(Mass grave of Polish officers in Katyn Forest, exhumed by Germany in 1943)

The Katyn forest massacre committed by the Soviet Union occurred between April and May 1940. Though killings took place in Kalinin and Kharkiv prisons operated by the NKVD and elsewhere, the massacre is named after the Katyn forest where mass graves were first discovered by the Nazis in April1943. Roughly 22,000 Polish military, police officers, border guards, intellectual prisoners of war were executed by the Soviet Secret Police, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin issued the orders. Once the Nazis announced their findings Stalin severed diplomatic relations with the London based Polish government in exile because they asked for an investigation by the International Committee of the Red Cross. Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbles realized the publicity value of the find he immediately contacted the Polish Red Cross to investigate but the Kremlin denied culpability and blamed the Germans. The British and their allies, dependent upon Soviet participation to defeat the Nazis, went along with the falsehood. The Kremlin continued to deny responsibility for the massacre until 1990, when it finally accepted accountability for NKVD’s actions and the concealment of the truth by the Soviet government.

At that time Russian president Boris Yerltsin released top-secret documents pertaining to the investigation and forwarded them to Lech Walesa, Poland’s new President. Among the documents was a plan written by Lavrentiev Beria, the head of the NKVD until 1953 dated March 5, 1940, calling for the execution of 25,700 Poles from the Kozelsk, Ostashkov, and Starobelsk prisoner of war camps, and from prisons in Ukraine and Belarus. After the fall of the Soviet Union the prosecutors general of the Russian Federation admitted Soviet responsibility for the massacres but refused to admit to a war crime or an act of mass murder.

(Aerial view of the Katyn massacre grave)

The historical record acknowledges that Stalin was behind the genocidal atrocity and it was part of his larger plan to remove anyone who might conceivably pose a threat to the imposition of future Soviet rule in Poland – “a decapitation of Polish society strikingly similar to Nazi policy in occupied Poland at the same time.” He wanted to eliminate large elements of the Polish elite to remove any potential obstacle to the later imposition of communist rule. For Stalin, Poland was an artificial creation of the 1919 Versailles Treaty that undid the 1772, 1793 and 1795 partitions of Poland between Russia, Prussia, and the Austrian Empire. Because of the Nazi-Soviet Pact of August 26, 1939, Poland would be divided a fourth time between Germany and the Soviet Union. Stalin could retake Russia’s Polish holdings, Western Ukraine and Belorussia without worrying about German opposition. A second line of reasoning for Stalin centers around the Soviet dictator’s knowledge of Adolf Hitler’s intentions. Stalin had read MEIN KAMPF and was fully cognizant of Hitler’s endgame- Lebensraum or “living space” in the east, and how Russia was to be Germany’s “breadbasket.” By invading Poland on September 16, 1939, completing the fourth partition of Poland he would create a buffer zone for the eventual German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. For Stalin it was a defensive measure.

The mystery clouding responsibility over the massacre is the subject of historian and biographer Jane Rogoyska’s book, SURVIVING KATYN: STALIN’S POLISH MASSACRE AND THE SEARCH FOR TRUTH which chronicles how the NKVD worked to reshape the facts pertaining to the massacre blaming it on the Nazis. Planting documents on dead bodies to pursuing a truck full of evidence across Europe, destroying records, to staging incidents in European capitals the Stalinist government left no stone unturned in quashing the truth. Only 395 men survived the massacre who were unwitting witnesses to a crime that theoretically never officially happened. In a striking narrative, Rogoyska brings the victims out of the shadows, telling their stories as well as those of the people who desperately searched for them. In a work of moral clarity and precision, the author does not just supply statistics about another World War II atrocity, but how individuals were sacrificed for no reason and whose memory was lost, a sideshow in the battle between two psychotic and demented dictators.

(Map of the sites related to the Katyn massacre)

At the outset Rogoyska introduces the reader to the prisoners of war and their overseers. She lays out the incarceration process, the paranoia of the NKVD, and the incompetence of the bureaucracy of those in charge. Recounting the interrogation process, attempts to propagandize the Poles, and presenting intimate pictures of the prisoners, the author employs interviews, memoirs, and whatever documentation was available in order to the provide the most complete picture of the personalities and events pertaining to the massacre since Allen Paul’s KATYN: STALIN’S MASSACRE AND THE TRIUMPH OF TRUTH.

