(Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Joseph Stalin at Yalta 2/1945)

The most frequent question concerning the Holocaust centers on what allied leaders knew about the genocide against the Jews and what they spoke about it in public and private. In previous monographs, FDR AND THE JEWS and OFFICIAL SECRETS: WHAT THE NAZIS PLANNED AND WHAT THE BRITISH AND AMERICAN KNEW Holocaust historian Richard Breitman addresses when these men knew what was occurring in the death camps. In his latest work, A CALCULATED RESTRAINT: WHAT ALLIED LEADERS SAID ABOUT THE HOLOCAUST Breitman shifts his focus as it took until December 1942 for allied leaders to issue a joint statement concerning Nazi Germany’s policy of eradicating Jews from Europe. It would take President Franklin D. Roosevelt until March 1944 to publicly comment on what was occurring in the extermination camps. In his new book, Breitman asks why these leaders did not speak up earlier. Further he explores the character of each leader and concludes that the Holocaust must be understood in light of the political and military conditions exhibited during the war that drove their decision-making and commentary.

Breitman begins his account by introducing Miles Taylor, a Steel magnate turned diplomat representing Franklin Roosevelt in a September 22, 1942, meeting with the Pope. Taylor described the Nazi genocide against the Jews and plans to exterminate millions. He pressured the Pontiff to employ his moral responsibility and authority against Hitler and his minions. In the weeks that followed Taylor conveyed further evidence of Nazi plans to the White House.

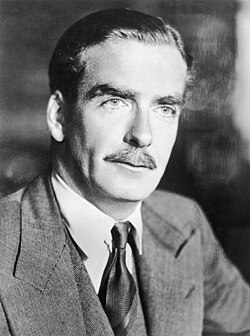

(Anthony Eden, British Foreign Secretary) in 1942

The Papacy’s response was much less than could be hoped for. Monsignor Dell’Acqua warned the Pope that any negative commentary concerning Nazi actions could be quite detrimental to the church, ultimately producing a Papal reaction that it was impossible to confirm Nazi actions, and the Vatican had no “practical suggestions to make,” apparently believing that only military action, not moral condemnation could end Nazi atrocities. It would take until 2020 for the Vatican to open records of Pius XII’s tenure to outside researchers.

Breitman states his goal in preparing his monograph was to discern what “Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin knew about the Holocaust to what they said about it in their most important statements on the subject.” The author’s approach rests on two key avenues of research and analysis. First, the extent to which allied leaders sought to create and mobilize the international community based on a common morality. Second, how allied leaders understood the relationship between the Holocaust and the war itself during different stages of the conflict. Breitman’s account relies on thorough research based on years of archival work, in addition to correspondence among allied leaders, numerous biographies and secondary works on the subject.

Despite the release of most allied documents pertaining to the war, except for Russia which has become more forthcoming since the fall of the Soviet Union there is a paucity of material relating to allied leaders. Further, there is little, if any record of allied leaders themselves addressing the Holocaust in any of their private conversations, though Stalin’s public commentary does allude to Nazi atrocities more so than Roosevelt and Churchill.

It is clear from Breitman’s account that with Hitler’s January 30, 1939, speech to the Reichstag that the Fuhrer was bent on the total annihilation of the Jews, not just pressuring them to leave Germany and immigrate elsewhere. It is also clear that Churchill and Roosevelt were fully aware of the threat Hitler posed to the international order, but were limited in their public reaction to the sensitive issue that a war against Germany to save Jews was not politically acceptable, particularly as it related to communism at a time when anti-Semitism was pervasive worldwide. Fearing Nazi propaganda responses, allied leaders generalized the threat of Nazi atrocities, thereby subsuming Nazi policies to exterminate Jews among a broader range of barbaric behaviors, thereby limiting explicit attacks on the growing Holocaust.

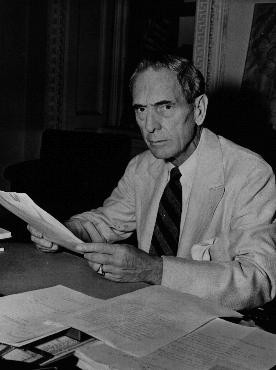

(Breckinridge Long, anti-Semitic State Department official did his best to block Jewish immigration to the United States during the Holocaust)

The author is correct in arguing that had allied leaders spoken out and confronted Nazi behavior earlier it might have galvanized more Jews to flee and go into hiding and perhaps encourage gentiles to take serious steps to assist Jews. No matter what the result it would have confirmed the rumors and stories concerning Nazi “resettlement in the east,” and possibly encouraged neutral governments to speak out and do more.

