(A view of the cityscape in the aftermath of Israeli strikes, in Tehran, Iran, June 13, 2025).

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the arrival of the mullahs at the head of Iran’s attempt at theocracy relations with the United States have been fraught with hatred. Over the years wars, assassinations, terrorism, computer related attacks, spying, kidnappings, a nuclear deal and its revocation, and economic sanctions have been the norm. Today Iran finds itself at a crossroad. Its Supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is eighty-six years old and nearing the end of his reign, and as Karim Sadjadpour writes in his November/December 2025 issue of Foreign Affairs, “The Autumn of the Ayatollahs” the twelve day war last June laid bare the fragility of the system he built. Israel bombed Iranian urban centers and military installations, allowing the United States to drop fourteen bunker busting bombs on their nuclear sites. Tehran’s ideological bravado and its inability to protect its borders along with the defeat of its proxies, Hezbollah and Hamas has reduced its threat to the region.

Apart from the succession problem Iran faces a choice of how to prioritize its nuclear program, but with no negotiations, oversight, or concrete knowledge of Tehran’s stock of nuclear material another war with Israel seems inevitable. Despite Donald Trump’s insistence that the United States “obliterated” Iran’s nuclear enrichment program, officials and analysts are less sanguine. Iran may have been weakened, but it has not become irrelevant. As the rhetoric between Iran and the Trump administration ratchets up it is clear that the Tehran government suffered an ignominious defeat at the hands of Israel and the United States. The Iranian economy continues in a freefall, and the regime remains in power through coercion and threats. In this domestic and diplomatic climate, a novel that reflects the current forceful environment should attract a strong readership. THE PERSIAN by former CIA analyst and best-selling author David McCloskey, fits that need as the author takes readers deep into the shadow war between Iran and Israel and plays out a scenario that is quite plausible.

(Aerial view of Tehran, with the Alborz mountain range in the background)

McCloskey begins the novel describing the assassination of Abbas Shabani, an Iranian scientist who was an expert on drone-cladding, making drones invisible. The murder was carried out by a woman using a joystick at a Mossad site near Tel Aviv. The operation continues Israeli policy of killing anyone it believes is a threat to the Jewish state engaging in any component of Iran’s nuclear preparation – a policy that is accurate in fiction as well as the real world. McCloskey immediately shifts to an Iranian interrogation room where Kamran (Kam) Esfahani, a Persian Jewish dentist. Kam, the main character and narrator of this taut political thriller, is counting down the days until he has enough money to leave Sweden for sunny California. The interrogation allows Kam to rewrite and rework his confession over a three year period enabling the author to recount his novel through Kam’s acknowledgement of being part of a plot that killed Ismail Qaani, a member of the Qods Force, Unit 840. The group is run by Colonel Jaffer Ghorbani whose reason for being created is to kill Jews. Kam had been recruited by Arik Glitzman, head of the Mossad’s Caesarea Division, who offered to pay him a fortune to sow chaos in Iran. Trading the monotony of dentistry for the perils of espionage, he runs a sham dental practice in Tehran as a cover for smuggling weapons and conducting surveillance. McCloskey offers a wonderful description of Glitzman which is emblematic of his character development as the head of the elite team within the Caesarea Division of Mossad is described as “Napoleonic, short and paunchy with a thatch of black hair and a round face bright with a wide smile. There was fun in his eyes and if they had not belonged to a secret servant of the state…they might have belonged to a magician, or a kindergarten teacher.”

In addition to using Kam’s voice to relate a major part of the story, McCloskey organizes the novel by repeatedly shifting back and forth in time and location as he organizes his chapters. A key character who appears often is Roya Shabani who witnessed the assassination of her husband and seeks revenge against Israel. She will be given that opportunity as part of Ghorbani’s unit, initially carrying out low level tasks. Soon her immediate superior, Hossein Moghaddam, a Qods Operation Officer, who falls for her carries out an assassination of Meir Ben-Ami, Arik Glitzman’s deputy reflecting the real world that Israeli and Iranian intelligence regularly engage in.

