I have always been fascinated by the History of the Balkans since I was in graduate school, studying European diplomatic history. There I came across Otto von Bismarck’s 1888 commentary that a future European war would be sparked by a conflict in the Balkans, referring to the region as a powder keg. Two of his most notable quotes illustrate his apprehension: “One day the great European War will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans;” and the “whole of the Balkans is not worth the bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier.” Obviously, Bismarck was correct based on the events of June 28, 1914, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand while visiting Sarajevo which led to the outbreak of World War I.

My interest in the region has not waned over the decades, particularly with the Yugoslav Civil War of the 1990s. Last year my wife and I worked with a wonderful guide on a trip to Portugal and Spain who was from Zagreb. After two weeks of travel and conversation we agreed that a visit to Croatia and other Balkan areas would be a wonderful agenda. Fast forward, my wife and I traveled to Croatia, Sarajevo, and Trieste. Before leaving for our journey due to my inquisitive nature (there is a Freudian term which I will not use) I picked up a copy of Marcus Tanner’s informative book, CROATIA: A HISTORY FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO THE PRESENT DAY which was first published in 1997 and has gone through four printings. The original edition was the first history of Croatia written by an Anglo-Saxon author and is important because of its coverage of Croatian history from Medieval times through its transformation into a modern state with membership in the European Union and NATO. Tanner, a former reporter for London’s Independent newspaper who covered the Yugoslav wars, authored the book to fill in the gaps in understanding the former Yugoslavia and in his view Croatia deserved to be studied separately.

Overall, Tanner describes an area that for centuries has been rife with conflict and external threats. Croatian history is disjointed and experienced many attempts to bring cohesion which usually resulted in failure. The author begins with a chapter on the early Croatian kings exploring how the area was first settled in the seventh century, highlighting its relationship with the Papacy and conflict with Slavs and Hungarians, culminating in the Pacta Conventa in 1102.

Tanner describes how the Hungarians would split the kingdom into north and south. The north was treated as an appendage of Hungary, and the south had its own kingdom. Croatia would be ruled as part of the kingdom of Hungary, and Habsburgs until the end of World War I. However, before Habsburg rule that lasted until the end of the Great War took effect the Dalmatian coast experienced a great deal of political conflict and economic competition among its towns and cities exhibiting a great deal of jealousy between themselves as well as Dubrovnik, which emerged as a dominant commercial center.

