(Reproduction of a handbill advertising a slave auction in Charleston, British Province of South Carolina)

As the current administration guts the Department of Education, coerces universities to adhere to what they think should be taught in classes, and pressures public schools to rewrite their curriculum to reflect its view of history it is important to examine books that tell the truth about history as opposed to a fantasy that makes certain elements in our society feel better. Banning books, censorship, and curtailing funding is no way to examine our past – something from which we should learn! Just because someone write or says something that is critical of American history does not mean it did not happen or is a threat in our current environment. Remembering our past is a precursor to the present and is a necessity and must be carefully examined as we should learn not to repeat previous errors. It is in this context that Siddharth Kara’s latest book, THE ZORG: A TALE OF GREED AND MURDER THAT INSPIRED THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY must be explored.

Kara’s narrative history portrays his subject with compassion, and accuracy based on exceptional research depicting the harsh realities of the 18th century slave trade involving Africa, the Caribbean, and the American colonies providing lessons we should never ignore. This may come across to some as “wok,” but history is something that should never be dismissed or degraded.

(The Slave Ship (1840), J. M. W. Turner‘s representation of the mass killing of enslaved people, inspired by the Zong killings)

The narrative that Kara presents reads as a work of fiction, but it is not. It is a work that is based on fact and presents an accurate picture of the events he describes. Each chapter ends with a hint of what is to come next. Each important observation is related to what will take place in the future and how it will affect his storyline. Kara provides a very detailed history of the Zorg and its ill-fated voyage, describing in mesmerizing detail the story’s evolution as it embarked on a violent Atlantic crossing. A British privateer captured the Zorg during the Anglo-Dutch War in early 1781, and the ship would sail from the Gold Coast of Africa to Kingston, Jamaica, with its ‘etween deck’ loaded with 442 slaves, including women and children, and a small crew which was not sufficient to care for them. Even the Captain was problematical, a former slave ship surgeon, who had little navigational experience, hired by a rich Liverpool slave merchant.

There are a number of important characters that garner the author’s attention. First, Luke Collingwood, Captain of the Zorg and a former slave ship physician who must have been considered competent since his mortality rate for the crew and slaves was considered below average, however he was not trained in navigation and would become a disastrous choice. William Gregson, underwrote the cost of the Zorg and was considered one of Liverpool’s most prominent slave merchants. James Kelsall, was second in command to Collingwood on the Zorg, and was the only knowledgeable navigator apart from the captain. Robert Stubbs, one of the British governors for the Company of Merchants Trading for Africa (CMTA) was a scoundrel who sold slaves, pocketed the profit, and made decisions out of avarice that would end up in disaster. He was eventually fired but wound up on the Zorg as it made its way to Jamaica. William Llewellin, the captain of the British privateer, Alert, who captured the Zorg, which at the time had 120 slaves. He would capture the Dutch slaving ship, Eendracht, and would add its 124 slaves to the Zorg. Richard Hanley, one of the leading slave captains in Liverpool. John Roberts, another CMTA governor who clashed with Stubbs. Amoonay Coomah, the Ashante King who sold his people into slavery. Olaudah Equiano, captured by slave traders at age eleven, he survived the two Middle Passages having been shipped to shipped to Virginia, served as an officer’s slave on British battle ships. In 1766 he would buy his freedom and later would play an important role in trying to free slaves. Lastly, Granville Sharp who early in career witnessed a scene were a black teenager was beaten, sold, and kidnapped and was outraged. Sharp would work to gain the teenager’s freedom and spend his remaining career as an abolitionist developing arguments against slavery. In addition, Kara introduces a series of English abolitionists who assiduously to end the slave trade in the late 18th and early 19th century.

(The Zorg, a replica)

(The Zorg, a replica)

Kara provides excellent background for the reader to gain a true understanding of what life was like on a slave ship. He points to the difficulties in staffing a ship’s crew. It was a daunting task since men new that Guinea voyages had high mortality rates, offered poor wages, required to complete unpleasant tasks, including guarding and feeding hundreds of captive slaves. Many of the crew hired were impressed or had to work off debts acquired while they were drunk. Most crews that were hired were not experienced enough for a successful voyage.

Kara offers a useful description of the British slave infrastructure in Africa, i.e., forts, factories, supply networks, the dungeons slaves were kept in, and the personalities or governors who were in charge. It is eye opening because the of the horrors the Africans faced even before they were forced to board the slave ships. He makes a series of insightful observations. One of the most important is that once Africans were forced into a dungeon or on to a slave ship they had no concept of what was about to happen to them. The dungeon the British built was indicative of the horrors that awaited the Africans. It was built below the Cape Coast Castle designed to house over 1,000 Africans at a time. Kara introduces Ottobah Cugoano who has written a biographical account of his experience in the dungeon, and his Atlantic crossing on a slave ship. Years later, after obtaining his freedom he would become an important voice in England’s abolitionist movement.

