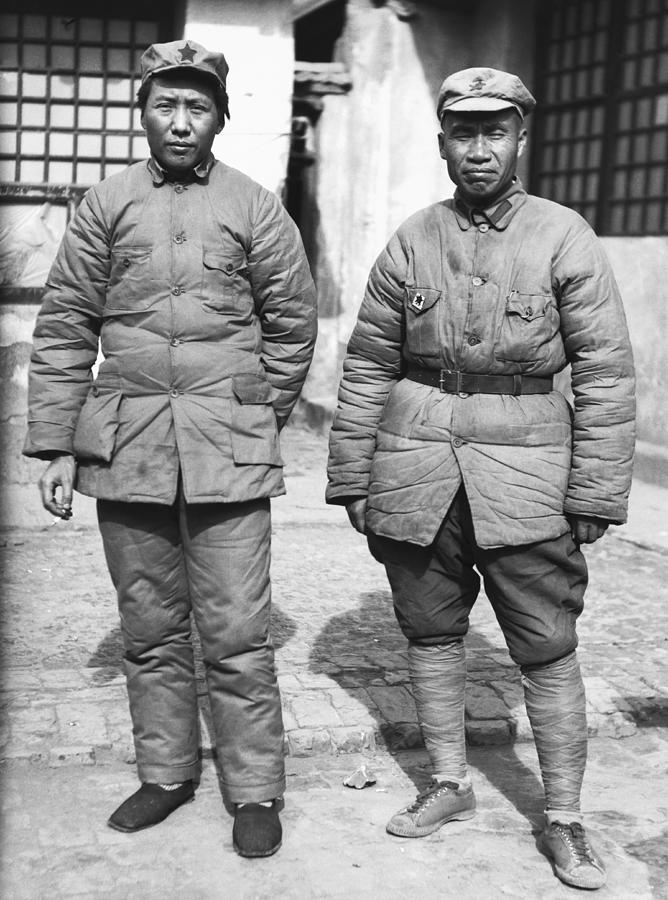

(Mao Zedong and Zhu De)

According to Platt, Major Evans Carleson may be the most famous figure from World War II that no one has ever heard of. He was a genuine hero whose life was full of contradictions, and he would wind up disowned by his service, pilloried as a suspected radical, and forgotten in the postwar era. Platt makes a number of astute observations, perhaps the most important being Carleson’s repeated warnings not to allow the wartime alliances in China to collapse. Today, US-Chinese relations are in part hindered by events at the end of World War II – something Carleson saw coming.

After reviewing Carleson’s early life and career Platt places his subject in China for the first time in 1927 where he would carry out his lifelong ambition to make a difference in that theater. Carleson would spend the next fifteen years observing the Communist Chinese, promoting democracy, fighting the Japanese, developing a philosophy of warfare which rested on a non-egalitarian approach to training men and leading them in combat. Carleson was a complex individual, and like many people he had his flaws as well as his strengths. On a personal level he had difficulties devoting himself to family life and was happier away from his wives and son, than trying to work on his familial relationships. On a professional level he was an excellent leader of men as his approach was to have the same experience as his men in the field which led to success on the battlefield.

(Chiang Kai-Shek)

