(Lech Walesa remains a hero to many Poles for having led the Solidarity movement)

At a time when book bans and censorship has gained popularity in the United States among certain elements in society it is interesting to explore a book that does the opposite. Charlie English’s new work, THE CIA BOOK CLUB: THE SECRET MISSION TO WIN THE COLD WAR WITH FORBIDDEN LITERATURE examines how the CIA used the distribution of books as an overt and covert weapon against the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. The monograph focuses primarily on activists who sought to liberalize Polish government and lessen Soviet influence in the 1980s and the role the CIA played primarily in the background.

The purpose of a book ban is to deprive people of the opportunity to choose or read particular reading material because it does not conform to the beliefs or political agenda of certain groups. Schools, libraries, school boards mare among those that have been targeted by such groups during the last decade or so complaining about certain books as being offensive that have no place in educating children. Books like MAUS by Art Spiegelman and THE HANDMAID’S TALE by Margaret Atwood have been challenged as have been classics like TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, CATCHER IN THE RYE, and THE COLOR PURPLE have been recently placed under the microscope. It is interesting to note that book bans are a tool of authoritarian regimes to block the spread of ideas they disagree with for the general public, so it is fascinating to examine a historical example from the Cold War as the CIA employed manuscripts as a means of winning the battle for the hearts, minds, and intellect of people residing under communist rule in Eastern Europe.

(George Minden)

English’s narrative focuses on the “CIA Book Program,” a covert intelligence operation led by George Minden whose goal was to offset Soviet censorship and misinformation to provoke revolts in Eastern Europe by exposing people of that region to different visions of thought and culture. A classic example is the dissemination of George Orwell’s 1984 of which thousands of copies were made available behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War. This was one of the millions of titles that arrived illegally in Poland, which was just one country in the Soviet Bloc that received great quantities of banned publications. Books arrived by every possible means: smuggled in trucks, yachts, sent by balloon, mail, even a traveler’s luggage. Increasingly, the underground would public homegrown titles, as well as those from foreign publishers. Polish activists argue that the contribution of literature to the revolt against the Soviet Union was a key element in the eventual victory. A major contributor was the role of the CIA which sought to build up circulating libraries of illicit books, and support primarily with funds the burgeoning underground publishing industry in Poland.

There are a number of key figures that English describes throughout his narrative. Perhaps the one that stands out the most is Miroslaw Chojecki, a Polish publisher who was arrested 43 times and treated as you would expect by the Polish version of the KGB, the SB. The description of his internment is right out of Alexsanr Solzhenitsyn’s GULAG ARCHIPELAGO with beatings, isolation, forced feedings, interrogations, and hunger strikes. In September 1977 Chojecki created the Independent Publishing House “NOWa” which constituted the largest publishing house operating outside official communist censorship, becoming its leader. Initially, Chojecki wanted “NOWa” to publish historical books on topics officially forbidden or ignored by the communist authorities, but other oppositionists convinced him to also issue works of literature, including the Czeslaw Milosz and Gunter Grass. In August 1980 he organized the printing of publications of the “second circuit” (as underground press was known in Poland at the time). He was re-arrested but was released and joined Solidarity to free the Polish people from the Soviet grip. In October 1981 he went to France when the imposition of martial law by the government of General Wojciech Jaruzelski occurred. He remained in exile in Paris and published a monthly “Kontakt”, produced films on modern Polish history, and organized support for the underground in Poland, and oversaw the smuggling of books and other written items into Poland. His chief ally and mentor were Jerzy Giedroyc, a Polish writer, lawyer, and political activist who for many years worked as editor of the highly influential Paris-based periodical, “Kultura,” disseminated throughout Poland. Another important figure English delves into is Jozef Czapski who would be sent to Washington to raise funds and support from the United States and would be codename QRBERETTA by the CIA.

(Miroslaw Chojecki in 1981)

Other characters and the roles they played in smuggling books, printing presses, printing materials, etc. into Poland include Helena Luczywo, the editor of the “Mazovia Weekly,” her husband Mitek, Marian Kalenta and Jozef Lebenbaum, Swedish publishers who were very effective smuggling all items needed by the underground from Malmo and Stockholm until they would go a step too far. Each character is explored by English, relating their backgrounds, especially those who had escaped the Nazis, went into exile and returned to Poland. These individuals and the younger Polish generation were all part of the Polish underground movement whether living inside or outside Poland working to overthrow and undermine communism.

English nicely intersperses the history of the anti-communist movement in Poland throughout the narrative. The events of 1980 as the Warsaw regime raised food prices leading to a strike at the Gdansk Shipyard which would provide for the emergence of Solidarity and Lech Walesa as its leader. After what was seen as a victory by the workers, the Jaruzelski regime resorted to an internal coup on the night of December 12, 1981, rounding up thousands of political prisoners in what is referred to as the “Winter War” by Zomo units or Motorized Reserves of the Citizens’ Militia who were empowered by the government and were synonymous with police brutality. Martial law was declared, and the underground had to resort to increased smuggling which English describes in intimate detail as the achievements of 1980 were lost.

