The Vietnam War which ended close to forty-four years ago seems to recede further and further into our collective memory as time moves on. Over time this movement has been slowed by the appearance of numerous novels that depict the horrors of the war and its tortuous effect on those who fought in southeast Asia, and the civilians who suffered and died. The best of these novels, many of which were written by former soldiers include; Philip Caputo’s A RUMOR OF WAR, Stephen Wright’s MEDITATIONS IN GREEN, Tim O’Brien’s THE THINGS THEY CARRIED, and more recently, Karl Marlantes’ MATTERHORN. All of these works depict the insanity of war and the outright lies associated with America’s experience in Vietnam. In considering this genre, Kent Anderson’s SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL should be added to the list as it witnesses the cruelty, duplicity, and disgust that soldiers experienced when they were supposedly fighting a war in defense of American national security.

From the outset, Anderson’s novel depicts the hypocrisy of the war as American troops get ready for a surprise presidential visit. Further, he describes how American troops cross over into Laos to conduct a bomb assessment, a euphemism for a body count after illegal B-52 strikes in a foreign country. Anderson tells his story through the eyes of SGT Hanson, who enlisted in the army after three years of college, volunteered for Special Forces, completed a tour of duty in Vietnam, and then reenlisted for another tour when he could not readapt to civilian life. Hanson is a fascinating character as he becomes a hardened combat veteran he continues to carry a book of Yeats’ poetry with him as he engages the enemy.

(173rd Airborne)

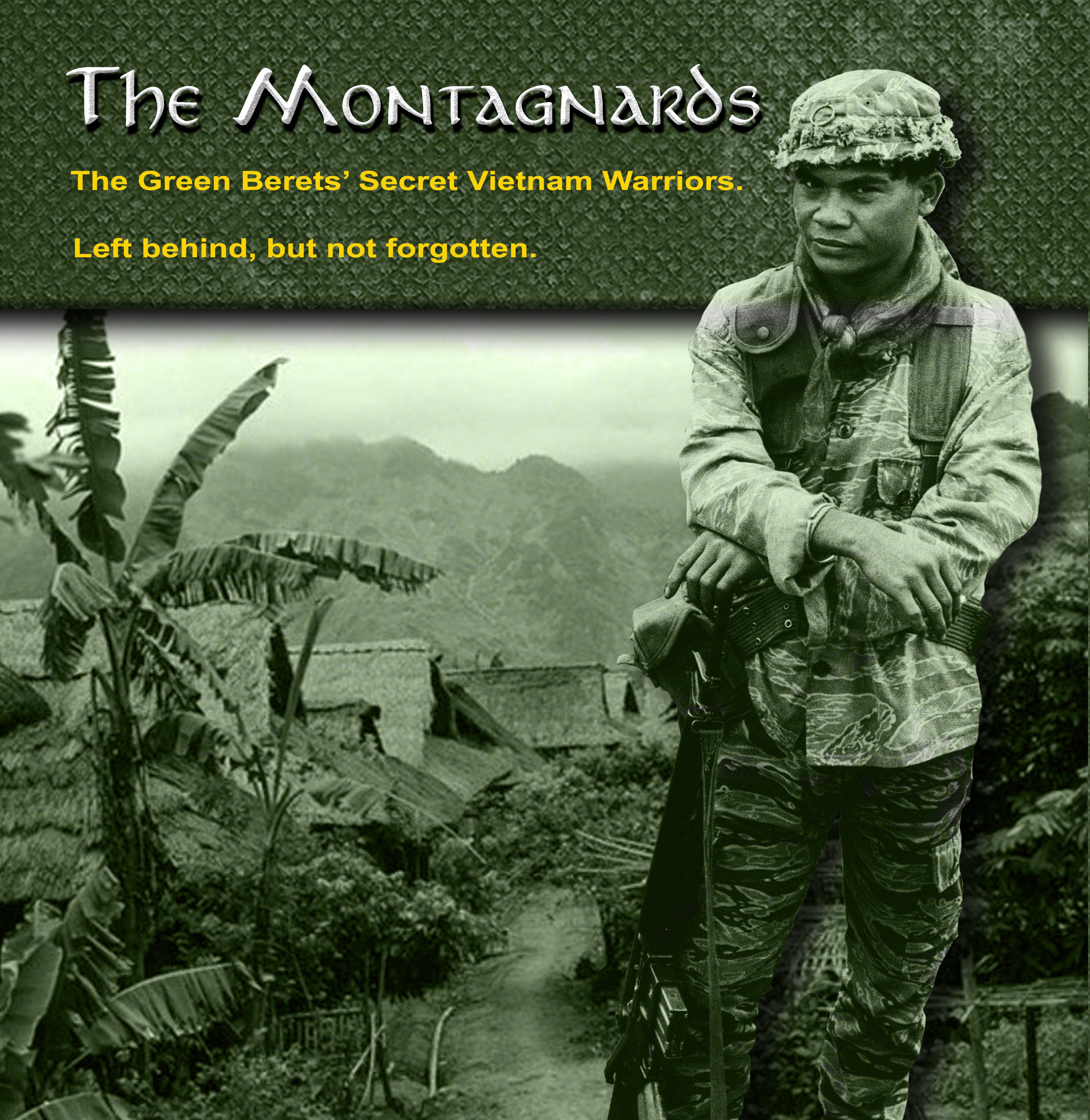

The first quarter of the book introduces Hanson and his buddies and how they viewed their experience in Vietnam. Anderson’s characters include, Hanson, the main protagonist; Quinn his buddy on both tours, a mean and violent individual who excels at gathering souvenirs from enemy bodies; Kitteridge, a senior supply NCO who built a profitable empire reallocating equipment away from their assigned destinations; Silver, a short and wiry individual who spoke fast and walked with a slight limp; Mr. Minh, a Montagnard tribal leader who studies of katha allowed him to make predictions that usually proved to be true; Lieutenant Andre, Hanson’s first field commander who enlisted while in law school; Warrant Officer Gierson, a pompous man from Texas who loved to hear his own voice, and lastly, the crazy SGT-MAJOR, who Hanson looked up to as a father figure and taught him how to stay alive.

One of the most important aspects of the book are Anderson’s observations about the war that comes across through the dialogue between characters. One of the most haunting is how in America one witnesses children crying all the time, while in Vietnam, children never shed tears no matter how much horror they experience. Another is how the Vietnamese try to Americanize themselves in order to please GIs and make a profit-by altering the looks of women making them appear more westernized, the type of music they choose, and the language they expressed. When GIs returned to the United States they were spat upon, cursed, and in general treated quite poorly, particularly Hanson who could not deal with this type of reception and decided he felt more comfortable and accepted in Vietnam. What is very unsettling is the way Americans viewed their Vietnamese counterparts. For men like Quinn, they were lazy and to be despised. It reached the point that Americans only relied on themselves as they did not trust their Vietnamese allies to fight. Further, they were aware of the hatred between the Montagnard tribesmen and the Vietnamese but saw the tribesmen as individuals who could be relied upon and they became true allies that could be trusted.

An interesting aspect is the realization by American troops, Hanson, Quinn, and Silver in particular how it soon became clear that inflicting and overcoming pain, and the possession and disbursement of power were the keys to survival. As Hanson experienced the war the real world made less and less sense to him, and the world of combat elevated his comfort level as he developed what he saw as a skill – the ability to kill, which reflected power.

The issue of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is front and center in the novel. Even before Hanson arrives in the US after his first tour there is evidence of PTSD as he hides a Russian pistol he had taken off an NVA body. His rationalization is that for “eighteen months he never went anywhere without a weapon, he was not going to start now.” Hanson comes to realize that he is always angry and makes one wonder if it is the war that “pisses him off” or is it something deeper. Once Hanson’s emotional state is laid bare Anderson returns to why Hanson enlisted in the first place and what it was it like to join the military. The author’s discussion of induction and basic training is standard US Army harassment, humiliation, and demeaning of people for fresh troops to lose their individual identity and become more of a unit. Anyone who has experienced this preparation for combat will not be surprised or possibly disturbed by what they read. It still seems that all drill instructors must have gone to the same school of language and psychological training that still rings in my ears almost fifty years later. The racism, hatred and lack of empathy are standard practice and drove one GI to try and commit suicide, but for Hanson it created a mindset on how he would survive. He decided that he did not want to go to war with bullies, sadists, and cowards. As a result, he underwent training for the Green Berets and extended his tour.

Anderson’s novel presents a remarkable destruction of a person’s sense of self. Hanson seemed to be a somewhat adjusted individual when he left college and joined the army. As his military training and experiences evolved his personality began to deteriorate as he succumbs to the evil he witnessed, and his more empathetic traits receded into the background. As Lt. Andre had stated the war held “no mistrials, no court of appeals, things are final.” For Hanson his return to Vietnam for his second tour after his negative experience back home became his security blanket and it was reflected by his actions and comments.

The final episode Hanson experiences in Vietnam is right out of the films, Platoon and Apocalypse Now, reflecting the outright absurdity of war, and the callous way it was approached by the United States. If that was Anderson’s message to his audience, he effectively transmits it. The novel is a gripping look at Vietnam, its effect on those who fought it, and is a remarkable addition to those books that have come before it that have similar themes.