(Fort Sumter)

Today we are experiencing a country that seems to possess at times an inexplicable dichotomy as people on both sides of the political spectrum rage at each other. Many times, their commentary is not supported by facts and the mention of a “cult” fires the imagination of many. This is not the first time in our history that we have suffered from such a political, social, and economic impasse. If one possesses a modicum of historical knowledge you are aware that in 1814 at the Hartford Convention a secessionist movement had tremendous support in New England. If one moves further ahead in American history we learn about a series of compromises, one in 1820, another in 1850 designed to postpone rather than heal the divergence in American society and culture. Those efforts obviously failed as the events of the 1861-1865 period reflect.

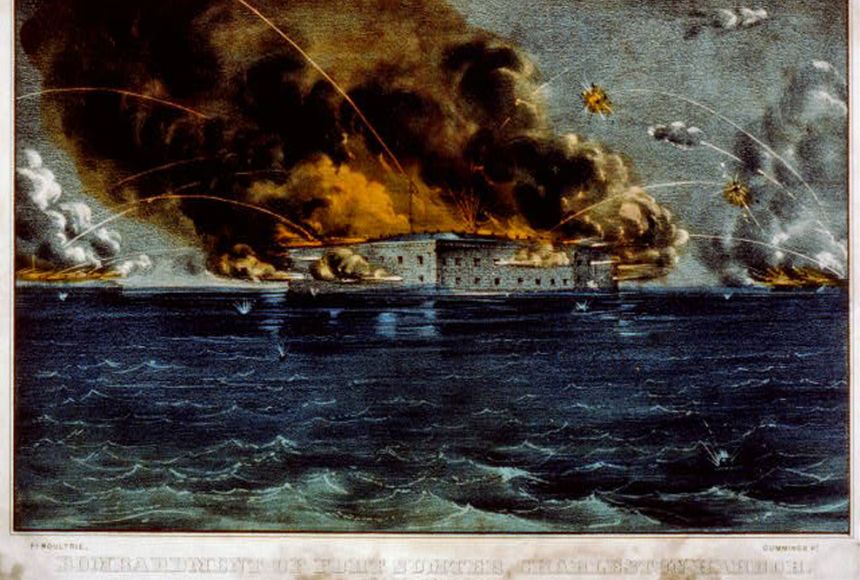

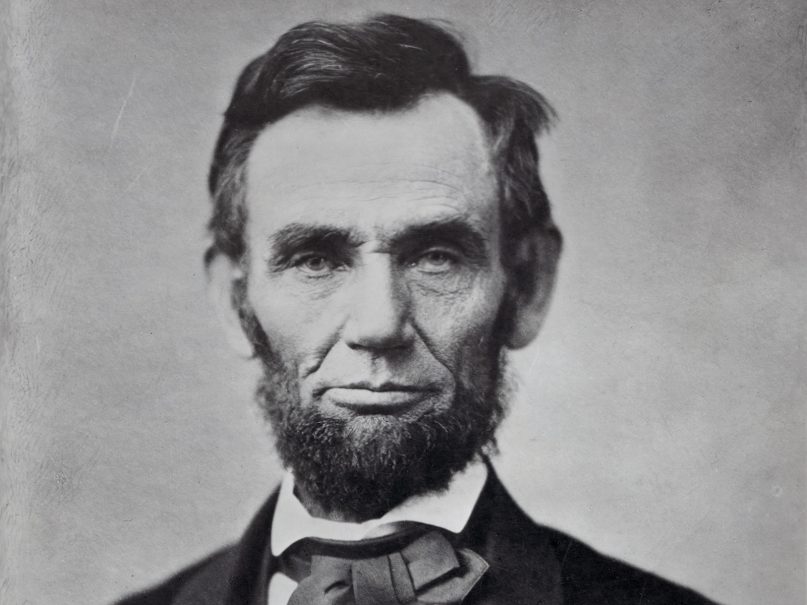

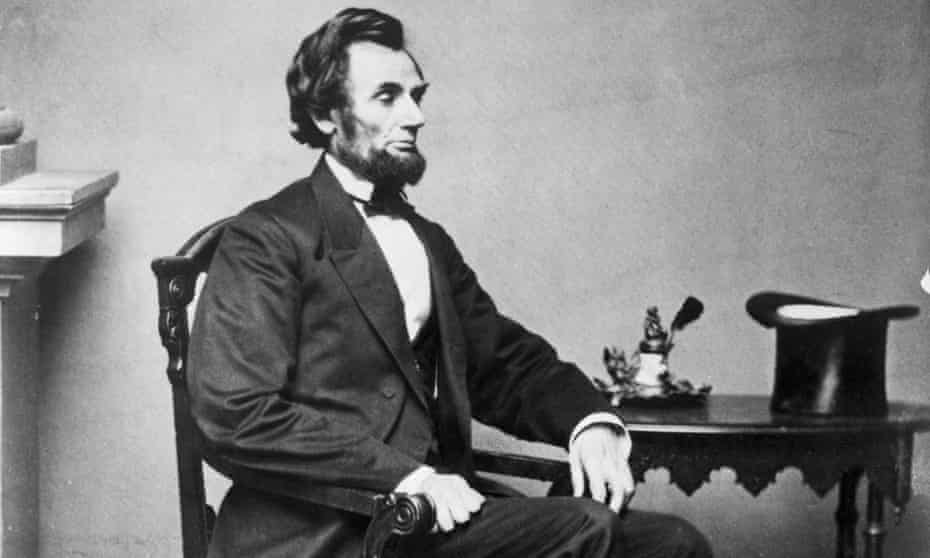

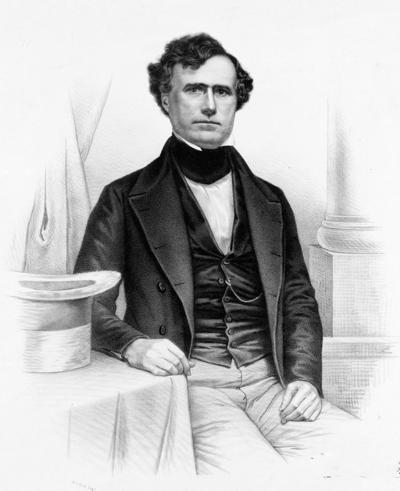

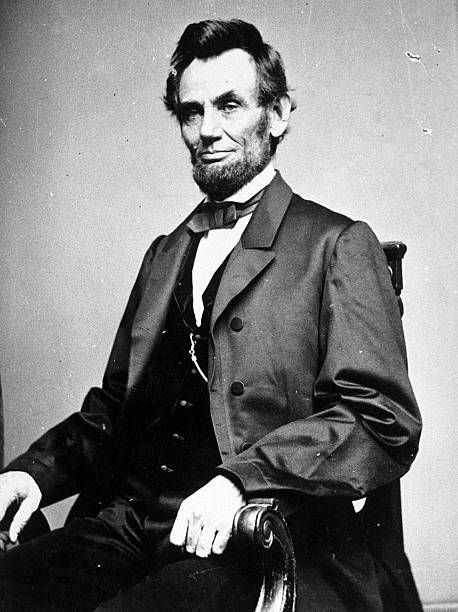

A key to the onset of the Civil War that culminated in 1861 were events taking place following the election of Abraham Lincoln on November 6, 1860, that reached a crescendo when on April 11, 1861, southern militia commander P.G.T. Beauregard demanded that Major Robert Anderson, the commander of Fort Sumter surrender his fort, but Andersen refused. In response Beauregard opened fire on Fort Sumter shortly after 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861. Interestingly, Beauregard had been a student of Anderson. What followed is known to everyone who has ever taken an American history class. There have been countless books written about this period, the latest being Eril Larson’s THE DEMON OF UNREST: A SAGA OF HUBRIS, HEARTBREAK, AND HEROISM AT THE DAWN OF THE CIVIL WAR, a book that focuses on white elites on both sides of the political equation. In so doing his deeply researched monograph focuses on the tragic errors, miscommunication , enlarged egos, remarkable ambitions, tragedies and betrayals that dominated the chief characters that Larsen presents.

