(Smoke rises from the Jajce barracks Tuesday after it was hit by artillery fired by the Yugoslav Army from the hills surrounding Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital. Army artillery pounded Sarajevo on Tuesday, May 5, 1992 leaving the city cloaked in flames and smoke and its streets strewn with corpses)

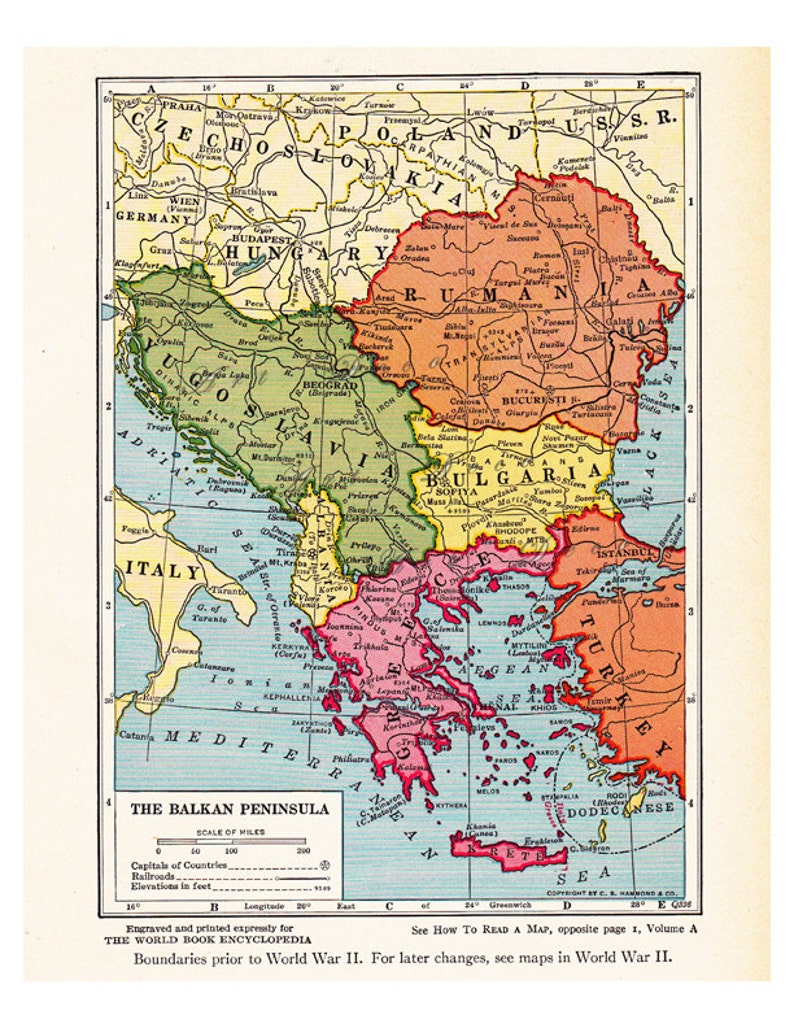

A few weeks ago, my wife and I drove from Dubrovnik, Croatia to Sarajevo, Bosnia after spending a few hours in Mostar. We observed remaining damage from the war for the homeland, a.k.a. the Yugoslav Civil War, and many signs of repairs and rebuilding. The city of Sarajevo which suffered the longest siege in Europe since Stalingrad came across as a vibrant urban area that seems well on its way in recovering from a war highlighted by ethnic cleansing , unfathomable cruelty, and enormous destruction, and random death. There are many exceptional historical works recounting and analyzing the breakup of Yugoslavia and the four separate conflicts that followed, including; the 1991-1992 war between Serbia and Croatia; the 1992 war between Serbs and Muslims; the 1993 war between Croats and Muslims in Bosnia; lastly, the 1998-1999 war in Kosovo.

The horrors of these wars may have receded in the historical memory, however for most of those affected the scars remain as depicted in Jasna Levinger-Goy’s memoir of being on the front lines in Sarajevo in her at times, gut wrenching book, OUT OF THE SIEGE OF SARAJEVO: MEMOIR OF A FORMER YUGOSLAV.

