For the last few years, the historiography of allied bombing during World War II has undergone much greater scrutiny. The death and destruction of civilians and their property has been labeled as unethical and immoral as cities such as Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo and of course German bombing of allied cities experienced a level of violence that was unprecedented when compared to the pre-World War II era. The role of technology in the process cannot be downplayed without which the carnage of war would not have reached the levels it did. Malcom Gladwell, the spirited writer for The New Yorker normally explores the realm of social psychology, but in his latest work, THE BOMBER MAFIA: A DREAM, A TEMPTATION, AND THE LONGEST NIGHT OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR he turns his focus on to a group known as the “Bomber Mafia” that argued for a new type of bombing during wartime. The group was made up of generals who went against the standard view of warfare put forth by the U.S. Army and Navy and broke away from the ideology of the Army Air Corps and set up the Army Air Corps Tactical School at Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama. Gladwell’s focus is on four generals particularly the much maligned Air Force General Curtis LeMay who led and designed American air power that culminated in the firebombing destruction of German and Japanese cities.

Gladwell creates the juxtaposition of Air Force General Haywood Hansell who tried to win the war in the Pacific Theater through precision bombing of Japan. According to Gladwell this strategy was unsuccessful and gave way to LeMay’s approach whose goal was to win the war against Japan as soon as possible by saturating Tokyo with napalm bombs which would result in the death of over 100,000 people in just a few hours and went on to firebomb other Japanese cities killing thousands of civilians that held no strategic value. Gladwell concludes that LeMay’s approach followed by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the war and set the United States and Japan on the road to peace and prosperity much quicker than had Washington pursued a more conventional approach to warfare into 1946 that would have killed millions of Japanese civilians and who knows how many American soldiers.

Gladwell’s work can be considered anti-revisionist or the new revisionism as without mentioning the likes of Gar Alperovitz’s ATOMIC DIPLOMACY, he purports that the United States pursued their strategy to end the war quickly and was not sending a message that would spark the Cold War. Gladwell’s fascination with “bombing” during World War II stems from his childhood in London where his father recounted the horrors brought on by the German Luftwaffe over the English capitol and other cities. As Gladwell mines his topic, he includes portraits of the most important characters involved. Men like General Haywood Hansell; General Lauris Norstad who fired Hansell; General Curtis Le May; General Ira Eaker, the head of the 8th Air Force bombers stationed in England; Frederick Lindemann, a friend of Churchill who helped alter the British Prime Minister’s view of strategic bombing; RAF Marshall Arthur Harris, who doggedly opposed the new American approach to bombing; Louis Fieser, a Harvard chemistry professor, who is credited with developing a Dupont chemical along with E.B. Hershberg and created an incendiary gel known as napalm; and perhaps the most important person in the process, Carl L. Norden, the inventor of the “bombsight” that allowed true precision bombing are all explored among a number of others. Gladwell is correct when he argues that the firing of Hansell in Guam on January 6, 1945 set the United States on a strategic road that still reverberates today.

Gladwell states his goal in writing the book was to present what led up to the firing of Hansell, what changes were made, and how the shift in US strategy had implications for the war itself and the future conduct of warfare. For Gladwell, “THE BOMBER MAFIA is a case study in how dreams go awry.” A strategy designed to save lives during wartime in the end did not result in the goals set out by this group of Air Force Generals. Instead, a Dutch genius and his home made computer who developed the 55 pound bombsight; a “band of brothers” in Alabama; a British psychopath; and pyromaniacal chemists in basement labs at Harvard were responsible for the creation of a weapon that still affects us on a daily basis.

Gladwell begins by explaining how difficult it is to successfully hit a target on the ground from thousands of feet in the air. The key to solving this conundrum was the work of Carl Norden who began working on his bombsight in the 1920s. After its development it would take six months to be trained on the Norden bombsight and if it were a success these powerful men thought we would no longer need to leave young men dead on the battlefield or lay waste to entire cities. War would be made “precise and quick and almost bloodless. Almost.”

