My journey with John Irving began my freshman year in college when I read SETTING FREE THE BEARS. I have enjoyed his quirky sense of humor, his support for those ostracized by elements in society, and the incredible scenes he has created. Perhaps my favorite scene comes from the novel, THE FOURTH HAND, where the main character, a journalist’s ex-wife, employs a lacrosse stick as a pooper scooper for her dog. This unusual tool in a memorable, somewhat bizarre scene, highlights Irving’s style of blending the absurd with profound themes that have carried forth through some of my favorite Irving novels that include THE WORLD ACCORDING TO GARP, THE HOTEL NEW HAMPSHIRE, A PRAYER FOR OWEN MEANY, THE CIDER HOUSE RULES, and TRYING TO SAVE PEGGY SNEED. My journey is very personal as I have taught at a university in New Hampshire, in addition to an elitist boarding school in New England. Further my son played lacrosse at the boarding school and Harvard. In addition, my daughter, son-in-law and two grandchildren are Mainers. So, you can see why I have the affinity for the types of novelistic themes and characters that Irving has created. Now that I am a senior citizen it seems that my adulthood is bookended with Irving’s writings and just when I needed an absurdist fix to deal with the reality of living in a Trumpist world he has produced his latest, QUEEN ESTHER, a book which is wonderful at times, and then disappointing at times.

In QUEEN ESTHER, Irving brings back Dr. Wilbur Larch from CIDER HOUSE RULES after four decades managing adoptions at St. Clouds Orphanage where he is the physician and Director. Larch performs abortions for women who have no alternatives and is as cantankerous as ever. The novel starts out in the early 20th century and revolves around Esther Nacht who was born in Vienna in 1905, the only Jewish orphan raised at St. Clouds. On her voyage from Bremerhaven to Portland, ME her father died of pneumonia aboard ship. Later, her mother will be murdered by anti-Semites in Portland. Dr. Larch realizes that the abandoned child is not only aware that she is Jewish, but also she is familiar with the biblical Queen Esther after whom she was named. Dr. Larch realizes it will not be easy to find a Jewish family to adopt her, soon he is aware that he will never find any family to adopt her.

At the outset, the novel focuses on the Winslow family who date to 1620 arriving on the Mayflower. The Winslow’s reside in Pennacook, New Hampshire, a town which is the home of Pennacook Academy, an independent boarding school for boys founded in 1781. One of its students was James Winslow, a faculty brat and the grandson of the most revered member of the school’s English Department, Thomas Winslow. Since Jimmy’s mother, Esther was an orphan he could not be considered a “blue blood.” The townspeople had difficulties with his mother’s adoption and as Irving develops the novel they were correct as Esther was the caretaker for Thomas and his wife Constance Winslow’s fourth daughter, Honor. Jimmy’s birth was the result of the “pact” between Esther and Honor; Esther would become pregnant and give the child to Honor who detested the idea of birthing a child. So begins a novel that is typical Irving; layered, funny, heartbreaking, and full of the strange humanity he always captures.

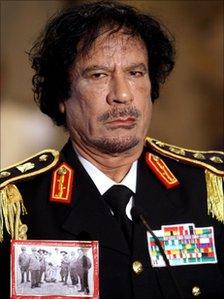

(John Irving in 2010)

The adoption of Esther by Thomas and Constance is important because it allows Irving to delve into societal issues related to abortion. When the Winslow’s set out to adopt a caretaker for their daughter they were clear that they did not want to adopt someone from an orphanage run by nuns or linked to the Christian faith – they could not bear any religious affiliation. After considering a French-Canadian orphanage as too religious they settled on St. Cloud’s where they found Esther, a Jewish child of fifteen who was born in Vienna. As the Winslow’s searched for what turned out to be Esther, Irving presents his pro-abortion views focusing on people who opposed abortion but did not consider the child who would wind up in an orphanage, as it seemed they just wanted to punish the mother. As in all examples of societal issues Irving will present a brief history of the topic and the fact that abortion was not considered illegal from 1620 to the mid-19th century. Irving argues it became illegal as Doctor’s resented midwives who performed them making money at their expense.

