(The plaque outside explaining the site’s history)

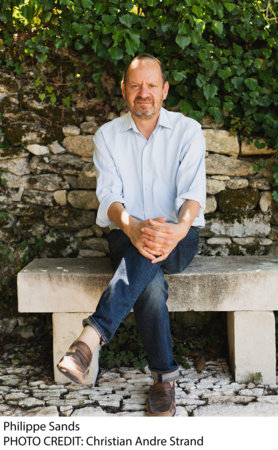

In his latest book, 38 LONDRES STREET: ON IMPUNITY, PINOCHET IN ENGLAND AND A NAZI IN PATAGONIA, British-French human rights lawyer, Philippe Sands completes what he considers a type of trilogy which follows his previous works, EAST WEST STREET and THE RATLINE. The three books are personally motivated studies of how the Nazi genocide of Jews during World War Two has shaped the world’s moral and legal understanding of justice and impunity. As Lily Meyer asks in her review in the October 8, 2025, edition of the Washington Post; “All three books ask to what extent one country is another’s keeper.” But this query becomes obvious in 38 LONDRES STREET which intertwines the story of Walther Rauff, the inventor of the gas extermination vans in which Hitler’s henchmen employed to kill hundreds of thousands of Jews before the extermination camp facilities were constructed, with the extradition trial of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in London in 1998, who after seizing power in 1973 oversaw the deaths and disappearance of over 3,000 people, the torture and imprisonment of over 40,000 victims, and the exiling of hundreds of thousands of Chileans carried out by the secret police he created, the Direccion de Intelligence Nacional (DINA).

Sands organizes his monograph using alternating chapters delving into different aspects of his story that eventually fit together. He focuses on a number of topics and situations. Two of the most impactful are the crimes of Augusto Pinochet and the issue of immunity – does a former head of state have immunity for crimes he committed while in power in a sovereign nation. This leads to a series of chapters highlighting the intimate details as indictments in Chile, Spain, and England favor the extradition of the former Chilean dictator to Spain to stand trial for the crimes he committed while leading Chile between 1973 and 1990. As the narrative unravels a new element is introduced, the role of former Nazi Walther Rauff and his possible complicity in the crimes committed by the Pinochet regime. Sands follows many leads and is very selective as to what he accepts for evidence and concludes that Rauff, in fact participated in some egregious disappearance of political prisoners and their torture.

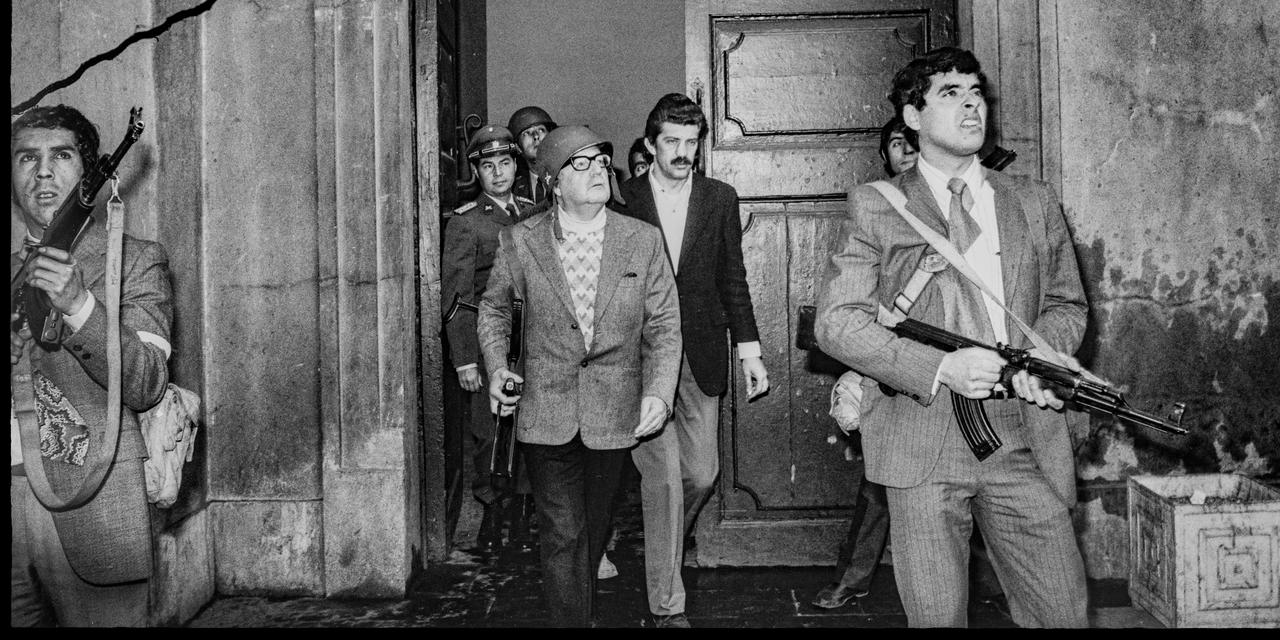

(Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in 1980)

Sands is a prisoner of his own detail as he was actually employed as a lawyer involved in aspects of the extradition hearings, developing relationships with a number of important characters and during his research and interviews learning many troubling aspects concerning his main subjects. This formulates the backbone of his story as sources like; Leon Gomez, Samuel Fuenzalida; and Jorges Vergara are able to link Rauff to Pinochet’s crimes against humanity.

