(Mark Twain)

The life of Mark Twain spans the growth and expansion of the United States from a rural economy to an industrial giant as the leading manufacturing country in the world. By 1910, the year of Twain’s death the United States transversed the Mexican, Civil, and Spanish-American wars leading to America’s status as a world power as World War I approached. Twain’s life’s work and commentary provide an excellent perspective and his personal impact on the period. If there was one author who can give Twain’s life justice it is Ron Chernow. Previous biographies by the Pulitzer Prize winning author include, THE WARBURGS, JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, GEORGE WASHINGTON, THE HOUSE OF MORGAN, HAMILTON, AND GRANT. All are deeply researched and are considered among the best works on their topics by historians and critics alike.

However, his latest work, MARK TWAIN does not measure up to previous books, though aspects of it reflect Chernow’s talent. The main criticism of the book centers around an approach that can be tedious, and at times boring. In the first third of the book he gets bogged down in the minutiae of Twain’s life. For example, when Twain and his family travel across Europe he describes each village and city they visit in detail. The same can be said as Twain embarks on the lecture circuit. If one were to prepare a t-shirt of Twain on tour it would list each stop on the back and would probably have earned the author and humorist extra funds to offset his prodigious spending which also leads Chernow into greater details. Later in the narrative, Chernow makes the same error as he provides so much travel detail of the Twain families nine year European exile that a reader might question continuing with the book. Further as Graeme Wood writes in New Yorker, “Chernow is not a literary scholar-he is best known for his lives of American political, military, and business figures-which may explain his relative neglect of Twain’s literary output….the biography contains no new interpretations of Twain’s novels….instead Chernow devotes a hefty portion of his 1039 pages to Twain’s personal tribulations, a depressing series of bungles and calamities starting in the author’s middle age.”

(Olivia [Livy] and Mark Twain)

A useful example of excessive detail surrounds the cost of building his home in Hartford, CT, the acquisition of furnishings and decorations, and later the additions and renovations. This detail is not necessary and can be considered exasperating for the reader and would have saved the publisher many pages of the narrative. The length of the book is also an issue. If one does not possess strong hands or suffers from arthritis holding the book can be a challenge as it totals almost 1200 pages. Perhaps the book could be presented in two volumes to ease the reader’s experience. This may seem nitpicky, and once you arrive at the 40% mark in the book, two of Chernow’s best chapters emerge. The first, encompasses the writing and publication of HUCKLEBERRY FINN, especially Twain’s use of the “N” word, and the second, a chapter entitled “Pure Mugwump,” reflecting his growing political and societal radicalization. From this point on the narrative seems to flow better, and the author does not get as bogged down in as much detail until the last third of the book.

Despite these drawbacks Chernow has written an important work of history which will supersede previous biographies of the man from Hannibal, MO. Twain’s impact on American history cannot be dismissed. Chernow presents a nuanced view of his subject which should stand the test of time as the most impactful work on an incomparable man.

Chernow seeks to capture the essence of Twain (I will use the subject’s pen name throughout as opposed to his given name, Samuel Clemens) describing him as “a waspish man of decided opinions delivering hard and uncomfortable truths.” He held little that was sacred and indulged an unabashed irreverence in most of his work be it lectures, political or social commentary, or his many written articles. According to Chernow, Twain was not a contemplative writer, but a man who thrust himself on to American culture. Twain can be described as a dilettante as he engaged in many vocations; for example, a Mississippi boat pilot, printer, miner, journalist, novelist, publisher, pundit, polemicist, inventor, crusader, and most importantly, an eccentric non-conformist. Chernow delves into each avocation that Twain engaged in and provides the true sense of the man through his experiences and the people that he met.

(Twain with Livy and their three daughters)

Twain establishes himself as a celebrity early on after attempting a number of occupations. Once he became a writer and lecturer he stands out as “he created a literary voice that was wholly American, capturing the vernacular of western towns and small villages where a new cultural world had arisen far from the staid eastern precincts.” This can be seen in the publication of TOM SAWYER and HUCKLEBERRY FINN as he defines a new American literary style which many critics found offensive as he dealt with matters of slavery and race.

Apart from his life as an author Twain pursued many business interests. He would spend a lifetime pursuing hairbrained schemes and failed business ventures which the author reveals throughout the narrative. These business decisions would lead to poor investments which became an obsession as no matter the warning signs, i.e.; with the Paige Typesetter and the publication of THE LIBRARY OF AMERICAN LITERATURE he would continue to see things as a panacea to great wealth. He would spend a good part of his life in debt, and even when he finally emerged from his financial travails, he would try again risking his newfound financial security.