Since Esther was Jewish the issue of anti-Semitism soon became the focus of Irving’s characters and thereby his views. He subtly integrates the issue as he believes that New Englanders are covertly anti-Semitic as witnessed by the reaction to Thomas’ lectures on abortion and the adoption of Esther. It is clear that it would be difficult to find parents for Esther because she was Jewish, but since the Winslow’s were a philanthropic, non-Jewish eccentrically non-believing New Hampshire couple, they would be the type open to adopting a teenager like Esther.

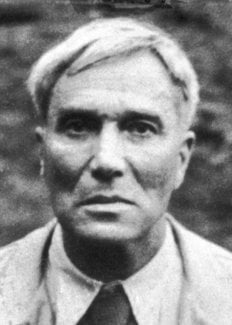

The novel spans the 20th century from 1905 to 1981 and at the outset you get the feeling it is about Esther, but in reality it is mostly about Jimmy Winslow, the son who was the center of the “pact.” Esther herself considered her “Jewishness” as the mainstay of her identity, but was not religious, though she could read Hebrew she did not believe in God. Her main goal eventually was to move to Israel as she was consumed by the exile of the Jews from the land of Israel and the diaspora of the Jewish people. Her outlook on life could be summed up from a quote from JANE EYRE which in true Irving fashion was tattooed between her breasts. She traveled to Europe in 1934 with the goal of getting pregnant to honor the “pact” where she would meet Moshe Kleinberg, a Greco-Roman wrestler in the lightweight class who even had a picture taken with General Paul von Hindenburg when he was President of Germany! Moshe, whose nickname was “the little mountain” would become Jimmy’s father but would never meet him which creates another path for Irving to expound upon as Jimmy has many identity issues because of his background.

As Jimmy matured his grandfather exposed him to literary figures, particularly Charles Dickens that factored into his decision to become a writer. Jimmy believed in his intrinsic foreignness and was determined to see himself as an orphan, no matter how his grandparents tried to raise him. In 1963 we find Jimmy in Vienna seeking his roots and a desire to learn German. Esther will find him a German Jewish tutor who of course he falls in love with. Jimmy’s other issue is the Vietnam War and the draft in the United States. His mother, Honor, sent him to Vienna to meet someone, get them pregnant, keep the baby and in this way he would be draft exempt. If that couldn’t take place she wanted him to wrestle with the hope of damaging his leg also making him draft exempt. In the background everyone wonders about Esther who has gone to Palestine – is she a member of the Haganah, a Jewish defense force or something similar to defend Jews and facilitate their immigration to Palestine. Another plot line that is an undercurrent for Jimmy is his goal of being a novelist, and of course the name of the book is THE DICKENS MAN.

In all subjects that Irving integrates into the novel he has excellent command of the history of the topic. Apart from abortion and anti-Semitism Irving expounds on Jewish history, GREAT EXPECTATIONS by Charles Dickens, films like “From Here to Eternity,” a history of circumcision, the rise of the Nazis, the Holocaust, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Cold War era in general, and Israeli politics and society. It is clear Irving has conducted meticulous research for his novel and should be commended as he immerses himself in his subjects until every detail feels authentic even if it meant visiting wrestling gyms, hospitals or tattoo parlors. Further as he constructs his background history he does it in a concise and meaningful manner where the subject matter just blends seamlessly into the story.

Though the novel seems to focus mostly on Jimmy, the progression of Esther in the background until she emerges at the end of the book is powerful, especially in light of what Israel seems to have become and the arguments put forth by Palestinians and Israelis alike. The reviews for QUEEN ESTHER have been mixed and as usual in interviews Irving does not seem to care what is said about his work. Some have panned the novel but his sarcasm, sense of the absurd, character development, and ability to provide scenes that no one else could create make the book a worthwhile read, and of course along with his unique style of writing.