(GIs returning after WWII)

During his presidential campaigns Donald Trump has described American veterans as “suckers and losers.” He “strongly” wonders why veterans went off to fight when it was clear there was nothing in it for them. President Trump’s attitude toward men like John McCain and millions of others is both despicable and ungrateful. These men and women are heroes who defended our country and in most cases selflessly. Those who have survived war zones returned home with numerous ailments from the physical to the psychological. Today, the mental issues have been labeled post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) with veterans suffering from recurring nightmares and flashbacks, uncontrollable rages, social isolation, fears of places and events that evoked memories of the war, resulting in behaviors that they did not have before they shipped out. The label has been mostly applied to Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan war veterans, but symptoms were clearly evident for those who fought in and survived World War I and II.

In his latest book, award winning author David Nasaw, who has written such excellent works including; THE LAST MILLION which traces the plight of displaced persons after World War II, THE PATRIARCH a biography of Joseph P. Kennedy, THE CHIEF a biography of William Randolph Hearst, and ANDREW CARNEGIE, has just released a marvelous monograph entitled, THE WOUNDED GENERATION: COMING HOME AFTER WORLD WAR II. Nasaw’s focus in the book is not on the heroism of World War II veterans, but how they adapted to civilian life upon their return from the war, how their wartime experiences impacted familial and other personal relations, and how the country they returned to treated them. Nasaw’s most salient points revolve around the idea that these men and women were not the same people emotionally and physically as they were before the war, and the country which they returned to was quite different than the one they returned to. How they adjusted to their issues and their surroundings are the key to the narrative.

(American Sgt. George Black addressing the crowd of homesick GI’s as they staged a demonstration outside the US Embassy in the French capital in January, 1946. They protested the slowdown in their redeployment from Europe to the US)

As the author writes in his introduction, “if we are to understand the pain and hardship veterans brought home with them we must acknowledge their experiences in the war and of war, their wounds, injuries, and illnesses, their realization that they were expendable, that chance alone would determine whether they lived or dies or returned home body and soul intact,” therefore we must begin, not with their home coming but their actual experiences in the war.

Nasaw spends almost half the book discussing what soldiers experienced in combat, and at the same time how carefully the government informed the public of their plight with an eye on the issues they perceived would emerge once they were discharged. From the outset Nasaw focuses on the issue of “neuropsychiatric disorders” as the term PTSD was not known. It is clear that about 40% or about one million soldiers who were discharged or disabled during the first two years of the war fell into the category of “neuropsychiatric disorders.” The problem for military authorities was that the army and naval medical corps were totally unprepared to deal with psychiatric disorders. They were trained to deal with physical injuries, not mental, which were 33% of all injuries. With the shortage of men, many of these individuals were returned to the front suffering from symptoms of anxiety and depression. In treating these men, medical professionals were unsure if victims would ever recover.

As the narrative progresses the author makes many salient points, some obvious and others based on deeper analysis. The American public was fully aware of what their sons and daughters were experiencing despite military censorship. With an abundance of newspapers, magazines, books, and diaries the public was exposed to information on a delayed basis. However, radio reports made the experience more immediate. The government was in a bind, if it reported too many victories, particularly after the Battle of Midway authorities feared people would become complacent and the war might be close to an end. The government knowingly believed that in “total war” the fighting could drag on for years, particularly against Japan and wanted the public to be educated to that belief. By 1943, authorities in Washington wanted a more accurate representation of the fighting to be used as a tool against complacency in a war that had distinct racial elements to it.

John Dower’s book, WAR WITHOUT MERCY: RACE AND POWER IN THE PACIFIC WAR develops this racial thesis, especially in Asia as the reason for the horrible conditions that soldiers faced when dealing with the enemy. As Nasaw correctly points out, “American boys and men, once peaceful and non-violent souls, had to become merciless, pitiless killers in order to stay alive and defeat a merciless, pitiless enemy.” The American media would caricature the “Japanese as vicious, conniving, beastly hordes of ‘monkeys’ and ‘rats,’ unstoppable, demonic torturers and killers,” while Germans were said to be more law-abiding according to international convention ignoring the Holocaust.