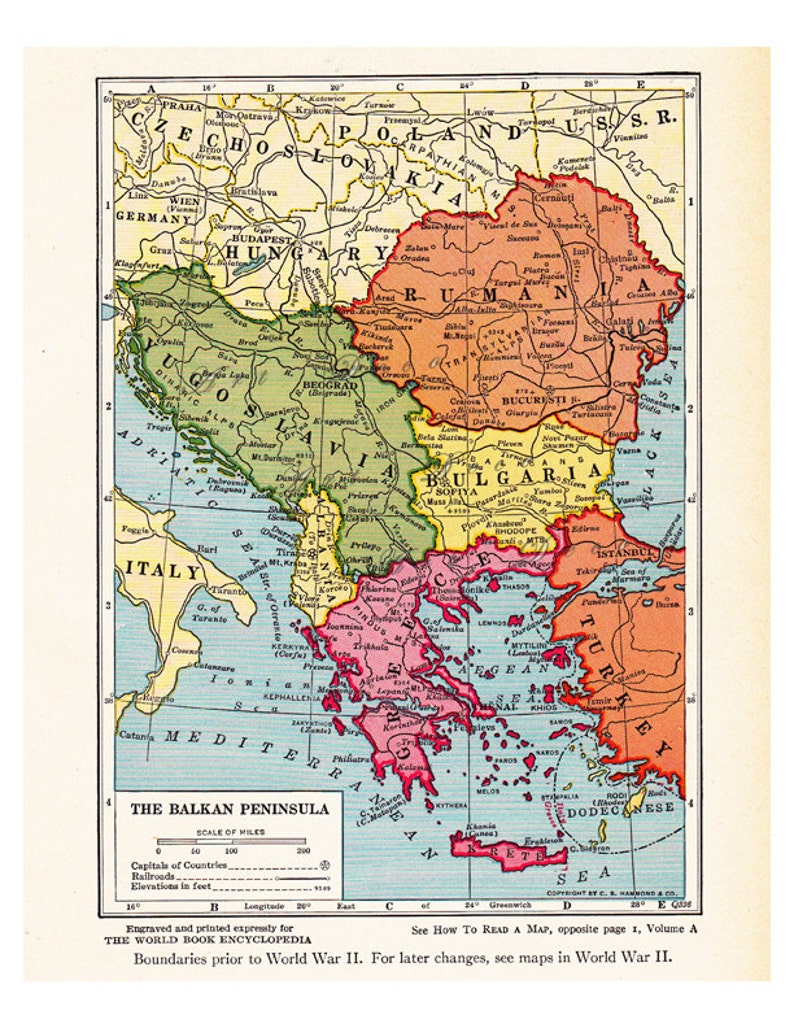

Aside from internal conflict the region also faced tremendous external threats especially from Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Tanner explains Venetian interest along the Dalmatian coast which was focused on the area between Zadar and Dubrovnik. In addition, the Croats were confronted by the Mongols who were beaten back by the Hungarian army in 1241. A century later the Ottoman Turks began to take hold of the region and slowly made their way through the Balkan peninsula seizing Bulgaria, Serbia, Bosnia and by the 1490s it was Hungary and Croatia’s turn at the Battle of Kosovo in 1493; though the fighting continued into the 16th century. With the accession of Suleyman the Magnificent, the greatest of the Ottoman Sultan in 1521, the remainder of Croatia began to fall in the 1520s. As Hungary withered away the Croatian nobles turned to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor who was more interested in crushing Martin Luther.

(View historical footage and photographs surrounding Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand)

Tanner’s monograph is very detailed, and the reader has to pay careful attention to the myriad of names, places, and analysis that is presented. At times, the writing is a bit dense, but that goes with the detail presented. Once Tanner reaches the late 1800s his prose becomes crisper, and my interest piqued as the information is more easily digested as the writing seems to become more fluid. Despite any drawbacks, Tanner does a good job explaining the intricacies of Ottoman inroads into Croatia. One must realize the Croatia of today was split into three parts in the 16th century; Croatia to the north, Venitia along the Dalmatian coast; and Dubrovnik. Each was treated differently by the Turks. Tanner explains the relationship among the diverse groups in the region and concludes that the Croatians were willing to accept Habsburg suzerainty, while Venitia and Dubrovnik were not. The high water mark for the Ottoman Empire in the region was the 1590s, then their interest began to slowly recede.

Tanner is spot on as he describes Ottoman rule over Croatia as “an unmitigated disaster with no redeeming characteristics.” Croatia was Catholic and the Turks had not forgotten the Crusades which led to the almost complete destruction of civilized life, the burning of towns, villages, and the mass flight of peasants. As they laid waste to the countryside their persecution of Roman Catholics was intense and forced many Catholics to convert to Eastern Orthodoxy as the Turks allowed it to become part of the Millet System which granted a measure of religious autonomy. By the early 17th century, the two main noble dynasties in Croatia were defeated and from that point on there was no one to rally Croat nationalism.

(Josip Jelacic)

Tanner is once again correct as he points to the failure of the Ottoman attempt to conquer Vienna as a watershed moment in Central European and Balkan history. It would lead to the end of Turkish control over most of Croatia as the Sultan’s Grand Vizier, Kara Musrtafa tried to renew the tradition of conquest but was unable to defeat the largely unprepared Viennese. The failure was due to the combined army of Poles, Austrians, Bavarians, Germans, and Saxons under the leadership of Jan III Sobieski, King of Poland. It was as a result of this defeat that the Ottoman Empire earned the nickname, “the sick man of Europe.” In 1699 the Ottoman Empire signed a treaty resigning any claims to Hungary or Croatia.