Initially the prisoners were taken to three camps, Starobelsk, Kozelsk, and Ostashkov. Rogoyska discusses life in all three camps and focuses mostly on Starobelsk as she follows the lives of Bronislav Mlynarski, Jozef Czapski, and Zygmunt Kwarcinke. They would be among the last group that left Starobelsk and were sent to a transit camp at Pavlishchev Bor in a group of 395 out of 14,800 from all three prison camps. On June 14, 1940, they were taken to the Griazovets camp located halfway between Moscow and the Arctic port of Arkhangelsk.

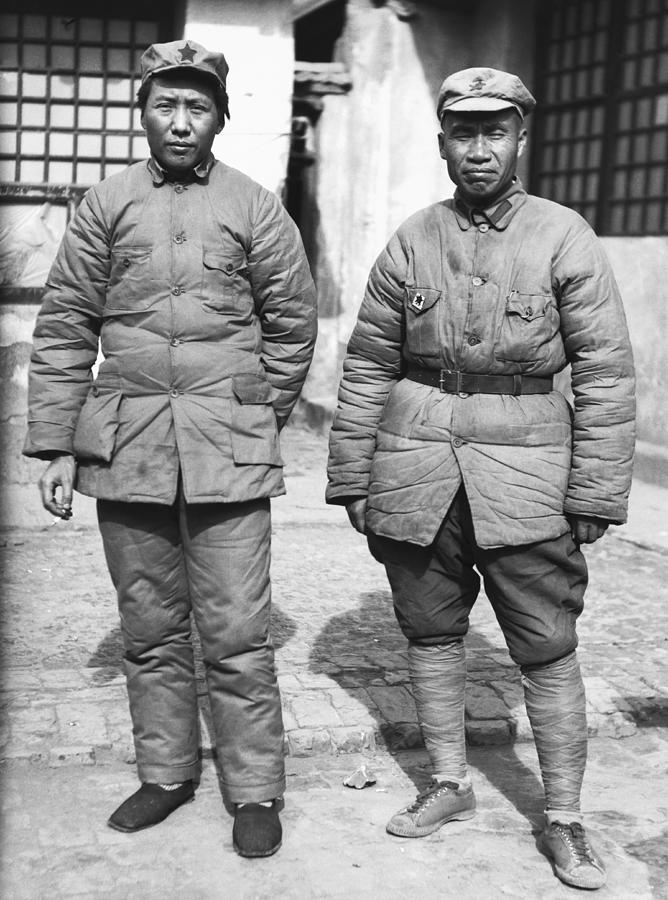

While in Griazovets, Beria, with Stalin’s support, worked to create a Polish Division within the Red Army, a topic that Rogoyska spends a great deal of time discussing. Beria and his henchmen tried to recruit Polish officers to lead it, most refused, but a few from a pro-Soviet group from Starobelsk known as the “Red Corner” agreed. The NKVD was concerned about the officer’s attitudes toward the exiled Polish government in London. While questioning other officers who remained POWs who wanted information about the whereabouts and availability of their compatriots, Beria responded “no, we made a big mistake.” From this phrase the author develops Beria’s guilt in the death of thousands. It would take until May of 1943 for the creation of the Polish 1st Tadeusz Kosciuszko infantry division within the Red Army led by General Zigmunt Berling, an NKVD collaborator. This would satisfy Beria’s goal of a division with a “Polish Face” within the Soviet military.

( Director of the Soviet secret police-NKVD Lavrenty Beria)

During training at Griazovets, the NKVD invested a great deal of time trying to gain the loyalty of the Poles. They created a cultural school employing film, lectures, music, better treatment, etc. to no avail. The NKVD attempt to re-educate these men was an abject failure.

Finally on June 22, 1941, Stalin’s greatest fear came to fruition when the Nazis invaded Russia. The invasion impacted the prisoners in a number of ways. First, conditions at Griazovets worsened as rations were cut 50%, clothing became unavailable, and freedoms were lessened. Secondly, the Polish POWs feared as the Russians collapsed they would be seized and imprisoned by the Germans. Thirdly, a large influx of new prisoners created chaos. Lastly, the London Poles came to an agreement with the Kremlin, known as the Sikorski-Maisky Agreement, restored diplomatic relations between Poland and Russia, instituted an amnesty for all prisoners in Russia, including thousands of women and children. It was decided that General Wladyslaw Andres would command the Polish army after his release from prison on August 4, 1941. The Poles, no longer prisoners, wondered the fate of their comrades – they had no idea that 14,500 of them from the three camps had been massacred.

From this point on Rogoyska explores who was responsible for the deaths of thousands of POWs, who was responsible for their deaths, and how the truth was covered up. Despite the amnesty for prisoners during their arrests they were sent deeper into Russia. These deportations took place between 1940 and 1941 numbered between 1.25 and 1.6 million, though the NKVD argues it “was only” 400,000. The death toll was about 30%.

( Jozef Czapski in uniform, January 1943)

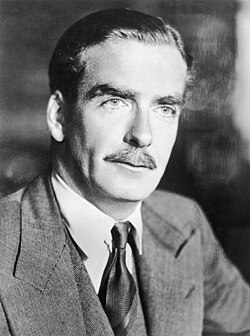

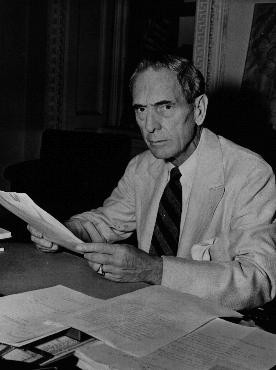

Rogoyska focuses on the major players in her investigation. Generals Anders and Zygmunt Bohusz-Szysk met with Marshal Georgy Zuhkov and General Ivan Pantilov asking for a list of Polish soldiers taken by the Soviet Union. They met six times and meetings were pleasant until the fate of the prisoners were brought up and Zhukov would change the subject and remarked they would eventually be found. Professor Stanislaw Kot, a Polish academic was placed in charge of the prisoner issue by Andres, but he also was stonewalled and got nowhere. His meetings with Andrey Vyshinsky (Stalin’s purge prosecutor in the 1930s) and Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov who offered to assist but claimed the NKVD did not maintain detailed records on the missing officers. Kot knew it was a lie, and the author details the meticulous records the NKVD kept. Rogoyska integrates transcripts of their meetings and Kot grows increasingly angry and frustrated with Vyshinsky’s responses. Molotov wrote General Sikorski in December 1941 that “all Polish citizens detained as POWs had now been released and that Soviet authorities had given them all necessary assistance.”

The author addresses the silence surrounding the missing men that gave rise to theories as to their fate. The most plausible thing was that they had been sent to one of the Soviet Union’s remote regions and had not yet been able to make their way south. Another theory rests on the claim that Polish prisoners were working in the mines and construction of military facilities in the Gulag region of Kolyma in the far east of Russia. Andres put former prisoner Jozef Czapski in charge of investigating the plight of these men and basically took over from Professor Kot. After meeting with Major Lenoid Raikhman, who was in charge of the Polish section at the notorious Lubyanka prison in Moscow who plead ignorance about the fate of the 14,500 officers, Czapski concluded they were probably sent to the remotest parts of the country and very few returned, and even those who made it back could not provide any useful information. Czapski was limited because he was appointed by the exiled Polish government in London and since the British were dependent on their Soviet allies in defeating Hitler they did not want to create waves.

Another key figure in the investigation was Lt. Stanislaw Swianiewicz, a former prisoner in the Kozelek camp and a distinguished professor of economics. The NKVD was interested in him because he had authored a book explaining how the Germans had rearmed. His story is right out of a movie set as the Russians interrogated him, released him, and tried to rearrest him but he escaped. Rogoyska’s chapters on his escapades provide a glimpse into Soviet thinking, the diplomatic game that was taking place between the Polish government in exile, the allies, and the Soviet Union, and Russian duplicity throughout. Swianiewicz was important to the Stalin because he was a witness to Soviet war crimes.

(Andrey Vyshinsky in 1940)

The Soviet smokescreen began in the fall of 1943 after the Red Army retook the Smolensk area. Before the Soviets arrived, the Germans allowed a group of Allied journalists to watch an autopsy prepared by Professor Gerhard Buhtz, the head of Germany’s Army Group Medical Services who pointed out that the bodies were all shot through the back of the head. Not to be out done, the Soviet Union conducted its own investigation headed by Lt. General of the Medical Corps and one time doctor to Stalin, brain specialist Nikolai Burdenko. NKVD operational workers arrived at Katyn in September 1943 under the direction of BG Major Leonid Raikhman whose men proceeded to rearrange the site, swaying witnesses, planting documents on dead bodies to support the charge that the massacre did not occur in 1940, but in August 1941 during the Nazi occupation. After allowing a group of journalists to visit the site, Alexander Werth, British journalist concluded that the evidence was very thin, and the site had a “prefabricated appearance.” He agreed with others that Moscow had committed the massacre. To her credit, the author delves into minute detail of the investigations and the personalities involved who could only conclude based on their findings it was not Germany that was responsible, but the Stalinist regime. She also includes primary source material like the Burdenko Commission report and others that were issued after careful investigations of the site and the exhumed bodies.

(Formal portrait, 1932 Josef Stalin)

The British and the Poles were convinced the NKVD was responsible, but it did not matter as the Soviet Union was needed to defeat Germany, so the allies swallowed their concerns. After the war, the communist government in Warsaw pursued anyone who tried to alter occurrences that would contradict the Soviet rendering of events.

Since the topic of the massacre has fostered a great deal of scholarship it is not surprising that the author does not contain any new revelations. But to her credit her account is lucid and powerful as she recreates the lives of the officers who were artists, scientists, engineers, poets, lawyers, as well as career military men. She chose to examine her topic through the lens of the investigation rather than describing it as it happened which may have been more thought provoking for the reader.

(A mass grave at Katyn, 1943)

![Nazi camps in occupied Poland, 1939-1945 [LCID: pol72110] Nazi camps in occupied Poland, 1939-1945 [LCID: pol72110]](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/3482f20c-51c9-4b2e-ab6a-39a202c52f6c.gif)

![SS chief Heinrich Himmler (right) during a visit to the Auschwitz camp. [LCID: 50742] SS chief Heinrich Himmler (right) during a visit to the Auschwitz camp. [LCID: 50742]](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/876bf59a-ccaf-4be4-a190-1ef087a18452.jpg)

(The General Elżbieta Foundation, ToruńZo, as seen on her student pass, graduated from Poznań University with a higher degree in mathematics)

(The General Elżbieta Foundation, ToruńZo, as seen on her student pass, graduated from Poznań University with a higher degree in mathematics) (The General Elżbieta Foundation, ToruńZawacka (centre) took the nom-de-guerre Zo after being sworn into the Polish resistance)

(The General Elżbieta Foundation, ToruńZawacka (centre) took the nom-de-guerre Zo after being sworn into the Polish resistance) (Getty ImagesThe Warsaw Uprising was the largest organised act of defiance against Nazi Germany during World War Two)

(Getty ImagesThe Warsaw Uprising was the largest organised act of defiance against Nazi Germany during World War Two) (Clare Mulley/A mural depicting Zawacka has been painted on the side of the communist-era apartment block where she lived in Toruń)

(Clare Mulley/A mural depicting Zawacka has been painted on the side of the communist-era apartment block where she lived in Toruń) (The General Elżbieta Foundation, ToruńElżbieta Zawacka crossed international borders more than 100 times as she smuggled military intelligence to the Allies)

(The General Elżbieta Foundation, ToruńElżbieta Zawacka crossed international borders more than 100 times as she smuggled military intelligence to the Allies)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/bb/efbb5d8a-01e8-4e24-b630-b0658ced847c/06b_ce16_wwiiairbattles_c46overthehump.jpg)