(American troops in a snow-filled trench during the Battle of the Bulge)

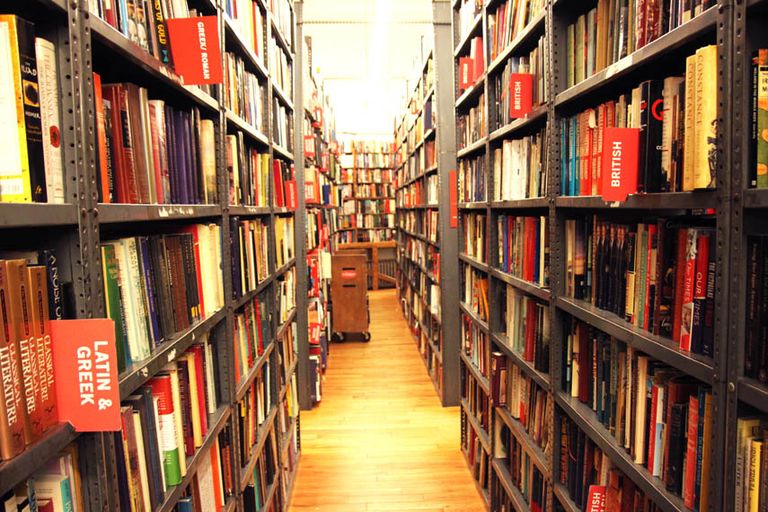

An interesting point that Nasaw describes deals with how soldiers spent their spare time. We have all heard the saying “hurry up and wait” pertaining to the military and even in combat that was true. Soldiers did not fight constantly, and outlets had to be provided for men and women. The creation of paperback books was boosted during the war as “pocketbooks” were created for soldiers to read as free reading material by the thousands was provided. The most important ancillary product provided was cigarettes which was seen as a military tool that would calm nerves before and after battle, suppress hunger, and keep soldiers alert when they should have been sleeping. During D-Day they helped to ward off sickness, reduce fear and shaking and sustain men. They were given to soldiers at every opportunity – 63 tons worth of tobacco were delivered to the army, and tobacco farmers were deemed “essential workers during the war. Soldiers were also seen as different if they did not smoke. Cigarettes were provided with C rations and were available everywhere as they were a major resource for soldiers to trade. Other activities that were employed to keep soldiers “sane” were alcohol and condoms. As with nicotine addiction, drinking habits acquired during the war would carry over into peacetime. Drinking served a similar purpose to smoking to calm soldiers and allow them to cope with the atrocities of combat. In addition, during the war over 50 million condoms were distributed by authorities who could not control the sexual drive of soldiers especially after they arrived in Italy in 1943. Women were readily available as prostitutes as locals resorted to sex as a means to earn money, cigarettes to trade on the black market, and just to survive.