Pinochet was arrested on October 17, 1998, while visiting London to be extradited to Spain for crimes of genocide, torture, and disappearances during his reign in Chile. On September 11, 1973, he played a leading role as Commander and Chief in the military coup against the Socialist government of Salvador Allende. Pinochet was a staunch anti-communist and was supported by Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. The title of the book 38 Londres Street was that the Socialist Party headquarters was turned into a secret interrogation and torture center. Sands immediately describes Pinochet’s crimes focusing on the murder of Orlando Letelier and other assassinations within Chile and abroad, in addition to an abusive prison system that encompasses the entire country highlighted by torture and beatings as more and more people kept disappearing.

Pinochet ruled Chile until he stepped down in March 1998 and became a Senator for life which gave him complete immunity as a parliamentarian, from legal proceedings in Chile. As we will see, the immunity issue dominates the narrative but was only applied for crimes proven after 1998 not before. By October 1998, Juan Guzman, a prosecutor in Santiago was investigating Pinochet’s personal role in allegedly authorizing the “Caravan of Death” operation where 97 people were assassinated across Chile organized by Pinochet. The dictator was protected by the Amnesty Law he signed in 1978 for this and other crimes.

The role of Henry Kissinger and the Nixon administration is important, and I wish Sands could have devoted more time to this aspect of the story as the then NSC head told Pinochet, “I am very sympathetic to your efforts in Chile, we wish your government well…..You did a great service to the west in overthrowing Allende.” It appears Kissinger gave Pinochet card balance to murder Orlando Letelier. On 21 September 1976, the former Chilean diplomat and outspoken opponent of Pinochet, was assassinated in Washington, D.C by a car bomb planted by agents of the Chilean secret police (DINA) as part of “Operation Condor.” Declassified U.S. intelligence documents indicate that Pinochet personally ordered the assassination,] which was intended to eliminate a leading voice of Chilean resistance and disrupt international opposition to his regime. Sands explores those responsible as a deal was made preventing any extraditions to the US.

(Salvatore Allende’s last speech during 1973 coup)

Once Pinochet arrived in London in 1998 he made himself a legal target. Sands’ access to the many major players who sought Pinochet’s extradition is a key component of the book and what separates others who have mined this topic. Sands knew Juan Garces, a Spanish lawyer who prepared the legal work for lawsuits brought by the families of Pinochet’s victims, and Carlos Castresona, the Madrid prosecutor who brought charges against Pinochet applying universal jurisdiction as the basis for his cases for international crimes committed in Argentina – terrorism, torture, and genocide. Castresona sought to establish a legal precedent by going after Pinochet.

Interestingly, the case was personal for Sands as learned he was a cousin of Carmelo Soria, a Spanish-Chilean diplomat assassinated on July 16, 1976. He was a member of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1970s and was murdered by Chile’s DINA agents as a part of “Operation Condor,” as he and his wife were friends with Salvatore Allende. Sands provides the details of the later prosecution of agents for Soria’s murder through the Madrid legal system, and it came down to England’s extradition of Pinochet to Spain which dominates the narrative throughout. Sands had access to the participants and came in possession of a treasure trove of documents. The case would go back and forth as English courts took over since he was in London for medical treatment. At times, the courts ruled that he should be extradited as he was well enough to stand trial. The case involved parliamentary courts led by the House of Lords, Home Secretary Jack Straw and even former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The ultimate result was Pinochet would walk free claiming he was too ill and enfeebled to travel to Spain. Upon his eventual arrival in Santiago, he seemed in the “pink of health.” The question was why he was released. Sands’ research points to a complex deal between England, Spain, Chile, and Belgium that allowed him to return to Chile.

(Walther Rauff in 1945)

The other major component of the narrative is the role of Walther Rauff, a former Nazi who was mentored by Reinhard Heydrich who tasked him to develop vans to be used for gassing people on the eastern front. At the end of the war Rauff would wind his way through the labyrinth set up for Nazi’s to escape Europe and would eventually arrive in Ecuador where Sands provides evidence of his acquaintance with Pinochet, and then Chile. Rauff would be arrested in December 1962, and Sands cites evidence of his nefariousness from documentation of the Eichmann Trial going on in Israel. He soon became a target of the Mossad and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, but Rauff who was working for West German intelligence (BND) assumed he would be protected. Because of Chile’s 15 year statute of limitations Rauff could not be extradited, and the BND cut him loose.

