If you are looking for a reasonably compact review of Russian history encompassing the last three decades of the twentieth century, Princeton University historian and fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, Stephen Kotkin’s book ARMAGEDDON AVERTED, THE SOVIET COLLAPSE 1970-2000 should be considered. Published in 2008 it foresaw some of the problems we are experiencing today with Russia and looking back fourteen years later Kotkin would not be shocked by Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Kotkin has written two volumes of his biographical trilogy of Joseph Stalin; STALIN: PARADOXES OF POWER, 1878-1928 and STALIN: WAITING FOR HITLER, 1929-1941, one of which was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Kotkin is an exceptional historian blessed with a pleasing writing style and the ability to synthesize vast amounts of historical information and documentation that the general reader along with professional colleagues can admire and enjoy. With the war raging in Ukraine, Kotkin provides insights into Putin’s thought process and the impact of the 1970-2000 period on the Russian autocrat that explains a great deal of his actions.

A key theme in Kotkin’s monograph is his stated purpose in authoring the book; try and explain why the Soviet elite destroyed its own system with an absence of an all-consuming conflagration. Pursuing historical hindsight Kotkin points to the importance of the 1973 Arab oil embargo as a watershed event that helped nudge the Soviet system toward economic failure. According to Kotkin the 1973-4 embargo led to the economic collapse of Soviet industry in the late 1970s. For Moscow, the discovery of oil in western Siberia in the 1960s coincided in the 1973 rise in oil prices brought about by the embargo which saved the Soviet economy from disaster. From 1973-1985 oil was responsible for 80% of Soviet hard currency, much of which went for weapons procurement to equalize its relationship to the United States. Further, Russia needed the excess wealth to pay for the war in Afghanistan; assist Eastern European satellites by offsetting energy costs; and importing the necessary technology, pay elites among other expenses. It appeared that Russia was in a period of prosperity, but Kotkin is correct in that it postponed the inevitable collapse of the Soviet system as its industrial infrastructure continued to deteriorate.

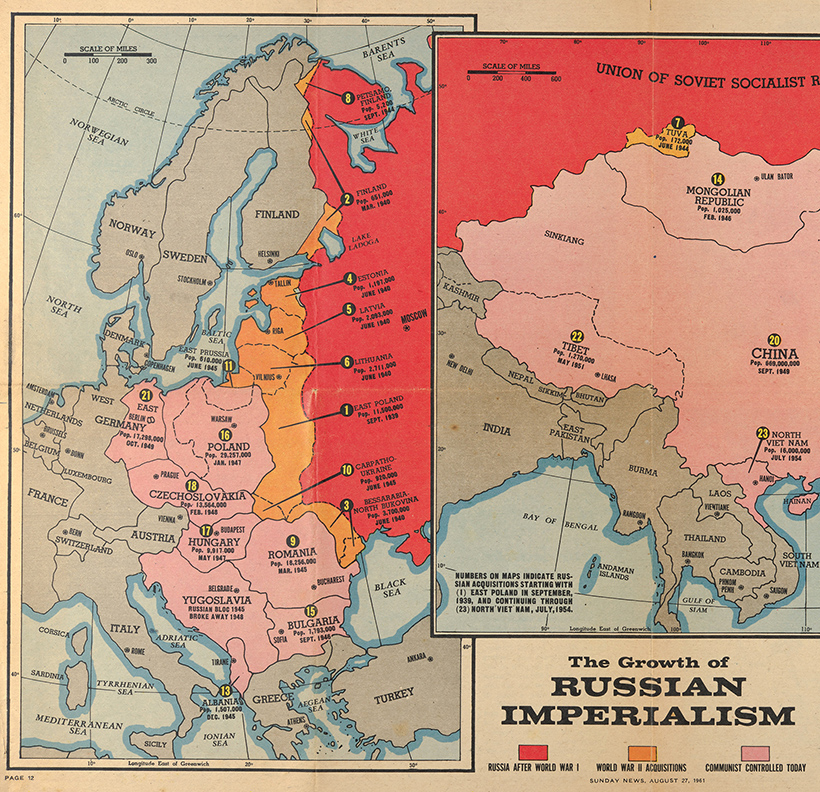

Kotkin’s concise and analytical narrative raises many interesting points among them that the Soviet Union tried to clone satellite regimes after World War II. The problem was that Moscow presented itself as a role model at a time of the post-war capitalist boom in the west. The discrepancies between the two systems were clear and Eastern Europe became a thorn in the side of the Soviets as 1953, 1956, 1968, and 1980 invasions and pressure can attest to. Eastern Europe went from a supposed Soviet strength to a vulnerability as more and more western consumer goods and loans were used to mollify populations. Further aggravating Moscow was the rise of the Chinese Communist Party and Chinese economic expansion and the cost in playing a leading role in the Third World.

It is obvious that Soviet infrastructure was on the decline throughout the 1970s and it could not compete with western capitalism, but what pushed the Soviet system over the edge was the generational leadership shift of the 1980s as the gerontocracy of Brezhnev, Andropov, and Chernenko passed on to be replaced by Mikhail Gorbachev and his ill-fated perestroika. The rot within the Soviet leadership is undeniable and the new Soviet leader sought to save the system from itself as Kotkin argues, “what proved to be the [Communist] Party’s final mobilization, perestroika, was driven not by cold calculation about achieving an orderly retrenchment, but by the pursuit of a romantic dream,” which Gorbachev referred to as “humane socialism.”