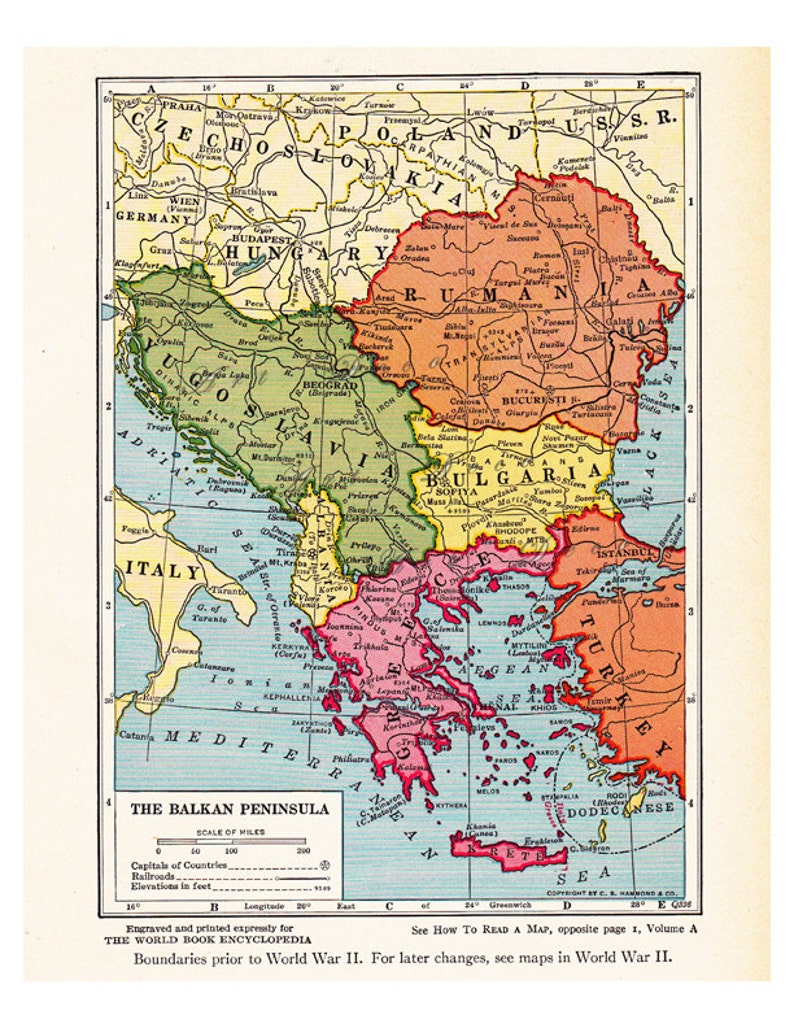

It is obvious from the narrative that Platt has a firm command of his subject. He successfully integrates the flow of Chinese history from the late 1920s through the Second World War and the immediate post war era. Platt’s commentary and analysis dealing with Chinese Communists and Kuomintang relations, Chiang Kai-Shek’s authoritarian leadership, the strategies pursued by the Japanese and the United States are well founded and based on intensive research. This allows the reader to gain a clear picture of what Carleson faced at any given time from the “Warlord Era” in China in the late 1920s, his meetings with Communist officials, particularly Zhu De whose combat strategies became the model for what Carleson created with his Marine Raiders, and events on the ground, and other important personalities he interacted with.

Platt is accurate in his comments pertaining to the balance of power in China. He introduces the Soviet threat in the region as Joseph Stalin supplied Chiang Kai-Shek’s forces throughout the 1930s, reigning in the Chinese Communists as he wanted to develop a buffer to thwart any Japanese incursions on Russian territory. The Soviet Union financed the reign of Sun Yat-Sen and continued to do so with Chiang Kai-Shek. Stalin also forced the Communists to work with the Kuomintang and create a “United Front’ against the Japanese, a strategy that Carleson supported. Carleson’s influence on American policy toward China and Japan was enhanced because of the special relationship he developed with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his son James who was his executive officer and helped create the “Marine Raiders.” A case in point is when Carleson finally learned that the US was supplying oil, weapons, and other resources to Japan to use in China, he helped convince FDR to embargo these items.

In examining Carleson’s approach to the Sino-Japanese war after he was appointed to be China’s Marine 1st Regimental intelligence officer in 1927, Platt correctly points out that many of his views were formulated because of his closeness to Chiang Kai-Shek, a man he admired despite his authoritarian rule. Since he was getting his information from one source he seemed to follow the Kuomintang line. This will change as he is permitted to imbed himself with Communists forces fighting Japan and his “special relationship” with Zhu De who commanded Chinese Communist forces.