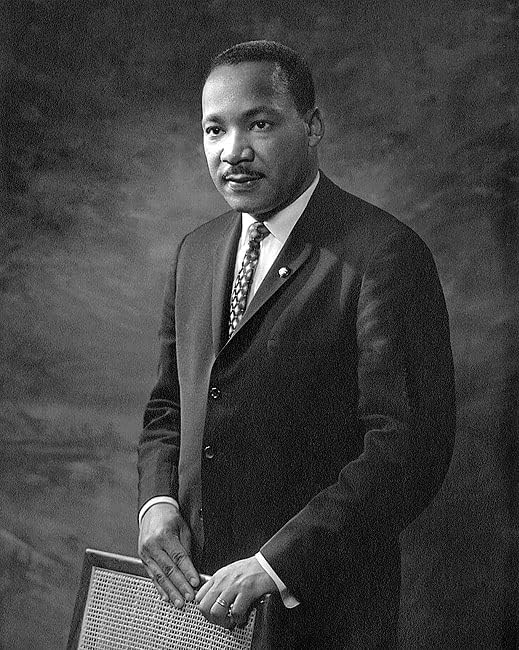

The racism that existed after the war, especially as Jim Crow was restored in the south, was a continuation of what went on in military theaters. At first negro soldiers were given menial jobs – cleaning, cooking, waiting tables, and general labor. Later as troop shortages continued experimentally, segregated units were created. These units did quite well, i.e., the Tuskegee Airman, and a few combat units. The fear on the part of southern senators was that if negroes got used to fair treatment and a better racial experience in the army it would carry over into civilian life and there would be certain expectations. They wanted Jim Crow in the army, so negroes did not get any ideas once they were discharged. The behavior of southern whites after the war reinforced Jim Crow as blocking voter registration, the return of brutal lynchings, and the refusal to hire negroes for other than menial jobs they had before the war, as opposed to employment which would allow them to use their military training and wartime experiences dominated race relations below the Mason-Dixon line.

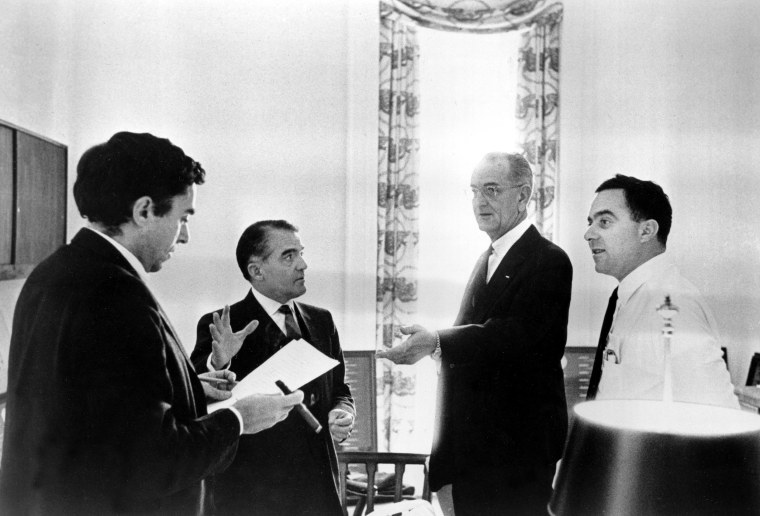

(FDR signs the GI Bill)

Nasaw does an excellent job discussing problems that developed once the allies proved victorious. The issue was demobilization. With the end of the war in Europe soldiers wanted to be discharged, not sent to the Pacific as the Japanese were seen as fighting to the death and after Okinawa, Saipan and the rest of the island hopping strategy was implemented they knew fighting could be brutal. European theater veterans were given 30 days leave and were then to be sent to the Pacific. The dropping of the atomic bomb ended the war for good and domestic politics called for a rapid demobilization, however the United States needed troops for occupation duty. Demobilization would be slow and about 1.5 million would be needed for occupation.

The author spends the remaining 60% of the book on how the war affected American society once fighting ended. Nasaw recounts the repatriation process and once again the racial issue arose as negroes were the last to be discharged. By stressing the racial component to the post war period, the author relies on excellent source material, diaries, interviews of families, and other primary materials.

Politicians in Washington did not want to deal with racial equality as the Democrats needed the support of southern senators to try and create a program which would reintegrate men and women back into civil society. Memories of the Bonus Army of 1931 during the depression and the use of the military to crush it were still fresh in people’s minds. The solution would evolve into the GI Bill whose rationale was not totally one of empathy but one to avoid unemployment, inflation , and retrofitting industry back to peacetime. By providing educational funding for tuition and books it would allow veterans to attend college and not enter the labor force which was undergoing a dramatic change as women began to lose their jobs as the men returned and wanted to reclaim their place in society. Whatever the motivation was for the GI Bill the government implemented a “veteran’s welfare state” throughout the 1940s.