The chapter entitled “Coffles” is an important one as it describes the process by which Africans were either seized by Europeans or sold by Ashante tribal leaders into the slave trade from the interior of the Gold Coast. The inhuman treatment was abhorrent as they marched over 150 miles to the coast with little food and water. Once again they did not know where they were going and what awaited them. To highlight this experience Kara develops the name, Kojo to replicate what an African experienced. Kojo would march for six months as part of this process. Later, he would be forced onto the Zorg and along with the other 442 slaves who would be branded to show ownership.

As Kara writes, “it is impossible to know what emotions the Africans experienced as they passed through the ‘door of no return.’ Was it anxiety, dread, anger, bitterness, hopelessness…perhaps even relief to be out of the dungeon? Most Africans from the inland regions had never seen the ocean before. What impact might first sight of the infinite blue have had on them? Many surely feared they were heading for their doom.

Once Collingswood, Stubbs, and Kelsall overstuffed the Zorg with 442 slaves it was a disaster waiting to happen because the ship’s capacity was around 250. The expected two month “Middle Passage” with a crew of 17 was clearly insufficient to care for their cargo. In addition, supplies would not cover their needs. Once the ship departed for Jamaica on September 7, 1781, a nightmare of dysentery would permeate the ‘etween deck’, the crew would also suffer from scurvy, measles, typhus, measles, and malaria in steerage, as did the captain in his cabin. Kara places the blame clearly; poor planning, a lack of organization and administration led to a shortage of supplies, particularly water, and to exacerbate the situation those in charge of the voyage made numerous navigational errors. The key event occurred when Collingwood became so ill he could not continue in command. He appointed his friend Stubbs, who had experience navigating slave ships, but had not done so in sixteen years, instead of the first mate Mr. Kelsall, who probably would have made better decisions and saved a significant number of lives.

Desperation set in as scurvy became rampant. Kara describes the step by step physical and mental deterioration of the crew and cargo on a ship commanded by Stubbs, who was considered a passenger, in addition to the myriad of poor decisions which would result in disaster. To solve the problem of disease and overcrowding a consensus was reached to throw away large numbers of slaves overboard. By November 29, 1781, 122 individuals were tossed off the ship. Mostly women and children providing sharks with a culinary treat as they were shoved out of a window in the captain’s cabin. Kara is correct that this action was a result of hoping to save enough slaves to recoup as much of a profit as possible once they reached Jamaica, Another possibility was to collect insurance payments for the lost freight! When the Zorg arrived in Jamaica on December 22, 1781, only 208 slaves remained, after roughly 224 slaves were thrown overboard. A year later William Gregsonn would file an insurance claim of 30 pounds per head lost, arguing an ominous situation left the crew with no choice but to throw Africans overboard.

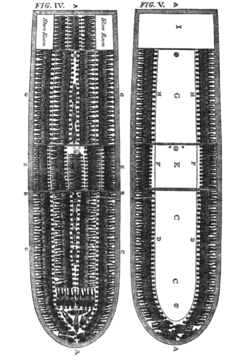

(Diagram of a slave ship from the Atlantic slave trade. From an Abstract of Evidence delivered before a select committee of the House of Commons in 1790 and 1791)

Kara describes the legal battle once the insurers refused to pay as Gregson sued the insurance company in February 1783. The court found for the ship owner resulting in an appeal with England’s Chief Justice believing that the deaths were caused by the crews incompetence, Gregson would withdraw the suit. Finally, Granville Sharpe would publicize the case as a means of forcing the government to abolish the slave trade.

The Zorg reflects a remarkable work of history despite the lack of sources. The author does his best poring over what is available at the Royal African Company’s materials and has reproduced some key documents that highlight his narrative. The most historically important one is an anonymous letter sent to the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser which Kara reprints in full which would light a fire under abolitionist efforts in England that would not be extinguished until all slaves were free. The author should also be commended for integrating the 1783 court transcripts into the narrative which went along way to present the true facts pertaining to the events on the Zorg. Kara’s contribution to the historical record concerning anti-slave movement cannot be denied as he has written a sophisticated account reflecting his moral compass.

(Enslaved Africans in chains marched to the East coast of Africa by Arab slavers)