The Bomber Mafia’s mantra was “high altitude. Daylight. Precision bombing.” These men had a radical mind set much different than the army and navy and passionately believed that they were pursuing a revolutionary goal. Gladwell explores this group with deft, but not overwhelming detail and to lighten the reader a bit he provides priceless descriptions of a number of characters. The nicknames he provides labeling Arthur Harris as “Butcher Harris,” Carl Norden as “old man dynamite,” a devoted Christian who believed he was saving lives, Haywood Hansell was called possum, and Curtis LeMay was described as “brutal” by Robert McNamara as all provide insights to the type of people that Gladwell describes.

One of the major strengths of Gladwell’s narrative is how he integrates historical experts, World War II aviators, and comments by other participants providing the reader with greater insight than most into the thinking of the major characters. These characters would be successful in their mission to end the war early but by 1943 they had hit a wall as disagreements with the British, missions that failed to live up to expectations, and inter-service rivalries played a role. What is interesting is that LeMay was not part of the “Bomber Mafia” circle. He was drawn to practical challenges and doctrine left him cold.

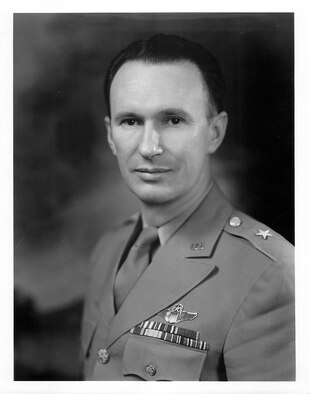

(Major General Haywood Hansell)

Gladwell’s digressions are entertaining but also educational as he pontificates on weather technology, cloud formations and wind over Japan, along with descriptions of certain chemicals and their strengths and weaknesses. One of those chemicals would lead to the development of napalm a discovery that probably did more to end the war than Norden’s bombsight. Napalm was chosen by LeMay as the key component in devastating Japan and ending the war quickly. Once he took over the 21st Bomber Command from Hansell in January 1945 he would soon realize the difficulties that Hansell faced and the obstacles in directing precision bombing against Japanese industrial capacity on the mainland. LeMay changed American bombing strategy by adopting a low flying approach that was the antithesis of the Bomber Mafia’s methodology. Gladwell’s chapter “It’s All Ashes” is an incisive look at how LeMay’s personality and modus operandi would lead to the events of the night of March 9, 1945. Gladwell describes LeMay as suppressing his own nerves and fears as he focuses on the mission that ultimately dropped 1,665 tons of napalm on Tokyo over a three hour period burning everything for sixteen square miles and the death of over 100,000 people. LeMay’s planes would continue to wreak havoc, death, and devastation on 67 Japanese cities killing at least 500,000 or perhaps 1,000,000 people before the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After the atomic explosions LeMay continued to bomb Japanese cities as he believed the nuclear attacks were superfluous as the hard work had already been done. One can debate the necessity for this type of devastation, but Gladwell is correct in arguing that it was so effective that it must be given credit for shortening the war.

In summation it is clear Gladwell has written an informative and important new slant on World War II bombing and I agree with historian, Diana Preston’s conclusions in her April 23, 2021 review in the Washington Post, “Gladwell does however confront us with difficult questions: “Ask yourself — What would I have done?” he suggests at one point. In so doing he has produced a thought-provoking, accessible account of how people respond to difficult choices in difficult times. Albert Einstein once warned that “our technology has exceeded our humanity.” Gladwell suggests that, given their concern not to cross a moral line, the Bomber Mafia would have approved of modern technical innovations like the B-2 stealth bomber, capable of precision strikes on military targets while minimizing civilian casualties. Yet ingenuity and conscience always sit uneasily in warfare, and Einstein’s warning should not be forgotten.” But in the end Gladwell is correct as high altitude precision bombing soon replaced firebombing – “Curtis LeMay won the battle. Haywood Hansell won the war.”