(Agnes Smedley)

Platt will spend an inordinate amount of time tracing his subjects ideological development and personality traits. He stresses Carleson’s need to improve. After reading Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ideas as a young man, he becomes a convert to the concept of “self-reliance,” which he intermingled with the concept of “Gung Ho,” or working together which he learned from Zhu De. He pursued a lifetime goal of educating himself and he always seemed to crave a literary career. An important source that Platt makes great use of are Carleson’s letters to his parents where he relates his beliefs concerning the China theater and his own command career which allows him to develop analysis of his subject and the world with which he was involved.

Carleson developed many important relationships during his time in China. Obviously, Zhu De was seen as a model for conducting war against the Japanese, but others like Edgar Snow greatly impacted Carleson. Snow also had access to Chinese Communists leaders and wrote RED STAR OVER CHINA and including in part using Carleson’s intelligence work that the Chinese Communists were not like they had been described in the media. He argued they were friendly, not hostile and open to democracy in the short run, but we know that was Mao Zedong’s strategy before the socialist revolution would emerge. Snow argued that they were well organized, open to an alliance with the United States, and most importantly were not in the pocket of the Soviet Union. Carleson and Snow developed an important relationship intellectually and personally and Carleson agreed with most of Snow’s conclusions.

Platt is a master of detail and is reflected in what Carleson experienced meeting Mao and observing Chinese Communist military strategies. If you explore Zhu De’s approach to training his forces, which he argued were at least as psychological and moral as it was physical, we can see how Carleson mirrored that approach. Apart from Mao and Zhu De, Platt introduces a number of different characters that impacted Carleson’ s life. One in particular is fascinating and had influence over Carleson – Agnes Smedley. Smedley was a left leaning journalist who developed a strong relationship with Carleson, in fact they fell in love with each other, but according to Platt they were never lovers.

(These Japanese prisoners were among those captured by U.S. forces on Guadalcanal Island in the Solomon Islands, shown November 5, 1942).

Carleson was exposed to Japanese military tactics in China and developed ideas as to why Japan could never be totally successful. They had the antithesis of military structure from that of Carleson. He believed the Japanese would fail because of their hierarchical military structure and were extremely vulnerable to surprise attacks and unexpected situations. He further believed that Japanese were not well trained or allowed to think and act on their own. They were more robotic in their approach when compared to Zhu De. Carleson’s positive views on Zhu De would be openly mocked by higher ups, but no matter what was said he continued to speak his mind in interviews, written articles, and reports to FDR and other officials. He would be admonished and warned not to publicize his opinions, but he never wavered by imparting his views no matter what others thought, i.e., he blamed the catastrophe of Pearl Harbor on America’s privileged officer class who lacked incentives to innovate and improve. He argued “they were fearful of any experimentation that might threaten their appearance of infallibility or diminish their prestige.” In the end his superiors had enough of his popularity, refusal to fit in, blurring the boundaries between officers and enlisted men, and idealistic politics promoting him as a means of taking his “Raiders” command away and giving it to a more conventional officer.

Platt delves into the training of the “Marine Raiders,” and the plans for different operations. The results were mixed as the landing on Makin Island, a diversion the US sought to keep supply lines open to Australia which was not a success, while the amphibious landing at Guadalcanal was seen as a victory over Japan as 488 Japanese soldiers were killed as opposed to 16 Americans – eventually the Japanese withdrew from the island. Part of Carleson’s success resides in the area of post-traumatic stress syndrome. It seems that Carleson’s raiders did not suffer from mental issues related to combat as did others. Platt points out that one-third to one-half of all US casualties were sent home because of mental trauma, while the “Marine Raiders” only had one person sent home.

