(Saddam Hussein)

For years, the United States was involved in a complex relationship with Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. During the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s the Reagan administration provided Baghdad with licenses to acquire certain implements of war, provided intelligence as to Iranian positions, and at the same time engaged with Iran with weapons for hostages. The United States employed Saddam as a counterweight to Teheran from 1979 onward. Later, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, Washington completely altered its policies and organized a coalition to remove Iraq from Kuwait. However, before the war commenced the United States gave false signals to Saddam before he invaded Kuwait which he seemingly misread. Throughout the 1990s the United States backed a series of possible scenarios to overthrow Saddam, but none was successful.

Fast forward to 2003, the second Bush administration under the influence of neoconservatives fostered policies to invade Iraq remove Saddam and achieving control of Iraqi oil and reorienting the balance of power in the Middle East. It is clear today that the result of that policy was to elevate Iran’s regional influence as the Iraq counterweight was removed. The errors fostered by the Bush administration have been a disaster for Washington’s role in the region. How this all came about is the subject of Pulitzer Prize winning author Steve Coll’s latest book, THE ACHILLES TRAP: SADDAM HUSSEIN, THE CIA, AND THE ORIGINS OF AMERICA’S INVASION OF IRAQ.

What becomes clear from Coll’s account is that there was more to Saddam than American politicians and spies could understand – even when the stakes were so high in dealing with him be it trying to uncover his nuclear capabilities, the sellout of the Kurds in northern Iraq, the invasion of Kuwait, and the final cat and mouse game that led to the Second Gulf War. Coll’s research consisted of numerous interviews of the participants in this historical relationship in addition to the availability of Saddam’s secret treasure trove of over 2000 hours of tape recordings of leadership meetings – private discussions – meeting minutes- intelligence files – and other materials. It allows us to see Saddam in new ways, “what drove him in his struggle with Washington, and to understand how and why American thinking about him was often wrong, distorted, or incomplete.” The result is an incisive monograph that details events and decision making in a readable format providing a review of Iraqi American relations since the 1970s. Coll pulls no punches in his analysis, and it is an important contribution to the many works that deal with this topic.

From the outset Coll introduces Saddam’s fears of the Iranian Revolution, his hatred for the Ayatollah Khomeini, his obsession with Israel’s nuclear capability, and his need to develop atomic weapons. He introduces Jafar Dhia Jafar, a British educated physicist who would become the intellectual leader of Iraq’s atomic bomb program who plays a vital role throughout the book as Saddam’s Oppenheimer. Coll’s discussion of the Iran-Iraq war focuses on the motivations of each side and the key role played by American intelligence, weaponry, and licensing. It was clear under the Reagan administration that it wanted to work with Saddam but as we did so we misread his goals. Further Washington’s support for Baghdad fostered deep misunderstand on Saddam’s part as to what they could get away with without American opposition which is the major theme of the book. Throughout the narrative Coll explains the inability of Iraqi and American officials to understand each other from Washington’s refusal to allow Iraq to buy gun silencers to the nuclear policies of both countries.

Coll does a masterful job presenting the background information for Saddam and his family. The relationships within the family exemplified by Saddam’s erratic and murderous son Uday and his brother Qusay, or his son-in-law Kemal Hussein are very important in understanding how Saddam ruled and the impact of his relatives on Iraqi society. Each individual is the subject of important biographical information that include Tarik Aziz, Saddam’s pseudo Foreign Minister, Nizar Hamdoon, close to Saddam who was his liaison to the United States and Iraq’s UN envoy, Ali Hassan al-Majid, better known as “chemical Ali,” who carried out many of Saddam’s most despicable policies, Ahmad Chalabi, a duplicitous character who lied his way to influence CIA policies toward Saddam, and Samir Vincent, an Iraqi-American who worked on the Oils-For-Food negotiations to revive a diplomatic solution between Baghdad and Washington, among others.

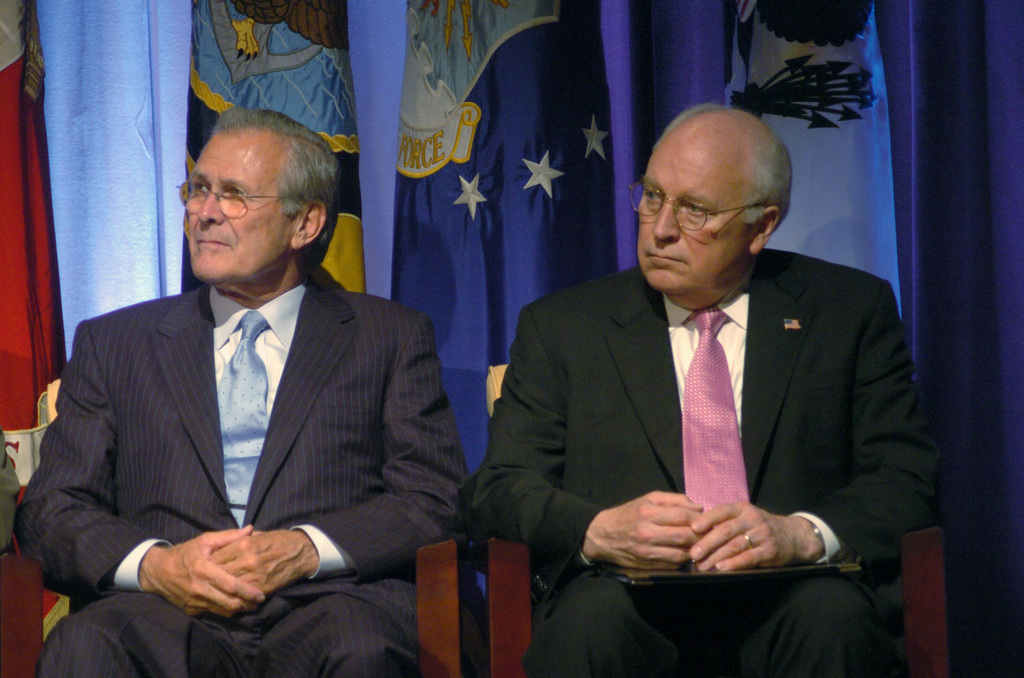

(Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld)

The author raises the question as to why Saddam would risk an invasion when he was aware that he lacked a nuclear option. He would eventually agree to the return of UN inspectors, but it would be too late. The problem as correctly points out is that a decade of an American containment policy had conditioned Saddam to doubt the prospect of a land invasion. Further, since 1991 had threatened military action, but did little. Further he could not fathom why an invasion would take place when he suspected the CIA and other agencies knew he lacked nuclear weapons – an important miscalculation as the Bush administration was bet on war by late 2002, and the task of US intelligence was to find a causus belli to justify an invasion.

Coll is on firm grounds as he describes the many attempts to overthrow Saddam. It is clear that the first Bush administration wanted Saddam to be replaced but refused to engage in assassination. After the first Gulf War, Washington decided not to march to Baghdad and remove him for fear of upsetting the regional balance of power. During the Clinton administration there were many CIA plots involving Saddam’s overthrow from Chalabi’s conspiracies, supporting Wafiq al-Sarranai, an officer close to Saddam, Ayad Allawi, the head of the Iraqi National Accord who led the opposition to Saddam and was an enemy of Chalabi, to members of his dysfunctional family, particularly his demented son Uday.

(Saddam with sons, Uday and Qusay)

A major part of the narrative involves western attempts to uncover and end Saddam’s nuclear program. Coll takes the reader through the “shell game” involving United Nations and the International Atomic Agency’s inspectors to locate evidence of Saddam’s nuclear program. A number of important individuals are discussed including Swedish diplomat Hans Blix, and Rolf Ekeus, the Director-General of the IAEA, David McKay, an American inspector and a host of others. The details of the “cat and mouse” game conducted by the Iraqis is detailed as is the internal dynamic of investigators and their disagreements, including the role of the CIA and American intelligence. They would soon discover that Saddam had a sophisticated bomb program for at least five years without being discovered and Saddam’s capacity to build a bomb was also unknown during that period. It is clear that by the mid-1990s there were no nuclear weapons, but there were biological agents mounted on missiles.

Coll takes the reader through the two Gulf wars, the use of chemical weapons against his enemies, the attacks on Kurdistan, the attempts to remove him from power , all topics that have been dealt with by others, but not in the detail and the perspectives that the author presents. All of this leads to the decision to go to war in 2003 and finally remove Saddam from power and use a new Iraq, dominated by the United States to control the Middle East and its oil resources. In developing this aspect of the book as he does throughout Coll focuses on how Saddam misread American actions and policies toward him. This misreading and/or misunderstandings in the end resulted in his death and a quagmire for the United States that lasted for a decade and even today the United States has difficulties with ISIS terrorists ensconced in Iraq, and a Shia dominated government that our policies helped bring to power.

Coll pulls no punches as he discusses aspects of his topic. A useful example is the relationship between neoconservatives who served during the Reagan administration and Ahmad Chalabi. Coll describes “neocons” as “a loose network of like-minded internationalists who advocated for an assertive post-Cold War foreign policy that would advance American power by expanding democracy by challenging tyranny all around the world.” They sought to undermine the Soviet Union and Saddam advocating human and civil rights as a moral imperative. They would attract the likes of Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld and others who were men who liked ideas on questions as what to do about Iraq. The result was Saddam’s actions invigorated a domestic alliance of American hawk’s laser focused on removing the Iraqi dictator. Chalabi who saw himself as an Iraqi Charles De Gaulle had no following in Iraq and fed numerous lies and conspiracies to the CIA and others and received millions in return – this was the “neocon” darling! Men like Paul Wolfowitz, Zalmay Khalilzad, Richard Perle, and Richard Armitage pushed for war when they realized Bill Clinton would not engage in regime change. American generals thought their ideas were “crackpot.”

George W. Bush’s cabinet read like a “who’s who” of “neocons” with Cheney as Vice President, Rumsfeld as Secretary of Defense, and Wolfowitz as Deputy Secretary of Defense, all backed Chalabi’s “rolling insurgency” plan to overthrow Saddam. Secretary of State Colin Powell who opposed these ideas offered “smart sanctions” – restrict trade directly related to WMD and avoid policies that hurt children and the general Iraqi populations. He felt the military option was not in the best interest of the United States, though he did not rule it out.

(Saddam captured in Tikrit, Iraq)

The question is why did Saddam want to keep the myth of weapons alive when facing steep economic sanctions and threats of war? Coll is clear in his study of Saddam that for the Iraqi dictator a “mutually assured destruction” strategy would offset his fear of an Israeli nuclear attack, an ego which was such that it would provide him with greater security internally and externally, and his misunderstanding of Washington’s capacity to stop him.

Coll’s story presents the long and mutually confusing relationship between the United States and Iraq. It ranges from Saddam’s rise to dictatorial power in 1979, soon after which he started a covert nuclear program, to the 2003 invasion, and his execution in 2006. Along the way we experience a dark chapter in US foreign relations highlighted by the Reagan administration’s turning a blind eye to Saddam’s use of WMD against Iranian soldiers, and under the Bush administration Kurdish villagers, along with CIA policies that enhanced Saddam’s paranoia which led him to defeatist policies as he misread the United States, who at times he perceived to be an ally. All in all, it resulted in what the second Bush administration made, in hindsight across ideological lines a terrible geopolitical mistake which we are still paying for.

What sets Coll’s narrative apart from other authors is his knowledge of Iraqi planning and Saddam’s mindset as it was clear that Bush had made up his mind for “preemptive war”. Coll’s account of the Bush administration’s actions, views, and planning has been detailed by others, but it is his deep dive into Iraqi strategy and the views of Iraqi planners that distinguishes his work.

Charlie Savage in his August 29, 2024, article in the New York Review of Books entitled “A Terrible Mistake” perfectly encapsulates the importance of Coll’s work; “Beyond its value as a history and reappraisal of events, what lessons does this tale of ceaseless misconceptions and miscalculations hold for today? If Iraq was a trap, it was one that a succession of American policymakers clearly did not understand they were getting the country into until extricating it cleanly was nigh impossible. Coll gestures toward the difficulty of understanding dictatorial rulers whose regimes are hard for American intelligence agencies to penetrate and whose own pathologies may also make it hard for them to see the US clearly:

One recurring theme is the trouble American decision-makers had in assessing Saddam’s resentments and managing his inconsistencies. It is a theme that resonates in our present age of authoritarian rulers, when the world’s stressed democracies seek to grasp the often unpredictable decision-making of cloistered rulers, such as Vladimir Putin, or to influence other closed dictatorships, such as North Korea’s.”

:quality(70)/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-mco.s3.amazonaws.com/public/MW56MTM4JNHFLKURY4HPO3BLVA.jpg)