(A 7-year-old girl who was wounded minutes before by mortar shrapnel cries as she is helped into the emergency room of a Sarajevo hospital on August 3, 1992)

The author was born and educated in Sarajevo, in addition to the United States and England. She taught at Sarajevo and Novi Sad Universities and later moved to England during the Bosnian Civil War. Levinger-Goy grew up in a non-religious middle class Jewish family in Sarajevo with parents who survived the Holocaust. During the war 9,000 out of 12,000 Sarajevo Jews perished. Her parents believed in what communism promised and readily accepted the concept of a unified Yugoslavian identity. The author, a non-religious Jew had no issue accepting a life in a socialist country. However, as the years passed Levinger-Goy realized that after ignoring her Jewish origins it took a civil war and fleeing her home for her to accept Judaism as part of her identity. She admitted to herself that her Yugoslav identity was an artificial construct and after registering as a refugee in 1992 in Belgrade her Judaism was brought home to her.

In explaining the origins of the war, she points to the socio-political fabric of Bosnia and Herzegovina as always being extremely complicated, remaining so today. The touchstone of the war came as different political parties emerged by 1991 representing different ethnic groups. One of those parties was led by Radovan Karadzic, a Bosnian Serb former politician who served as the president of Republika Srpska during the Bosnian War. He was convicted of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Under Karadzic the Serb Democratic Party withdrew its representatives from the Bosnian Assembly and set up a Serb National Assembly in Banja Luka. President Alija Izetbegovic reacted on March 3, 1992, proclaiming the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina, mainly a coalition of Croats and Muslims.

(One of 110 children at an orphanage in war-torn Sarajevo looks out from his crib on July 26, 1992. Many of the children lost their parents during the war)

As storm clouds appeared, the author, like many, was mostly in denial. She convinced herself that the coming war had nothing to do with her – it involved Serbs, Croats, and Muslims which she was none of. She realized that in a multi-ethnic country, a unified ideology based on a single-ethnic values were impossible. A war based on ethnic domination and power was the result. One of her primary concerns was the condition of her father who was dying of bone cancer. This would be played out throughout the memoir particularly trying to decide to leave Sarajevo once the war was ongoing and escape to Belgrade. The overriding theme of Levinger-Goy’s memoir is that of identity. First, latching on to her Jewish background to acquire food and an escape, second, she thought of herself as a teacher and academic, lastly, she was not a member of any of the fighting groups. At the outset she thought she could maintain her profession and who she thought she was, later she would realize how naive she was. In the end after living in Belgrade and London she described her new identity as a “British traditional secular Jew of Yugoslav origins!