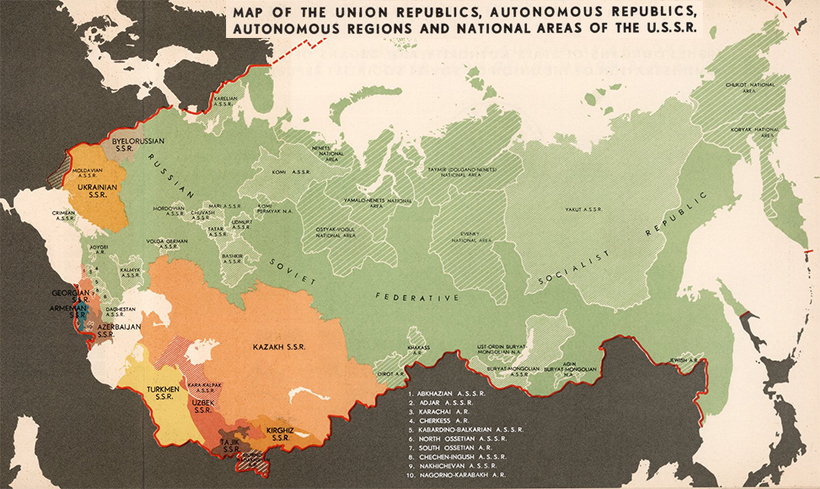

Kotkin raises an important question. Why did Gorbachev’s reform agenda fail so miserably? The author points to a number of reasons that make a great deal of sense. First, Gorbachev’s economic agenda went halfway toward achieving a market transformation, something that was doomed from the start. Second, oil prices declined drastically in 1986 which devastated hard currency earnings curtailing the import of consumer goods and reducing the standard of living for Soviet citizens. Third, by pursuing a halfway approach toward a market economy it fell even further behind the west. Fourth, the disaster at Chernobyl showed the west that Gorbachev was no different than his predecessors, being ensconced in secrecy. Fifth, with Glasnost the public was now aware of secrets buried for decades; murder, the gulag, elite corruption etc. Sixth, 25% of the population was under 25 years of age and were not interested in reforming socialism – Glasnost afforded unprecedented access to “commercial culture and values of capitalism.” Seventh, party officials had no idea how to address a public reconfigured as voters or how to deal with shortages of goods, pollution, deteriorating assembly lines etc. Somehow the Communist Party was supposed to be both the instrument and the object of perestroika. Eighth, later Gorbachev admitted he failed to create a program for the transformation of a unitary state into a federal state and crippled the centralized party machine. Lastly, Russia’s 15 Union republics had clearly defined state borders and their own state institutions and they began to act as independent states which they eventually became.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/yeltsin-speaking-at-press-conference-514704566-5b968f52c9e77c002cf49de3.jpg)

To Gorbachev’s credit he kept the Soviet military out of the loop when it came to events in Eastern Europe and let events evolve. Since the Soviet Union could no longer compete with the west he let the satellite states move on as they and most republics declared their independence.

Kotkin provides an in-depth analysis of the August 1991 putsch and the role of conservative elements, the military, and of course Boris Yeltsin. What he describes has been repeated by many scholars, but what stands out is his analogy of the putsch, its leadership, and its result to George Orwell’s ANIMAL FARM. His presentation is priceless! The result of the dissolution of the Soviet Union did not bring on the onset of American type affluence combined with European style social welfare but a chaotic system by which inflation wiped out the pensions and savings of the Russian people and the squalid appropriation of state functions, property, and wealth by Soviet era elites. In addition to Yeltsin’s cronies and KGB types particularly from Vladimir Putin’s St. Petersburg colleagues and organized crime raping the wealth both monetary and physical from the Russian people.

The 1990s was a disaster and Kotkin fills in the gaps as to what occurred. He carefully explores the machinations of officials, bankers, factory management, political elites, and others who accumulated enormous wealth during the decade. These groups developed numerous schemes from privatizations, auctions, loans for shares, bankruptcy procedures for cut rate hostile takeovers of profitable assets, money laundering, capital flight to offshore accounts leaving nothing for investment as they absconded with the wealth of their country. The bottom line for Kotkin was “How was the incoherent Russian state going to solve the country’s problems when the state was the main problem?”

The main criticisms of Kotkin’s work comes from historian Orlando Figes who writes in the January 20, 2002 ,New York Times Book Review; “This relates to a broader criticism of Kotkin’s work. ”Averting Armageddon” plays down the importance of two vital factors in the Soviet collapse. One is the role of ideology — or more specifically the way in which it lost all meaning to the apparatchiks who deserted Gorbachev in 1989-91. Gorbachev was the last of the believers in the Communist ideal — but his party comrades, for the most part, had long ceased to believe. Their ideology had become little more than an empty slogan, a means of entry to the special shops reserved for the Soviet elite. This fact is essential if we are to understand why so few Communists were prepared to fight for the Soviet regime. The August putsch of 1991 was doomed from the start by the inertia of the middle and the upper ranks of the party. The plotters’ leader, poor old Gennadi I. Yanayev, was aware of this when, his hands in an alcoholic tremble, he read out to the world’s press a declaration of emergency.

The other factor is human agency — or more specifically Gorbachev. He may have started out as a Communist reformer, but there must have been a moment (for he tells us there was one) when he realized the need to dismantle the regime without a violent backlash from the hard-liners. His political maneuverings were intended to avoid a civil war or a crackdown against Eastern Europe that might have led to a disastrous loss of life. He was a sort of political Columbus — setting out with high ideals to find one thing and achieving something better by discarding them. He is a hero of our times.”*

Despite these criticisms Kotkin has written a concise, readable and informative book striking a pleasing balance between tedious detail and sweeping generalizations. He offers a practical, accessible, and informative account of the Soviet Union’s collapse and insights into the impact of Russian history and allows for greater understanding of ongoing events in the Ukraine.

*Orlando Figes. “Who Lost the Soviet Union?” New York Times, January 20, 2002. Figes latest book THE STORY OF RUSSIA was published a few weeks ago.