Rauff would be put charge of a fishing cannery in Punta Arenas called Pesquera Camelo after the 1973 coup which thrilled the former Nazi who would develop a working relationship with DINA and provided advice on naval matters. Sands spends a great deal of time trying to link Rauff to Pinochet and concludes he was more than a “desk murderer” who pointed out communist targets for death, though other evidence and interviews Sands conducted point to a larger role. For Sands there is a personal link to Rauff in addition to Pinochet. Sands would learn that his mother’s cousin Herta, was most likely one of the thousands murdered in Rauff’s vans, Herta was twelve years old.

Sands takes the reader inside Pinochet’s reign of horror for thousands including DINA’s organizational structure and tactics interviewing perpetrators and victims at Colonia Dignidad an isolated colony established in post-World War II Chile by emigrant Germans which became notorious for the internment, torture, and murder of dissidents during the reign of Pinochet in the 1970s while under the leadership of German emigrant preacher Paul Schafer. Schafer participated in torture of political prisoners, employed slave labor, and procured weapons for Pinochet. Another example of Pinochet’s house of horrors was Dawson Island. After the 1973 Chilean coup, the military dictatorship of Pinochet used the island to house political prisoners suspected of being communist activists, including government ministers and close friends of the deposed President Salvatore Allende, most notably Orlando Letelier and others. Roughly 400 prisoners were kept there at one time or another and were used for forced labor.

(A hall is pictured at Estadio Nacional memorial, a former detention and torture center of the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship, in Santiago, Chile),

According to Samuel Fuenzalida, a DINA operative, Rauff was in charge of Pesquera Arauco, a fishery that had refrigerated vans that transported political prisoners. Fuenzalida saw Rauff at DINA headquarters at least three times in 1974 and was convinced the former Nazi worked for and consulted for the DINA. Sands uncovers further evidence of Rauff’s role in a meeting in November 2022 with Jorgelino Vergara, another former DINA agent who claims Rauff was at the first “Operation Condor” meeting in 1974. He places Rauff at a number of meetings that resulted in torture of prisoners, beatings, and death. Rauff’s fishery plays an important role as they were used by DINA to carry out its torture, disappearances, even turning detainees into fish meal.

What is clear from Sands’ unparalleled research and intimate knowledge of his subject is that there is a link between Pinochet and Rauff who likely worked together through DINA. Further, after spending an enormous amount of time explaining the legalities of Pinochet’s “immunity” fight and extradition, the former Chilean dictator was able to walk away from prosecution of his crimes. By the time of his death on 10 December 2006, about 300 criminal charges were still pending against him in Chile for numerous human rights violations during his 17-year rule, as well as tax evasion and embezzlement during and after his rule. He was also accused of having corruptly amassed at least US$28 million.

Sands describes the proceedings against Pinochet as the most significant criminal case since the Nuremberg Trials as never before had a former head of state been arrested in another country for international crimes. Jennifer Szalai’s October 3, 2025, New York Times review “Getting Away With it,” captures the essence of Sand’s work; “Sands is also a consummate storyteller, gently teasing out his heavy themes and the accompanying legal intricacies through the unforgettable details he unearths and the many people — Rauff’s family, former military conscripts, British legal insiders — who open up to him.

(British Home Secretary Jack Straw)

Beyond the fact that Rauff and Pinochet were socially connected, the links between them are ghostly. “I wondered about proof,” Sands writes at one point. “I wanted evidence, not speculation, rumor or myth.” What he does find is that the two men embraced the deployment of state power to torture and murder human beings, even as each made every effort to deflect responsibility. Pinochet — who issued an amnesty law in 1978 to immunize himself and his government from prosecution — blamed the people below, insisting he could not control their “excesses”; Rauff blamed the people above, insisting that he was only following orders.

There is a measure of hope in this book, but Sands shows that even in the face of overwhelming evidence, justice is never a foregone conclusion, especially when it comes to holding the powerful to account. In the epilogue, a Pinochet confidant tells Sands that the Pinochet Foundation received a check for nearly 980,000 pounds from the British government, made out to Pinochet personally, to reimburse his expenses while he was in London. Pinochet’s critics were aghast, but his lawyer was unapologetic. “That’s the system,” he said.

Lily Meyer sums up well stating that Sands “relays the court battles with precision and restraint, interviewing representatives of both sides and providing an account intellectual enough to nearly seem neutral, though his detailed, careful descriptions of Pinochet’s crimes serve as reminders of both the trial’s stakes and Sands’s own values. The government of Chile, which was democratic and socialist, opposed Pinochet’s extradition on the grounds that “it was for Chile, not Spanish judges or British courts, to deal with Pinochet’s crimes.” Central to Sands’s work, and to “38 Londres Street,” is the conviction that this claim isn’t true. The book convincingly argues that “torture, disappearance and other international crimes [can] never be treated as official acts,” and that international immunity for them dishonors their victims and undermines the very idea of human rights.”