One might ask what was the response of the Reagan administration to these events. It moved very slowly, pushed ahead by Daniel Pipes, acting NSC head, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s former NSC head, and CIA Chief William Casey, who was sort of a “cowboy” who always favored overthrowing governments when he could. It took until September 1982 for Reagan to authorize new CIA covert action in Poland, but the remit was small involving funds, and non-lethal aid to Solidarity and other moderate opposition groups to put pressure on the Warsaw regime – it was referred to as “QRHELPFUL.” They built upon the work of George Minden who had developed a long standing book smuggling operation in Eastern Europe, and Solidarity emerged as the nerve center of the opposition. CIA Deputy Director Robert Gates used the money for printing material, communications equipment, and other supplies to fight an underground political war.

(Jerzy Giedroyc, Maison-Laffitte, 1987)

English has written dual history which converges into one. At first, he describes the role of Solidarity figures and the Polish literary underground who were intimately involved with standing up to the Soviet Union and its puppets in Warsaw. Once the Jaruzelski government succumbed to Russian pressure instituting a crackdown in December 1981 the author’s focus shifted to the Kremlin’s goal of destroying Solidarity and its leadership. As far as the CIA’s role throughout the narrative, it was designed to pay for all the clandestine activity institutes by the likes of Miroslaw Chojecki and find ways to carry prohibited equipment across the border.

English highlights many examples of where funds came from to support the Poles. His description of the Ford Foundation is fascinating as they provided funds and probably continued their 1950s role as a CIA proxy.

The author also provides an in depth discussion of the development of underground newspapers and the varied opinions it produced. It was clear that no uniform arguments as to how to proceed would be agreed to, but they all believed in the goal of ridding Poland of Soviet influence. English details how the underground was able to work around martial law, and the risks activists were subject to. Disagreement and risk are highlighted in the chapter entitled “The Regina Affair” as Marian Kaleka favored an enormous smuggling operation that would provide over $250 million worth of equipment, supplies and books. Chojecki opposed this as being too risky, and in the end he turned out to be correct as the first mission was a success, but Kaleka got “cocky” and sent an even larger mission which was broken up by the Polish SB.

English points to other aspects of the underground and key figures like Father Jerzy Popieluszko, a Catholic priest who preached against totalitarianism in his sermons. He would be killed by the Polish army and become a martyr, a grave error that reenergized the opposition to the government. The underground publication of Popieluszko’s sermons in November 1984 assisted by CIA assets was a defeat for the Polish government. The underground’s work was soon to be enhanced by technological changes emerging in the mid-1980s with the advent of computers, video, and video-related equipment, cassettes, and access to satellite communications funded by the CIA.

(Helena Luczywo)

As one reads English’s monograph one begins to question the role of the CIA for the greater part of the book. Finally, by the last third it’s role begins to emerge in a clearer fashion as the author recounts the events of 1989 which would bring Solidarity to power. The book’s title leads one to believe that the CIA was in charge of smuggling books and related material into the region, but the most important component was the resisting activists themselves. Joseph Finder is dead on in his July 13, 2025, New York Times Book Review as he writes; “Today, when “subversive” is the standard accolade for a campus poet, English’s book is a bracing reminder that, not so long ago, forbidden literature really could help tip the balance of history. He persuasively argues that the ferment in Poland, fueled in part by Minden’s cultural contraband, was a catalyst for the chain reaction that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the crumbling of other Eastern Bloc governments. “Soft power” wasn’t so soft.

That’s why the publication of “The CIA Book Club” feels perfectly, painfully timely. As President Trump takes a sledgehammer to U.S.A.I.D., Voice of America and Radio Free Europe — institutions of cultural diplomacy once backed by both parties — this chronicle reads like arequiem. George Minden types were convinced of the geopolitical force of ideals such as free expression and the rule of law because they actually believed in them. ‘Truth is contagious,’ Minden said. Our new stewards of statecraft, by contrast, seem to see the world in purely transactional terms, and to assume everyone else does too. English’s book is a reminder of what’s lost when a government no longer believes in the power of its own ideals.”