Tanner points to a number of historical figures that greatly impacted Croatian history. One of these individuals is Josip Jelacic, an officer in the Austrian army during the Revolutions of 1848 as well as the Ban of Croatia, another is another 19th century Croatian Ante Starcevic, a politician and writer who believed in self-determination for the Croatian people. He wanted a separate Croatian state, not unification with other southern Slavic states, and came to be known as “the father of the nation.” By the late 19th century other individuals emerged as dominant politicians like Charles Khuen-Hedervary, the Ban of Croatia who tried to Magyarize his country. As we approach World War I Hungary and Habsburg’s discredit themselves in the eyes of Croatians with their political machinations and in 1908 Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia Herzegovina. What follows are the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, a rehearsal for the world war that was to follow. The impact of World War I on the Balkans was significant as the nation of Yugoslavia emerged in Paris with the Treaty of Versailles. From this point on the narrative picks up in intensity but Tanner should devote more time to the events leading up to war, the war itself, and the role of the Croats in Paris after the war.

Tanner succinctly recounts the diplomatic intrigues that produced a unified state in the Balkans and argues that Croats favored the creation of the new country. A constitutional monarchy emerges, but constant ethnic tensions dominate the 1920s as Serbs wanted a centralized state, and Croats favored a federal structure. These issues would dominate the remainder of the 20th century as Croatia opposed unification, favoring regional autonomy.

(Ante Pavelic)

The dominant Croatian politician of the period was Ante Pavelic who created the Ustashe Croatian Liberation Movement in 1929. He would come under the protection of Benito Mussolini who allowed him to train his own fascist fighting force in Italy. Pavelic spent the 1930s in and out of prison, but his movement continued to expand. By March 1940 under his leadership Yugoslavia would join the Axis powers as Pavelic morphed into the dictator of the Croatian state. To acquire credibility among the Croatian people Tanner points to the support of the Archbishop of Zagreb, Alojzije Stepanic, an extremely controversial historical figure. Here Tanner goes into depth concerning the transformation of a Palevic supporter to saving Jews from perishing and being nominated as a “Righteous Christian” after the war.

The actions of Pavelic’s Ustashe during the war would scar Croatia to this day as Pavelic modeled his reign, racial ideas, and militarism on Nazi Germany resulting in the death of about 80,000 people (20,000 of which were children) in concentration camps, the most famous of which was Jasenovac, Croatia’s most notorious camp which I visited during my trip. As with other subjects, Tanner devotes a paragraph to the camp. Pavelic was a firm believer in ethnic cleansing and during the war for the homeland in the 1990s the Serbs accused Croatia of following the program Pavelic laid down decades before.

Tanner seems more comfortable analyzing events after World War II focusing on the rise of Josip Broz Tito who led a partisan movement that defeated the Ustashe. Tito would assume power after the war, setting up his own brand of socialism with a foreign policy that played off the United States and the Soviet Union. Tanner explores this period but does not provide the depth of analysis that is needed in discussing the 1948 split between Tito and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin which was highlighted by extreme vitriolic accusations, one must remember that Tito’s partisans liberated Yugoslavia, not the Russians which was the case in most of Eastern Europe. Tito would institute his own brand of communism and during his reign allowed more and more private enterprise. However, Tito brooked no opposition and ruled with a heavy hand which was the only way Yugoslavia remained united. A.J.P. Taylor, the noted British historian, explained Tito’s success as his ability to rule over different nations by playing them off against one another and controlling their nationalist hostilities.” The problem delineated by CIA report warned in the early 1970s that once Tito passed from the scene the Balkans would deteriorate into civil war.