Twain was a complex individual who repeatedly reinvented himself and developed new people, for example; a northeastern liberal, a political and social radical far different from his earlier roots on the Mississippi and his Missouri upbringing. He would engage in many controversial issues, many of which centered around race and slavery. Chernow describes these activities, lectures, and writings that at the time were considered radical including; slavery, reconstruction, religion, monarchy, aristocracy, and colonialism. He also supported women’s suffrage, contested antisemitism, and waged a war against municipal corruption. When confronting Twain’s views, one must realize how far he traveled intellectually from his conservative upbringing in Hannibal to a person who educated himself with an unparalleled intellectual curiosity. Chernow is correct in stressing the duality of Twain’s belief system as it seems he cannot make up his mind if he admires the life of common people and their troubles or his personal drive to identify with and become a plutocrat.

(Clara Clemens c. 1907)

Chernow takes the reader on an intellectual journey throughout the post-Civil War period in American history. By detailing many of Twain’s writings starting with the GILDED AGE and other works we witness his intellectual growth and societal awareness and his intensity when confronting important issues. Twain was horrified how America evolved after the war between the states into a country controlled by big business, burgeoning cities, and what he termed as a “carnival of greed.” He despised the rampant materialism, and the “incredible rottenness” and “moral ulcers” he saw in America. Interestingly as his fame brought wealth, Twain would become a prisoner for his own desire to accumulate affluence and reap the benefits of his earnings which would often lead him to further poor business decisions and the loss of a great deal of money. During his “business” career Twain was stubborn and usually blamed others for his own decisions to the point where he would seek revenge against those he felt wronged him, when in fact they did not.

Chernow does an excellent job describing the courtship and relationship between Twain and his wife, Livy Langdon, the sister of a close friend. Twain remained enthralled with her throughout their marriage despite her health issues and her ability to reign him in. In fact, a good part of the time she held the reins of power within the family, and she would become his chief editor and confidant in all matters and was able to imbue him with social graces and smooth over his rougher edges and personality – in a sense she civilized him! Twain loved his family, and his three daughters would become his audiences and critique a great deal of his work.

(Jean Clemens)

In addition to his celebrity status, Twain wanted to be known as a “thinker,” not just a humorist commenting on American society. He also wanted to be in control of his own writing as he never trusted his publishers and Chernow delves into his difficulties with editors and certain publishing companies. This would lead him to take over the publication and distribution of his works beginning with LIFE ON THE MISSISSIPPI in 1882 and begin his own publishing company, Charles L. Webster and Company in 1884 once HUCKLEBERRY FINN was completed. The company had an auspicious beginning with his own works and the publication of Ulysses S. Grant’s Memoirs, but Twain pushed to publish other Civil War generals works, a step too far and it cost great profits. The silver lining was Twain’s friendship with the former president. Eventually his decision making in terms of what to publish and how to market those items would prove disastrous.

During his long career Twain would undergo a series of intellectual shifts. A useful example despite his desire to join the plutocracy is his realization, reflecting the dichotomy of his thinking that the flame of radicalism burned deep inside him. He even referred to himself as “a Sans-culotte” resulting in the publication of A CONNECTICUT YANKEE IN KING AUTHUR’S COURT. Despite heretical thoughts concerning American society, Twain saw himself as a true patriot who frowned upon European aristocrats as he remarked that “we Americans worship the almighty dollar! Well, it is a worthier god than hereditary privilege.”

(Olivia Susan Clemens)

Chernow delves into all members of the Twain family in minute detail. One of the major themes that percolates through the biography is Twain and Livy’s deep devotion and support for each other. The section that deals with her ultimate death later in the book, and the pages spent describing her ailments and Twain’s search for doctors who could cure her are fascinating, particularly how his “revenge” would fall on those who promised to cure her but failed. Twain and Livey’s three daughters garner a great deal of attention. Chernow looks at each through the eyes of their father, and each individual daughter. Susy, his favorite who was involved with another woman much to the disgruntlement of her parents, was quite ill and when she died at twenty-four Twain was devastated as he was stuck in Europe and unable to return to America in time for the funeral. This would provoke extreme guilt which would stay with him for the remainder of his life. The middle daughter, Jean, a talented young lady would suffer from epilepsy and along with her mother was one of the causes of the families meandering throughout Europe seeking cures. The eldest daughter, Clara, a talented singer and writer who suffered from depression was tied to the family against her wishes to care for her mother and sister. She would grow bitter and Chernow describes a certain happiness when her mother dies, freeing her to a large extent to live her life as she saw fit. Later in the narrative the author spends a great deal of time on the extreme behavioral aspects of Jean’s illness, and her father’s inability to cope with her. Another major character is Isabel Lyons, arguably the woman who would replace Livy’s role following her death. Chernow traces Lyon’s rise and fall as someone who was indispensable to “the king” as she called him and in the end would be hated for her actions against his daughters and her obsession with Twain.

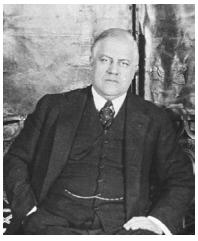

A key figure in Twain’s life was Henry Huttleston Rogers, an American industrialist and financier who made his fortune in the oil refining business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil, a great admirer of the author and humorist. Rogers would repeatedly save Twain from financial ruin, and they would become good friends for the remainder of Twain’s life continuously saving him financially from himself.