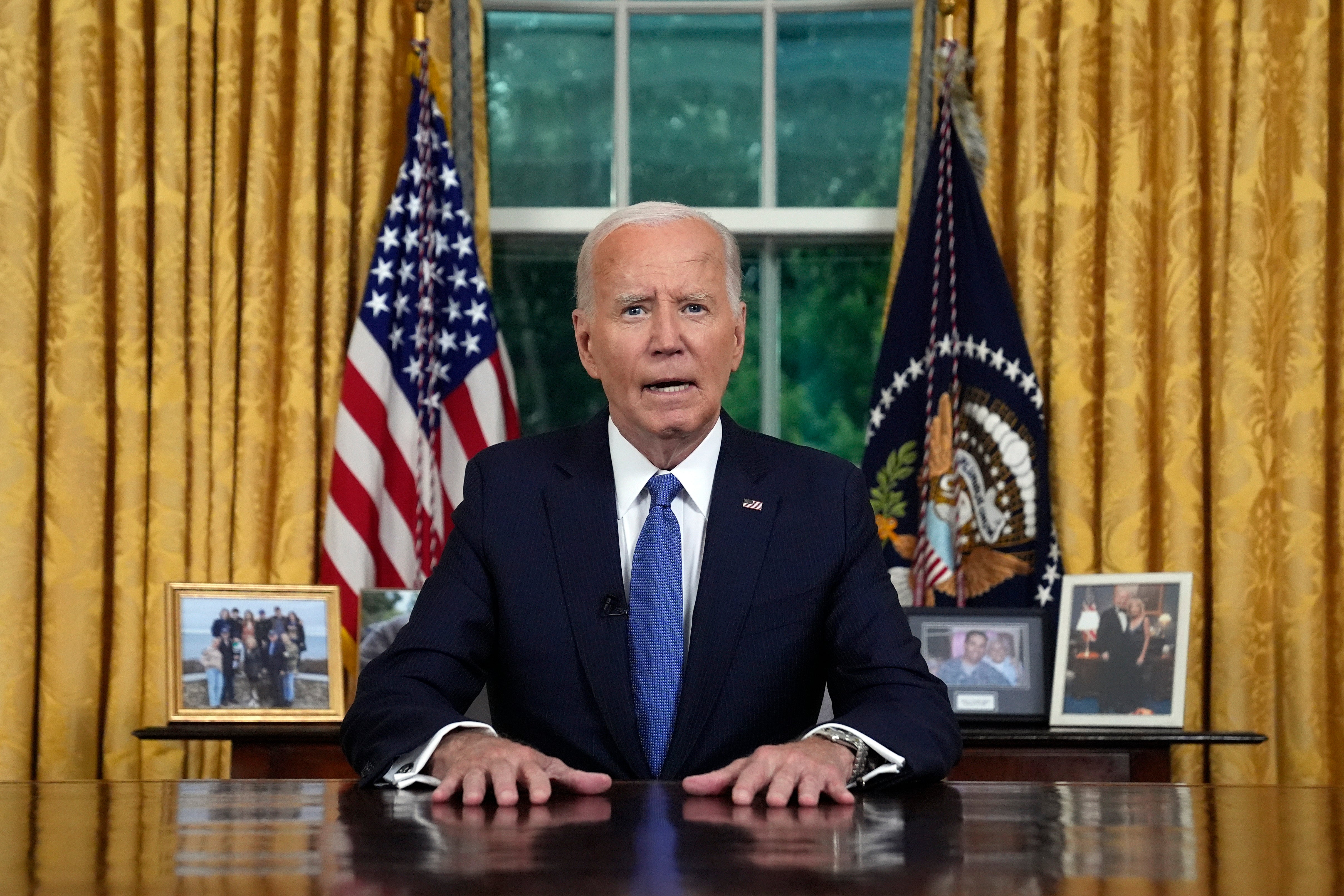

(Biden family photos sat behind President Joe Biden as he delivered his address to the nation)

(Biden family photos sat behind President Joe Biden as he delivered his address to the nation)

(President Joe Biden with family members nearby as he delivers remarks during an address from the Oval Office of the White House)

(President Joe Biden with family members nearby as he delivers remarks during an address from the Oval Office of the White House)

![Richard Nixon-[C]════ ⋆★⋆ ════

[C]“ 𝕋𝕙𝕖𝕪 𝕤𝕒𝕚𝕕 ‘𝕊𝕠𝕟, 𝕕𝕠𝕟’𝕥 𝕔𝕙𝕒𝕟𝕘𝕖’

[C]𝔸𝕟𝕕 𝕀 𝕜𝕖𝕖𝕡 𝕙𝕠𝕡𝕚𝕟𝕘 𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕪 𝕨𝕠𝕟’𝕥 𝕤𝕖𝕖 𝕙𝕠𝕨 𝕞𝕦𝕔𝕙 𝕀 𝕙𝕒𝕧𝕖 ”

[C](https://pm1.aminoapps.com/8046/e5369316bc74864ed586f9055db2050e01c23383r1-236-292v2_hq.jpg)

![Nazi camps in occupied Poland, 1939-1945 [LCID: pol72110] Nazi camps in occupied Poland, 1939-1945 [LCID: pol72110]](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/3482f20c-51c9-4b2e-ab6a-39a202c52f6c.gif)

![SS chief Heinrich Himmler (right) during a visit to the Auschwitz camp. [LCID: 50742] SS chief Heinrich Himmler (right) during a visit to the Auschwitz camp. [LCID: 50742]](https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/images/large/876bf59a-ccaf-4be4-a190-1ef087a18452.jpg)

(“I had known Prigozhin for a very long time, since the 1990s,” Vladimir Putin recalled)

(“I had known Prigozhin for a very long time, since the 1990s,” Vladimir Putin recalled)

(Yevgeny Prigozhin (left) pictured serving Vladimir Putin (centre) at a dinner in 2011)

(Yevgeny Prigozhin (left) pictured serving Vladimir Putin (centre) at a dinner in 2011) (Prigozhin became most vocal in a series of video statements from Bakhmut where he criticised the defence establishment)

(Prigozhin became most vocal in a series of video statements from Bakhmut where he criticised the defence establishment)