(A U.S. Marine rested behind a cart on a rubble-strewn street during the battle to take Saipan from occupying Japanese forces)

Platt has not written a hagiography of Carleson as he points out his warts. One in particular is interesting is that he would not take Japanese prisoners of war, he instructed his men to shoot them because they had no way to imprison or care for them but also revenge for what they did to Americans. On a personal level he basically abandoned his wives and his only son for his career and was seen as somewhat inflexible in dealing with higher ups in the military chain of command. Many above him felt he had become a communist because of his association with Zhu De, Agnes Smedley, and his criticisms of Chiang Kai-Shek which would follow him for the remainder of his life as his reputation was destroyed during the McCarthy era as J. Edgar Hoover kept a file on him for years.

If there are other biographies to compare Platt’s work to it would be Barbara Tuchman’s STILWELL AND THE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE IN CHINA , 1911-1945 and Neil Sheehan’s BRIGHT SHINING LIE: JOHN PAUL VANN AND AMERICA IN VIETNAM. One book provides similar reasons to Platt as to why the “United States lost China” after World War II and examines very carefully Washington’s approach to the Chinese Civil War which ended in 1949, the other tells a familiar story why the Vietnam War was such a fiasco. Platt’s work is based on strong research as he was the first historian to receive access to Carleson’s family letters, correspondence, and private journals, allowing him to develop complex personality and belief systems alongside the dramatic events of his life. The result of Platt’s efforts according to Publisher’s Weekly “is a gripping, complex study of a military romantic who mixed ruthlessness with idealism.”

(Japanese expansion in the late 19th and 20th centuries)

Alexander Rose’s review; “The Raider” Review: Evans Carleson Made the Marines Gung Ho, June 6, 2025, Wall Street Journal is dead on when he writes; “Hence Mr. Platt’s superficially disproportionate focus on Carlson and his activities in China before Pearl Harbor and the formation of the Raiders—which was really a capstone to his long fascination and relationships with the Chinese Communists and Nationalists. By the late 1930s, Carlson was regarded as the China expert at home. His reports were circulated at the cabinet level and within the most senior ranks of the Navy department; he even enjoyed a secret, direct line of communication with President Roosevelt.

Yet in some quarters there were concerns that Carlson had, to use a perhaps dated expression, gone native. He had developed a severe case of Good Cause-itis and needed to be reminded, as one analyst commented at the time, that he worked for “Uncle Samuel, not China, the Soong Dynasty, or”—referring to one of the Chinese Communist party’s forces fighting against Japan—“the 8th Route Army.”

These suspicions were not baseless. If Carlson had a weakness, it was that he associated with too many American fellow travelers and idealized the Communists, seeing them as nothing more than slightly zealous New Dealers. He told Roosevelt that Mao had assured him that agrarian revolution, one-party rule and proletarian dictatorship might be on the agenda, but only after a prolonged period of capitalist democracy to guarantee everyone’s individual freedoms..

Similarly, Carlson promoted the astoundingly corrupt Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and seems to have believed that they and the Communists would make a great team to secure China’s independence, once they ironed out a few inconsequential political differences. It was in 1944 that he finally tired of Chiang and wrote him off as a reactionary warlord. The Communist Party was the sole executor of the “welfare of the people,” he judged, and thus America’s natural friend.

One gets the impression from his reports that Carlson was often told what he wanted to hear and saw what his hosts wanted him to see. He never grasped that the insurgents’ interests rarely matched American ones, even when the two forces were temporarily allied against a common enemy. Carlson, in other words, broke the cardinal rule of being an observer: Don’t fall in love with the side you’re backing; they’re fighting a different war than you are.

For a time, Carlson’s views held sway in the U.S.—he was a popular, progressive figure immediately after the war and was set to run for the U.S. Senate representing California—but his career soon began to go wrong. A heart attack ended his political ambitions, and in his final years he was castigated as a “red in the bed.” He died a disappointed man, as his illusions shattered against the hard rocks of reality. But American understandings of China have often been founded, or have foundered, on self-deception, both before Carlson’s time, and since.”

(Lt. Colonel Evan Carleson after Makin Island raid)

(The Zorg, a replica)

(The Zorg, a replica)