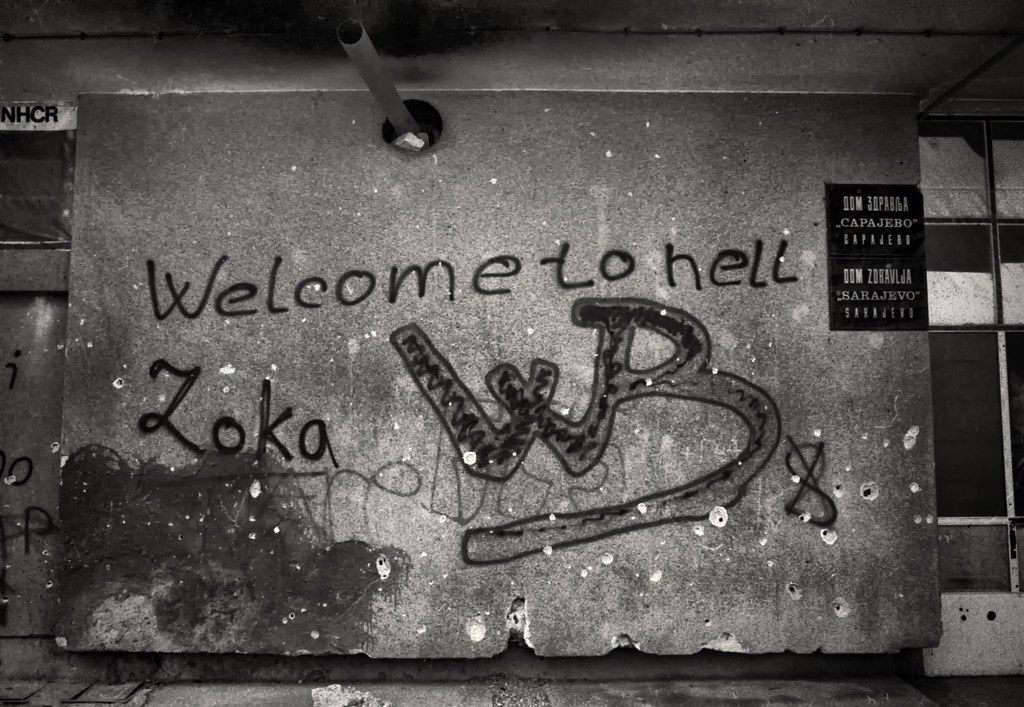

As the fighting progressed it became eerie to be out on the streets with shelling and snipers to avoid constant trips to the shelter in the cellar of her building, then sheltering on the first floor, later in her family’s apartment. Streets were unsafe, but the author clung to teaching, finding food, and staying in touch with friends and relatives. She would become immune to bullets around her – her existence seems to decline in value, except for doing what was best for her parents. The author would go from indifference to denial, to delusions and the final reality that they must leave Sarajevo as walking on glass and cement fragments everywhere was the norm.

(the author)

Sarajevo was surrounded by three impenetrable belts made up of different ethnic militias who made sure no one could come or leave the city. Levinger-Goy spends a great deal of time recounting the daily struggle of life in the besieged city. The crowded cellar, the constant shelling and sniper’s bullets, the search for food and medical care, and the psychological impact on Sarajevo’s residents who were powerless to deal with the randomness of death. After a while the struggle to survive would become the norm as did the fears everyone experienced. Fears they had to overcome on a daily basis.

Perhaps the most evocative chapter in the book is entitled, “Blind Denial,” as the author describes the decision making process and the actual move to leave Sarajevo and travel along the dangerous road to reach Belgrade. High on her list was her father’s health and her mother’s mental state. Reflecting everyone’s desperation she agreed to a marriage of conveniences with the son of a friend in order for him to take advantage of her Jewish identity so he could escape. It is interesting that the Jews and their Jewish Community Center seemed to be in a better position than others in the city – something that feels antithetical to history.

Levinger-Goy’s work will change after leaving Sarajevo she concentrated on family, friends, and survival in Belgrade and eventually London. She morphs into a philosopher as her commentary focuses on the positives and negatives of the human condition. She spends a great deal of time ruminating on the life of a refugee and how people reacted to and treated them. Interestingly, in Belgrade, which she viewed as the capital of her country she was treated as a refugee. It was difficult for her to accept that her country, Yugoslavia, no longer existed.

My only suggestion for the author is that I wished she had spent more time on what life was like inside the siege of Sarajevo. I realize for her it lasted months, but for others it was years. An inside account portraying more of the daily existence was warranted. Over half the book is devoted to her time after the siege focusing on her relationships, her battles dealing with depression, surviving on charity which she abhorred, and her personal demons as she tried to acclimate to a new culture. At times, the book is rather poignant, particularly as she talks about her marriage to the love of her life. A marriage which was sadly cut short when her husband, Ned passed away suddenly. The book is insightful, and its conclusion provides the reader with the hope that Levinger-Goy has overcome her demons and can life as much of a fruitful live as possible in the years she has remaining.

(A Muslim militiaman covers the body of a person killed yesterday during fierce fighting between the Muslim militia and the Yugoslav federal army in central Sarajevo on Sunday, May 3, 1992. Bosnian officials and the Yugoslav army bargained Sunday over the release of President Alija Izetbegovic from military custody)