(Josp Broz Tito)

Tito will die in 1980, and Tanner carefully outlines the deterioration of the Yugoslav experiment which resulted in a number of wars in the 1990s. The two men who dominated the period in the Balkans was Franjo Tudjman, a former communist whose platform rested on Croatian nationalism and by the mid-1990s would prove the most successful Croatian politician of the 20th century. His main adversary was Slobodan Milosevic, a Serbian nationalist who rose to power in Serbia who believed in the creation of a “Greater Serbia” by uniting all Serbs. The fact that tens of thousands of Serbs lived within the borders of other Yugoslav republics was a problem he would try to overcome.

From Tanner’s narrative it is clear that Serbia was responsible for instigating the blood and carnage that tore Yugoslavia apart. Tanner expertly details Slovenian and Croatian independence announced in 1991 and the war that ensued. Many argue that the Yugoslav Civil War was less a bloodletting of one state against another and more like a series of wars that was conducted with mini-civil wars in Croatia and Bosnia. My own view parallels Tanner’s that a series of separate wars took place once Milosevic used the civil war within Croatia as an excuse to redraw the borders of Yugoslavia. Further once the bloodletting ensued the European community and the United States were rather feckless in trying to control and end the fighting. Milosevic pursued what he called a “cleansing of the terrain” of non-Serb elements in Croatia and Bosnia, and Tanner does his best to disentangle the complexity of the fighting and the failure of European diplomacy. Further, after speaking with people in Croatia, the war should not be called, the Yugoslav Civil War, more accurately it should be described as the War for the Homeland.

(Archbishop of Zagreb Aloysius Stepinac)

It is clear that the first war was fought between Serbia and Croatia in 1991 and 1992 and Tudjman seemed to sacrifice a quarter of Croatian territory, i.e.; half of Slavonia and the Dalmatian coast excluding Dubrovnik to the Serbs. However, Milosevic’s hunger for a Greater Serbia and the atrocities that ensued particularly in Vukovar led German Foreign Minister Hans Dietrich-Genscher to manipulate the situation allowing Croatia to emerge victorious with Tudjman emerging as a hero for the Croatian people, but at an unbelievable cost. For Zagreb, it was insidious and horrible for the Croatian people as 6,651 died, 13,700 went missing, 35 settlements raised to the ground, 210,000 houses destroyed…….. People described to me what the war was like and how the Croatian people suffered.

(Slobodan Milosevic)

The second war of the period was the situation in Bosnia in early 1992 between Serbs and Muslims. Within a few weeks of the fighting Serbia controlled 70% of Bosnia and after repeated atrocities against the Muslim community the United Nations voted sanctions, finally the Clinton administration and its European allies employed an arms embargo against the Muslims which Tanner does not really explain. Further, the siege of Sarajevo receives a cursory mention which is a mistake. The siege of Sarajevo and the massacre at Srebrenica deserved detailed exploration.

By April 1993, a third war ensued with Croat-Muslim fighting in Bosnia. Croat actions angered the United States and Germany who helped bring the fighting to an end. In discussing the conflict Tanner presents an interesting comparison of Tudjman and Milosevic which is worth exploring. Finally, the Clinton Administration pushed for peace through the work of Richard Holbrook to produce the Dayton Accords in 1995, but yet again Tanner only provides a cursory mention of the diplomacy that ended the third war. The final war takes place as the 1990s ends in Kosovo whose detail is beyond the scope of Tanner’s narrative.

(Franjo Tudjman)

Tanner’s effort is the first of its kind since the end of communism and the rise of Croatia. Tanner’s work is essential reading for anyone interested in Croatian history, despite the fact that his coverage of the pre-18th century is not as well written and dynamic as the periods that follow. In addition, the book rests on research in mostly secondary sources and there is little evidence of the use of primary materials. However, I found the book a wonderful companion as I explored Croatia, the Dalmatian coast, and Sarajevo and it appears now that Croatia is a member of the European Union and NATO it has tremendous potential for the future.