What is clear is that the federal government spent a great deal on white returning veterans. Though Nasaw cannot settle on a figure as to how much the government spent; at times he states it is $17.3 billion, later it is $24 billion, and even later it is closer to $30 billion for the GI, bill the amount dwarfs what was spent on the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe after the war. Whatever the final figure was between 1945 and 1950 it was in the billions and went along way to implement the veterans’ welfare state of education, job training, medical care, and housing relief. Many in Congress called for expanding this approach to all civilians, but that was not in the cards for decades, and even then it did not match what was spend on white veterans.

Nasaw is clear that the major issue was that veterans brought the war home with them – many were psychologically wounded and many carried diseases within their bodies. Millions returned with undiagnosed untreated psychic wounds that would haunt them for years to come. Men had to live with what they saw and experienced no matter how emotionally devastating it was. For many, these experiences remained with them for the remainder of their lives. Men came home with the characteristics of PTSD, though it was called “combat fatigue” or something similar. When they returned they exhibited what psychiatrist, Robert Jay Lifton describes in his seminal work on survivors of the atomic bombings, DEATH AS IN LIFE as flashback, nightmares, violent tempers, survival guilt, psychic numbing, all indicative of PTSD. To make it even worse for women, children and the family unit, the military and society in general put the onus of helping their spouses recover on them. They had to grant veterans the leeway to recover which the military stated would eventually occur over time. Most veterans did not commit suicide and learned to live with nightmares and flashbacks they could not erase. In addition to PTSD, many individuals suffered traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) from concussive explosions during the war from which they had not recovered. All this made the recreation of the family unit as it was known before the war, impossible to recapture.

(Tuskegee Airmen)

Nasaw spends a great deal of time on the impact of the war on the family unit discussing the role of women who had lived independently during the war and now were faced with giving that up and allowing the husband to recapture his place as the breadwinner. Many could not and the divorce rate would almost double. The increase was also due to the fact that many men and women could not accept the infidelity of their spouses, women lonely at home, and men lonely overseas seeking comfort.

Nasaw seems to cover every aspect of how service in World War II impacted a myriad of issues following the fighting. His coverage is comprehensive, but he also provides a wonderful touch illustrating his monograph with Bill Mauldin cartoons which were rather provocative for the time period. Tom Brokaw has labeled those who were victorious in World War II as the “greatest generation.” After reading Nasaw’s excellent book I would change that label to the “long suffering generation.”

(Doctors returning to the United States in the Mediterranean or Atlantic circa October 1945, The National WWII Museum)

![Richard Nixon-[C]════ ⋆★⋆ ════

[C]“ 𝕋𝕙𝕖𝕪 𝕤𝕒𝕚𝕕 ‘𝕊𝕠𝕟, 𝕕𝕠𝕟’𝕥 𝕔𝕙𝕒𝕟𝕘𝕖’

[C]𝔸𝕟𝕕 𝕀 𝕜𝕖𝕖𝕡 𝕙𝕠𝕡𝕚𝕟𝕘 𝕥𝕙𝕖𝕪 𝕨𝕠𝕟’𝕥 𝕤𝕖𝕖 𝕙𝕠𝕨 𝕞𝕦𝕔𝕙 𝕀 𝕙𝕒𝕧𝕖 ”

[C](https://pm1.aminoapps.com/8046/e5369316bc74864ed586f9055db2050e01c23383r1-236-292v2_hq.jpg)

(John Lewis, third from left, walks with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as they begin the Selma to Montgomery march from Brown’s Chapel Church in Selma on March 21, 1965)

(John Lewis, third from left, walks with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as they begin the Selma to Montgomery march from Brown’s Chapel Church in Selma on March 21, 1965)

(Tear gas fills the air as state troopers, on orders from Gov. George Wallace, break up a march in Selma on March 7, 1965, on what is known as “Bloody Sunday”)

(Tear gas fills the air as state troopers, on orders from Gov. George Wallace, break up a march in Selma on March 7, 1965, on what is known as “Bloody Sunday”)