(President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser)

Today we witness a Middle East in crisis. In Iraq, ISIS remains a power though the current operation to reconquer Mosul could be the beginning of the end of the supposed caliphate. Syria is a humanitarian disaster as Russia and Iran continue to prop up Bashir Assad and keep him in power. As the Syrian Civil War continues, war in Yemen involving Saudi Arabia, an American strategic ally evolves further. The seeming winner in this juxtaposition of events is Iran which has taken advantage of the American invasion of Iraq, and how the region has since unraveled. Once ISIS is removed from Iraq it will be interesting to see how Kurdish, Shiite, and Sunni factions “might” try to reconstitute their country. It seems an afterthought to this untenable situation that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict featuring Hamas, an intransigent Israeli government, and Hezbollah in the north has somewhat faded into the background. As we contemplate the morass that is the current Middle East it is interesting to return to the by gone days of the region in the 1950s when Arab nationalism/Pan Arabism was in vogue as opposed to the religious ideological road blocks of today. In IKE”S GAMBLE: AMERICA’S RISE TO DOMINANCE IN THE MIDDLE EAST, senior director of the National Security Council under George W. Bush, Michael Doran has revisited an American strategy to deal with the myriad of problems then in the region, that laid the foundation for America’s role in the area that we continue to grapple with today.

(President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles)

According to Doran when President Dwight D. Eisenhower assumed the presidency, he and his Secretary of State John Foster Dulles decided to offer the president as “an honest broker” in the Middle East to try and settle intra-Arab, and the Arab-Israeli conflict. The term “honest broker” is an interesting one unless you think of it as a realpolitik based on power politics designed to drive the British from the region and replace it with American influence and control. In 1952, Egypt had undergone a revolution and replaced King Farouk’s government with one based on a “Free Officers Movement” dominated by Colonel Gamal Abdul Nasser, an Egyptian nationalist and believer in uniting the Arab world under Egyptian leadership. The British position in the region was tenuous, despite the presence of 100,000 troops at their Suez Canal base. Their Hashemite allies in Jordan and Iraq feared what was termed as “Nasserism,” the Arab-Israeli conflict was punctuated with “Fedayeen” attacks against Israel, and retaliation by the Jewish state all served to make the region a powder keg. For incoming President Eisenhower he was concerned with dealing with a region that was ripe for communist expansion in the guise of anti-colonialism. Dulles learned firsthand about these tensions when he visited the region in May, 1953 and upon his return he and the president decided on a strategy to remove the British from their Suez base by brokering a treaty that was accomplished by October, 1954, and trying to settle issues between Egypt and Israel that were getting out of hand. For the British it was a series of frustrations with the Eisenhower administration that dominated. Prime Minister Winston Churchill refused to pass leadership of the Conservative party to Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden despite a stroke that left him partially paralyzed on his left side as he would not give in to Egyptian demands and sacrifice the last remaining bulwark of the British Empire. For the United States their ties to British and French imperialism and the closeness of American-Israeli relations were seen as preventing any progress in the Middle East toward peace. This resulted in a policy which set as its goal supporting Nasser in the belief he would cooperate with the United States once a treaty with Israel was arrived at, the end result of which for the Eisenhower administration would be his leadership and gaining the support of the Arab states for a Middle East Defense Organization designed to block Soviet penetration of the region. The United States would woo Nasser with economic aid and promises of military largesse for over four years, a policy that would fail as the Egyptian president was able to dupe his American counterparts.

(British Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden)