Breitman’s overall thesis is correct pertaining to why allied leaders did not speak out publicly about the Holocaust, though they did comment on the barbarity of the Nazis. The reasons have been presented by many historians that Roosevelt was very concerned about providing the Nazis a propaganda tool because any comments would be used to reinforce the view that the Roosevelt administration was controlled by Jews and it would anger anti-Semites, particularly those in his own State Department, and isolationists in Congress. FDR reasoned the best way to approach the Holocaust was not to single out Jews and concentrate on the larger issue of winning the war. The faster victory could be achieved, the more Jews that could be saved. This opinion was similar to Winston Churchill’s beliefs.

The author spends the first third of the book focusing on the “Big Three,” and their early views as to what policies the Nazis were implementing in Eastern Europe. Breitman will focus on four examples of public commentary which he analyzes in detail. On August 24, 1941, Winston Churchill made a speech denouncing Nazi executions in the east. He singled out what the Germans were doing to the Russians on Soviet soil, with no mention of the Jews as victims. However, his last sentence read; “we are in the presence of a crime without a name.” Was Churchill referring to the Holocaust? Was he trying to satisfy Stalin? It is difficult to discern, but British intelligence released in the 1990s and early 2000s provide an important picture of what the SS and police units were doing behind battle lines in the Soviet Union in July and August 1941 – mass executions of Jews, Bolsheviks, and other civilian targets. Churchill’s rationale for maintaining public silence regarding the Holocaust was his fear that the Luftwaffe’s Enigma codes that had been broken by cartographers at Bletchley Park would be compromised should he make statements based on British intelligence. It is interesting according to Breitman that after August 1941, Churchill no longer favored receiving “execution numbers” from MI6, fearing that the information could become public. Churchill’s overriding goal was to strengthen ties with the US and USSR and would worry about moral questions later.

In Stalin’s case he made a speech on November 6, 1941, the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 at the Mayakovsky Metro Station. According to Alexander Werth, a British journalist who was present it was “a strange mixture of black gloom and complete confidence.” Aware of Nazi mass murder of Jews, Stalin mentioned the subject directly only once, saying the Germans were carrying out medieval pogroms just as eagerly as the Tsarist regime had done. In a follow up speech the next day, Stalin said nothing about the killing of Jews. Stalin generalized the threat of extermination so all Soviet people would feel the threat facing their country, but at least he mentioned it signaling that subject could now be openly discussed, but Stalin’s overriding concern was to focus on the Nazi threat to the state and people of the USSR and believed that references to the Nazi war against the Jews could only distract from that. After his November remarks he made no further public comments about the killing of Jews for the rest of the war.

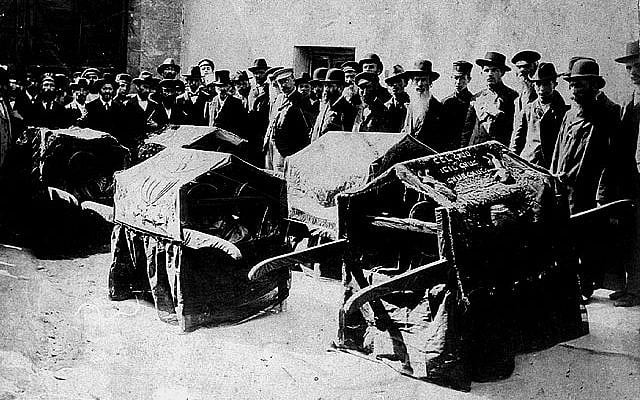

(Jan Karski (born Jan Kozielewski, 24 June 1914[a] – 13 July 2000) was a Polish soldier, resistance-fighter, and diplomat during World War II. He is known for having acted as a courier in 1940–1943 to the Polish government-in-exile and to Poland’s Western Allies about the situation in German-occupied Poland. He reported about the state of Poland, its many competing resistance factions, and also about Germany’s destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto and its operation of extermination camps on Polish soil that were murdering Jews, Poles, and others)

FDR’s approach was to prepare for war and his comments were designed to do so and not say anything that could rile up anti-New Dealers who opposed war preparation. At press conferences on July 31 and February 1, 1941, FDR did not raise the subject of Hitler’s threat to annihilate the Jews of Europe and was not questioned about it. Roosevelt feared any publicity surrounding saving Jews would create greater opposition to aiding the democracies of Europe to fight the Nazis. It took Roosevelt until August 21, 1942, for the president to denounce barbaric crimes against innocent civilians in Europe and Asia and threatened those responsible with trials after the war. He would reaffirm these comments in a statement on October 7, 1942, but in both instances he was unwilling to denounce the Nazi war against the Jews. However, if we fast forward to FDR’s March 24, 1944, press conference, shortly after the Nazis occupied Hungary, the president called attention to Hungarian Jews as part of the Nazi campaign to destroy the Jews of Europe, accusing the Nazis of the “wholesale systematic murder of the Jews in Europe.” Articles written by the White House press corps and government broadcasts were disseminated to a large audience in the United States and abroad.

![Nazi camps in occupied Poland, 1939-1945 [LCID: pol72110] Nazi camps in occupied Poland, 1939-1945 [LCID: pol72110]](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/3482f20c-51c9-4b2e-ab6a-39a202c52f6c.gif)

Breitman dissects a fourth speech given on January 30, 1939, where Adolf Hitler lays out his plans in front of the Reichstag. The speech recounted the usual Nazi accusations against the west, praise for Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, virulent comments and threat against the Jews, and fear of the Bolshevik menace. He was careful not to attack Roosevelt as he wanted to limit American aid. According to Chief AP correspondent Louis Lochner who was present at the speech Hitler reserved his most poisonous verbiage for the Jews as he would welcome the complete annihilation of European Jewry.

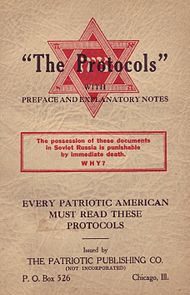

The title of the book, A CALCULATED RESTRAINT is somewhat misleading as Breitman focuses a great deal on events and personalities that may tendentiously conform to the title, but do not zero in exactly on that subject matter. The author details the negotiations leading up to the Nazi-Soviet Pact and its implications for Poland and Eastern Europe in General. Further, he comments on the American and British about faces in dealing with communism. Breitman focuses on the “Palestine question” and its role in Nazi strategy and how the British sought to protect its Arab “possessions,” – oil! Operation Torch, as a substitute for a second in Europe is discussed; the battle of El Alamein and the role of General Erwin Rommel. Other prominent individuals are covered including Reinhard Heydrich who chaired the Wannsee Conference outlining the Holocaust and the Lidice massacre after he was assassinated. Breitman does deal with the Holocaust, not commentary by the “Big Three” as he introduces Gerhart M. Riegner, a representative of the World Jewish Congress and Polish diplomat Jan Karski, who met with Roosevelt, and Peter Bergson who did his best to publicize the Holocaust and convince the leaders to focus more on containing it through his Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe. Another important American official that Breitman spends a great deal of time on is Oscar Cox, general counsel of the Foreign Economic Administration, which included the Lend-Lease Administration who tried to enlist others in the battle against anti-Semites, like Breckinridge Long inside the State Department. Both men played an integral role in making the Holocaust public and trying to convince Churchill and Roosevelt to be more forthcoming about educating the public about the annihilation of the Jews. This would lead to the Bermuda Conference and the War Refugee Board in the United States, neither of which greatly impacted the plight of the Jews. Breitman also includes a well thought out and incisive analysis of the murder of hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews at Auschwitz toward the end of the war.

![SS chief Heinrich Himmler (right) during a visit to the Auschwitz camp. [LCID: 50742] SS chief Heinrich Himmler (right) during a visit to the Auschwitz camp. [LCID: 50742]](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/876bf59a-ccaf-4be4-a190-1ef087a18452.jpg)

(SS chief Heinrich Himmler (right) during a visit to the Auschwitz camp. Poland, July 18, 1942)

Perhaps, Breitman’s best chapter is entitled, “The Allied Declaration” in which he points out that by the second half of 1942 there was enough credible information that reached allied governments and media that affirmed the genocide of the Jews. However, as Breitman argues, the atmosphere surrounding this period and the risks of going public were too much for allied leaders.

It is clear the book overly focuses on the course of the war, rather than on its stated title. The non-Holocaust material has mostly been mined by other historians, and in many cases Breitman reviews material he has presented in his previous books. Much of the sourcing is based on secondary materials, but a wide variety of documentary evidence is consulted. In a sense if one follows the end notes it provides an excellent bibliography, but the stated purpose of the book does not receive the coverage that is warranted.

In summary, Breitman’s book is a concise and incisive look at his subject and sheds some new light on the topic. We must accept the conclusion that the allied leader’s responses and why they chose what to say about the Holocaust must be understood in light of the political and military demands that existed in the war and drove their decision making. I agree with historian Richard Overy that Breitman spends much more time discussing what was known about the murder of Jews, how it was communicated and its effect on lower-level officials and ministers, rather than discussing the response of the Allied big three, which again reveals a generally ambivalent, even skeptical response to the claims of people who presented evidence as to what was occurring.

(Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill at the Tehran Conference, November, 1943)

![Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the SD (Security Service) and Nazi governor of Bohemia and Moravia. [LCID: 91199] Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the SD (Security Service) and Nazi governor of Bohemia and Moravia. [LCID: 91199]](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/bcadb828-8352-4ddb-9350-f28080c6a055.jpg)