Later in the narrative Chernow revisits the evolution of Twain’s thinking; support for women’s rights, funding former slaves, his progression from a southerner to a northerner, developing a pro-plutocracy attitude from a radical supporter of labor and a close friendship with Henry H. Rogers. His intellectual journey will continue later in life, particularly after he returned from Europe and settled in New York as he still could not afford to live in his mansion he and Livy built in Hartford, CT. He would lecture and write against American imperialism after the Spanish-American War and supported Emilio Aguinaldo, the Philippine rebel leader; railed against southern lynchings; spoke in favor of the Boxer Rebellion in China and against Christian missionaries; backed Seth Low the progressive mayor of New York City, among his many causes. This came about after Livy’s death as she was no longer the bulwark against his radical beliefs. As Chernow explains; “no longer content wrap his views in fables and fictions, he resorted to direct, biting prose. He went after things – religion, politics, and patriotism – where citizens felt virtuous and didn’t care to hear contrary perspectives.” He did not regret losing supporters, and in fact he would pick up many new ones as he went after the Romanovs after the St. Petersburg Massacre that led to the 1905 Revolution in Russia, and his diatribes against Leopold II and Belgium’s massacre of the Congolese natives.

(Isabel Lyons)

If there is an aspect of the book that Chernow should have left out is his attempt to a psych historical analysis of a number of characters. The chapter that focuses on Twain’s dreams applying pseudo Freudian principles shows he is out of his depth. The theme can also be applied to what Chernow describes as “Angelfish,” a euphemism for Twain fascination with young girls as the author writes, his obsession was “for a bitter and lonely old man, the Angelfish represented a brighter world.

After reading Chernow’s work I feel like an interlocutor observing the Twain family and learning so many intimate details. There are aspects that could have been treated with greater care particularly Livy’s slow deterioration resulting in her death on June 5, 1904, Twain’s guilt over the death of Susy, and details of Jean’s frequent bouts with epilepsy, Clara’s dissatisfaction with her position within the family, and Twain’s repeated illnesses and health conditions. Chernow does sum it up well by stating; “because of bankruptcy and Livy’s illness, the Clemens family had gone from a happy life firmly rooted in Hartford, to many years of exile.”

A question that must be raised was Twain “fundamentally a dupe or a genius” based on Chernow’s presentation. From my perspective it is a little of both based on my reading of the narrative which is as long as Leo Tolstoy’s WAR AND PEACE. Chernow doesn’t seem to overlook any aspect of Twain’s life, and his error of judgement rests on what he chooses to emphasize . Our image of Twain is of an ungainly, easy going storyteller, but in reality it was a carefully thought out stage persona which does not come across enough in the biography. At the outset Twain’s life reflects a Horatio Alger success tale, but once Twain’s publishing company and typesetting machine go bust his life changes as he must go into European exile as a means of paying off his many creditors, in addition to the deterioration of the health of family members.

Whatever the flaws in Twain’s make-up one cannot question his impact on the period in which he lived and the people he interacted with. As with his subject, Chernow’s work has flaws, but overall if you have the hand strength and perseverance reading the book is an education in itself and worthwhile. Mark Dirdra’s conclusion in his Washington Post review of the book sums it up well; “All of which said, Chernow’s “Mark Twain” does underscore how dangerous biography can be: While knowledge of Twain’s life can enhance our understanding of his writing, the man himself turns out to have been self-centered, loving but neglectful of his daughters, foolishly gullible, something of a money-hungry arriviste and vindictive to a Trumpian degree. Of course, he was also a genius — at least in a small handful of books, perhaps only one really. Was it not for “Huckleberry Finn,” would we really think of Mark Twain as one of America’s greatest writers? I wonder.”

![Richard Nixon-[C]════ ⋆★⋆ ════

[C]“ 𝕋𝕙𝕖𝕪 𝕤𝕒𝕚𝕕 ‘𝕊𝕠𝕟, 𝕕𝕠𝕟’𝕥 𝕔𝕙𝕒𝕟𝕘𝕖’

[C]𝔸𝕟𝕕 𝕀 𝕜𝕖𝕖𝕡 𝕙𝕠𝕡𝕚𝕟𝕘 𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕪 𝕨𝕠𝕟’𝕥 𝕤𝕖𝕖 𝕙𝕠𝕨 𝕞𝕦𝕔𝕙 𝕀 𝕙𝕒𝕧𝕖 ”

[C](https://pm1.aminoapps.com/8046/e5369316bc74864ed586f9055db2050e01c23383r1-236-292v2_hq.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/John-Hay-2700-3x2loc-057ae231b6ee49bca0772e4f8a2426ae.jpg)

![The Education of Henry Adams by [Henry Adams]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41iD6g-2QpL.jpg)