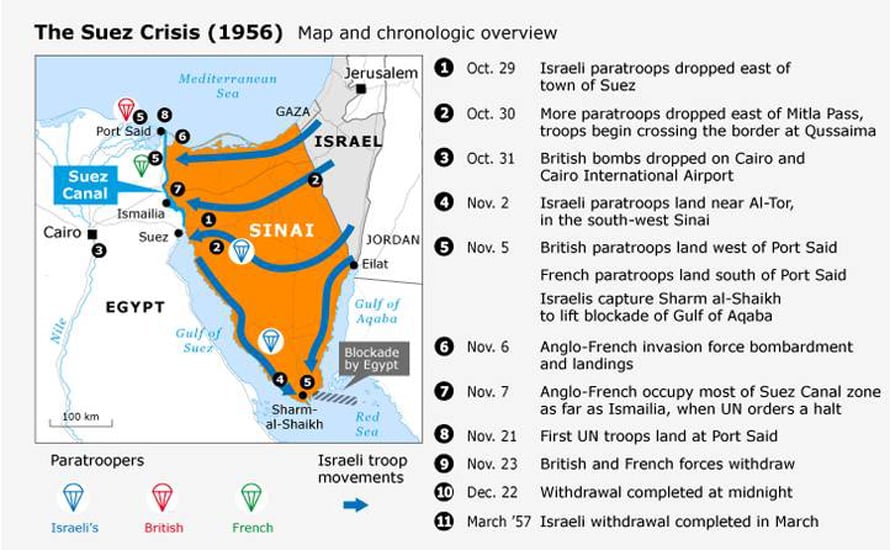

With the above as background, Doran begins to unravel events that resulted in the 1956 Suez War that he describes as Eisenhower’s gamble, a gamble which ended in failure. Doran takes us through the intricacies of Anglo-Egyptian negotiations over the Suez Canal base and the American role in pressuring London to give in to most of Nasser’s demands. He follows that up with a rather long discussion of the “Northern Tier,” an American policy of developing an alternative to a Middle East Defense Organization. The “tier” involved Pakistan and Turkey and theoretically other nations would be added. Doran argues that Nasser’s opposition to the pact and his hatred of Iraqi leader Nuri al-Said, his goal of receiving Soviet arms, and deceiving the United States were all tied together reflecting how Nasser manipulated Washington. Relying on one secondary source to bind all of this together Doran believes that he has gone where no other historian has gone. This is part of his rather condescending approach to historians who have previously studied this topic. On more than one occasion Doran starts out by stating, “most historians have failed to understand how significant….,” or “failed to realize,” in this case the importance of the Turco-Iraqi Pact, or in presenting the role of Eisenhower and Dulles in the Heads of Agreement negotiations dealing with the Suez Canal base, and the role of Jordan in Nasser’s plan to seize the leadership in the Arab world. I would point out that instead of repeated self-serving comments, the author should reflect some objectivity for those who have written previously on the background to the Suez crisis.

(Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion)

Doran also has a habit of twisting facts to suit his arguments. A case in point is a memo prepared by Dulles in 1958 looking back on issues that led to Suez. In the memo that Doran uses to support his narrative the Secretary of State argues there was little the United States could do to move Israel from its entrenched positions because of the influence of Jews domestically and internationally. If this was so, how come Eisenhower pressured Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion with threats in March, 1957 to gain Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai? Further he claims that the Soviet Union, “while consistently hinting to the Arab states that it will agree to dismember Israel, has never actually come out with a statement of support.” If that is correct what do we make of Soviet threats concerning the use of nuclear weapons after Israel, France, and Britain implemented the Sevres conspiracy and attacked Egypt at the end of October, 1956?

I do agree with Doran that Washington’s “blind pursuit of an illusionary Arab-Israeli peace” strengthened Nasser’s position in the Arab world, at the same time he was trying to undermine the western position in the region. Nasser deceived the State Department, raising the hopes for peace through the secret Alpha Plan. The Egyptian leaders stalling tactics and disingenuousness would continue until the Eisenhower administration would call Nasser’s bluff following the Anderson peace mission in early 1956, a mission that would lead to the Omega plan designed to pressure Nasser to be more accommodating. Doran points out that the new plan was designed to deal with Nasser and achieve behavioral change, not regime change. I would point out that the document also alluded to strong action particularly if a soft covert approach did not work as Dulles’ March 28, 1956 memo stated that “planning should be undertaken at once with a view to possibly more drastic action in the event that the above courses of action do not have the desired effect.”* For Eisenhower, whose frustration with Nasser finally took effect there were suggestions that a strong move against the Egyptian president would have to wait until after the American presidential election in November.

Doran continues his narrative by taking the reader through the immediate causes of the Suez War, the machinations that occurred after the Israeli invasion, and the final withdrawal of Israeli, French, and British troops from Sinai. The author then goes on to discuss the anti-colonial purity of the Eisenhower administration which was short lived with the announcement of the Eisenhower Doctrine in January, 1957, designed to protect Arab states from communist encroachment. The reality was total failure of American policy with the overthrow of the Iraqi government and the dispatch of American marines to Lebanon. In addition, the goal of turning the Saudi monarchy into a substitute for Nasser as an Arab leader that would bring about a coalescing of Arab states in support of U.S. policy in the region never transpired. In the end I would agree with Doran that Ike’s gamble did more harm than good and by 1958 resulted in the president questioning his policies that led to the 1956 war and beyond. These musings by Eisenhower and the counterfactual scenarios presented by the author are interesting, but it does not change the fact that the team of Eisenhower and Dulles did create a popular Arab leader who was able to create strong Pan Arabist sentiment in the Middle East and left the United States with two weak allies in Jordan and Lebanon. Further, they created a “doctrine” for the Middle East that was viewed in the Arab world as the same type of colonialism that had been previously practiced by England and France. Doran completes his narrative by admonishing American policy makers that we should be careful not to make the same errors today that we made in the height of the Cold War.

*Steven Z. Freiberger. DAWN OVER SUEZ: THE RISE OF AMERICAN POWER IN THE MIDDLE EAST 1953-1957 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1992), p. 149.

(President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser)