There are numerous biographies of Sigmund Freud, the best ones I have read include Peter Gay’s FREUD: A LIFE FOR OUR TIMES, Joel Whitebrook’s FREUD: AN INTELLECTUAL BIOGRAPHY, and an earlier work, Ronald W. Clark’s FREUD: THE MAN AND THE CAUSE. The latest monograph SAVING FREUD: THE RESCUERS WHO BROUGHT HIM TO FREEDOM by Andrew Nagorski is not a complete biography but one that focuses on how Freud and fifteen of his followers managed to escape Austria in 1938 as Hitler and his Nazis achieved their Anschluss with Austria triggering a wave of anti-Semitic violence. While Nagorski provides biographical details of Freud’s life, his main thrust is the years leading up to World War II. Nagorski tells an engrossing tale of how there was little margin for error for Freud as he escaped Nazi persecution.

Nagorski a former Newsweek correspondent has written a number of excellent works dealing with 1930s and World II, including HITLERLAND: AMERICAN EYEWITNESSES TO THE NAZI RISE TO POWER, THE NAZI HUNTERS, 1941: THE YEAR GERMANY LOST THE WAR, and THE GREATEST BATTLE: STALIN, HITLER AND THE DESPARATE STRUGGLE FOR MOSCOW THAT CHANGED THE COURSE OF WORLD WAR II. In all instances Nagorski’s works reflect superb command of his material based on extensive research of secondary and primary materials, including significant interviews with his subject’s contemporaries and descendants. His latest effort is no exception.

When the Nazis took over Austria Freud was eighty two years old having spent most of his life in Vienna. The founder of psychoanalysis found himself in the middle of an unfolding nightmare. Many have asked why Freud and his family did not leave Vienna earlier as the Nazi handwriting was on the wall and early on it was relatively easy to do so. After his apartment and publishing house were attacked, his daughter Anna’s arrest and interrogation by the Gestapo, Freud still hoped to ride out the storm expecting “that a normal rhythm would be restored, and honest men permitted to go on their ways without fear.” Struggling with cancer, Freud was in denial knowing that he had little time left and did not want to go through the upheaval of relocating. It would take an ad hoc rescue squad to arrange his escape from Vienna that included sixteen people, made up of family members and his doctor and family.

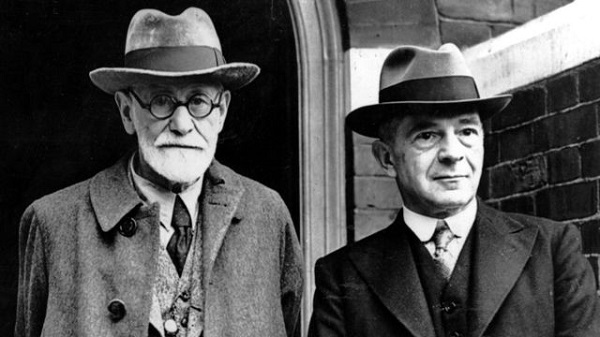

If it were not a true story Freud’s escape to live out his last fifteen months in London would make a superb spy novel. After presenting useful biographical chapters where Nagorski focused on the development of Freudian theories, he concentrated on his relationships with contemporaries like Carl Jung and Ernest Jones. This was important to Freud because as he developed a psychiatric following he worried they were dominated by Jews. Freud was very concerned that his life’s work was becoming a target for anti-Semites who screamed it was a “Jew science.” Freud would cultivate promising non-Jewish psychoanalysts as Nagorski points out his relationships with Carl Jung and Ernest Jones were partly fostered because they were Christians. Of the two, Jones would become a lifelong friend and colleague and would play a prominent role in Freud’s escape from Austria in 1938.

Nagorski delves deeply into the Freud-Jung relationship which at one point saw Freud anoint his friend the heir to his leadership in the psychoanalytic community. As time progressed Freud’s opinion of Jung declined believing he had become a man of “mystical tendencies” that prevented a clear scientific approach to his work. Further he believed Jung had developed a “confused mind,” and may have had anti-Semitic tendencies. By 1914 their break was complete.

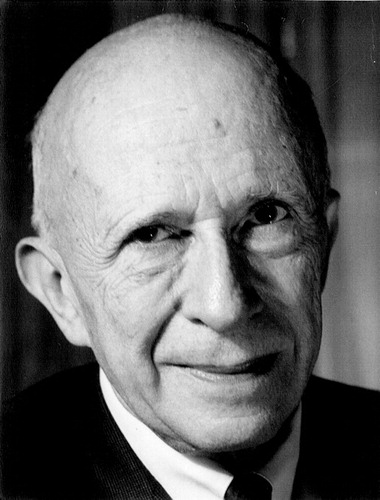

Nagorski provides an important window into what Vienna experienced before, during and after World War I in addition to the 1920s leading to the eventual Anschluss with Germany in 1938. He delves into the intellectual and cultural life of the city and the important personalities involved. An additional key to Nagorski’s narrative is how the lives and beliefs of Freud’s “rescue squad” evolved. The most important seems to be Ernest Jones, the Englishman who became Freud’s closest friend, biographer, and a psychoanalyst in his own right. Others include William C. Bullit, an American journalist and ambassador to Russia and France who developed an important relationship with Freud. Both men despised President Woodrow Wilson seeing him as an egotistical personality whose actions at the Versailles Conference they opposed. In addition, they co-wrote a psychohistory of the former president which was not published until 1967 long after Freud’s death. Marie Bonaparte, a former patient of Freud’s plays a significant role as Napoleon’s great grandniece who had many important contacts and funds to help finance Freud’s escape and like many of his patients went on to be a psychotherapist in her own right. Dr. Max Schur, Freud’s doctor during the last decade of his life and a man who kept him on an even keel. Anton Sauerwald, a Nazi trustee in charge of dealing with the Freud family after the Anschluss was a rather mysterious character. Lastly, and most importantly Freud’s daughter Anna, who became his lifelong caretaker and developed her own career in psychiatry focusing on the mental health of children. All pursued interesting lives and the mini biographies presented enhance Nagorski’s narrative.

Most people are unaware of Freud’s disdain for the United States. He visited America in 1909 and was taken aback by American materialism and lack of intellect. As noted previously he opposed the policies of Woodrow Wilson, and he would not consider the United States as a place to emigrate after the Anschluss. Nagorski points out that Freud was a German nationalist whose predictions pertaining to World War I were off base. He believed it would be devastating to both sides, but for him it became more bloody and destructive than anyone could have imagined. Freud came to realize the consequences of the war and was rather prophetic in his comments based on events in the 1930s.

Rachel Newcomb in her September 2, 2022 , Washington Post review of Nagorski’s work addresses why it took Freud so long to agree to leave Austria arguing, “Freud continued to believe that Austria would maintain its independence from Germany, right up until March 1938, when Hitler made his final push into Vienna, cheered on by a mob of rabid supporters. Gangs ransacked Jewish businesses, including the psychoanalytic publishing house managed by Freud’s son Martin, while brownshirts paid a visit to the Freud household and had to be bribed the equivalent of $840 to leave them alone. Yet Freud continued to refuse his colleagues’ entreaties to leave. Suffering from cancer of the jaw, acquired from a habit of smoking 20 cigars a day, he was already in his 80s and knew he did not have much time left. When asked later why he had delayed his departure so long, his daughter Anna Freud blamed his illness as well as his inability to “imagine any ‘new life’ elsewhere. What he knew was that there were only a few grains of sand left in the clock — and that would be that.” But once Anna was arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo, Freud realized that to ensure her future, he would have to leave Austria.”

Newcomb is correct in her analysis and nicely sums up the overall impact of the book writing, “readers looking for an in-depth exploration of the tenets of psychoanalysis will not find that here, but SAVING FREUD contains just enough about the central themes of Freud’s professional life to give a sense of his impact on the discipline he is largely credited with inventing. Unlike other, more critical biographies, the Freud that emerges from these pages is warm, avuncular and excessively fond of Anna, who he knew would carry on his legacy. The narrative pace and Nagorski’s fluid writing give this book the character of an adventure story. It is an engrossing but sobering read that reminds us how many others without the resources of the Freud family had no similar options to make an exodus.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-515296504-81e4865310b14a229157e7d9ab151634.jpg)