(Stockholm, Sweden)

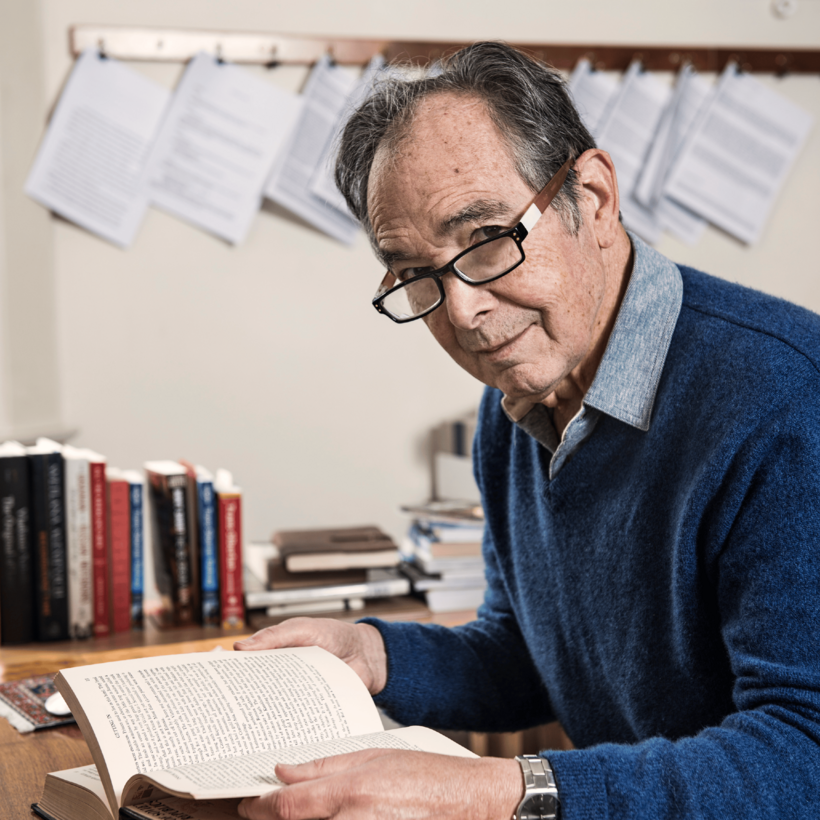

McCloskey’s CIA background and research allow him to portray assassinations, the use of technology for spy craft, recruitment of assets, and organizing operations in such a realistic manner heighten the reader’s immersion into the novel. In an NPR interview which took place on “All Things Considered” program on September 29, 2025, McCloskey admits that as a former CIA analyst who has been posted throughout the Middle East he is able to draw upon a great deal of inside knowledge in creating his characters and present them as authentically as possible. The authenticity of his characters and storyline is enhanced as his novel must pass through CIA censors and at times he is amazed as to what the “Publication Review Board” allowed to remain in the book. In a sense the book itself is prewritten as the actions of Iranian and Israeli intelligence officials and agents create the bones of an insane spy novel.

Aspects of McCloskey’s novel weigh heavily on the real world of espionage as the author delves into the fact that Israel was at a disadvantage in the world of espionage since it did not have diplomatic relations with the countries that surround her in the Arab world – it did not have embassies to hide intelligence officers who could carry out its operations. As a result, operational teams are cobbled together, surged to where they are needed, and disbanded when the operation is completed. Israel has to create different types of cover than the United States, United Kingdom and others because of this disadvantage and it amazes how successful they are when the playing field is not level.

(Caspien Sea)

McCloskey is very successful in creating multiple storylines as he goes back and forth between time periods and locations. A major shift occurs when the kidnapping of a target fails as somehow he is murdered. This causes Glitzman to change his plans on the fly resulting in Roya becoming a major focus of the novel. Her evolution from the spouse of a scientist to an espionage asset is fascinating as is that of Kam. The author does an exceptional job tracing Kam’s progression from an unsuccessful Iranian Jewish dentist raised in Sweden into a reluctant and fearful spy into someone who becomes devoted to his mission. The explanation that is offered makes sense as Kam develops his own feelings of revenge toward Iran and its agents who kicked his family out of the country, for decades has laid siege to the country of Israel and wants to eradicate its entire population. The problem is that his mission will result in his capture and the reader must wait until the last page to learn the entire truth bound up in his confession.

(Evin Prison’s main entrance)

The author’s goal in the book, which was already written before the war of last summer, was to go beneath that kind of overt conflict and get to the heart of the shadow war between Israel and Iran. After reading THE PERSIAN it is clear that he accomplishes his goal completely as his characters must survive in a world of intrigue, paranoia, and what appears to be a world of endless violent retribution.

(Tehran, Iran)

(The Zorg, a replica)

(The Zorg, a replica)