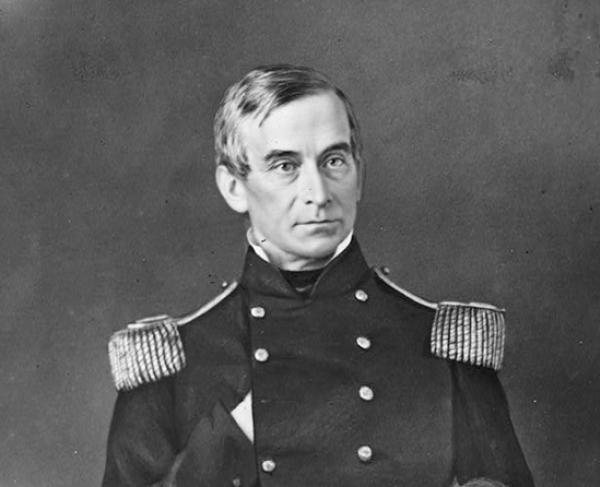

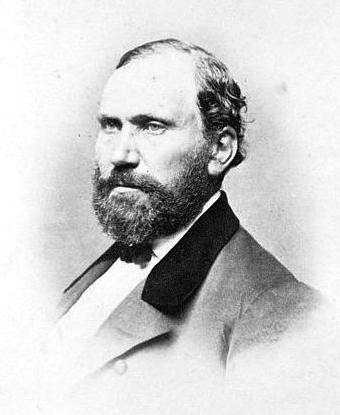

(Major Robert Anderson)

The author is a master storyteller as previous bestsellers – THE SPLENDID AND THE VILE, DEAD WAKE, IN THE GARDEN OF THE BEASTS, THUNDERSTRUCK, THE DEVIL IN THE WHITE CITY, AND ISAAC’S STORMcan attest to. In the past his books have ranged from murder during the Gilded Age, the Galveston hurricane of 1900, crime set in Edwardian London, the voyage of the Lusitania, an American family in Berlin in pre-World War II Germany, the Nazi blitz on London during World War II focusing on the Churchill Family, and now focusing on the events and personalities that led to the American Civil War. As in all of his previous efforts Larsen’s research is impeccable, and his writing maintains the reader’s interest throughout.

Larsen’s main focus is on a few important individuals whose attitudes, wealth, and egos either drove the south toward war, or at the very least secession, and those who tried to no avail to prevent the coming fratricide. Obviously, Abraham Lincoln plays an outsized role. Lincoln was viewed with horror in many parts of the south, especially the home of secession, South Carolina. Most historians, be they Allen C. Guelzo, Michael Burlingame, David Herbert Donald, Doris Kearns Goodwin, and most recently Jon Meachem and Ted Widmer believe that Lincoln’s views pertaining to race, slavery, and the south in general evolved over a period of crises. By 1861 his position was clear – he would not interfere in the south to end slavery, but he would contain it and not allow it to spread outside of the south. Further, he believed in negotiation, not violence to resolve the secession issue, but would not surrender any federal property. Other important northern figures that Larsen explores are William Henry Seward who had a low opinion of Lincoln and believed that he should have been president and that only he had the knowledge and astuteness to end the secession crisis. General Winfield Scott, the Commander of the Army, argued against military action to retain Fort Sumter due to the condition of the northern forces. President James Buchanan who oversaw an administration of incompetence refused to take on the crisis and just let it ride until the next president took office. However, the key player apart from government officials was Major Robert Anderson, the commander of Fort Sumter. Larsen integrates his diaries and other writings into his narrative and provides insights into his loyalties and view of events. For Larsen, Anderson is his most sympathetic character.

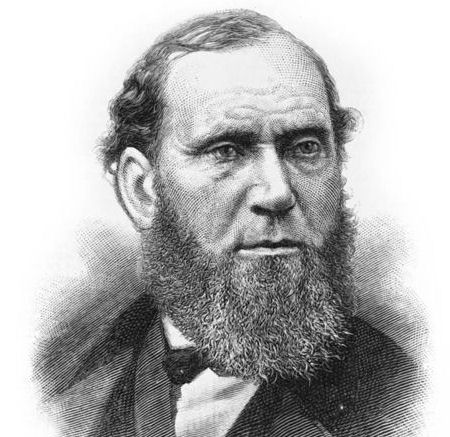

(Edmund Ruffin)

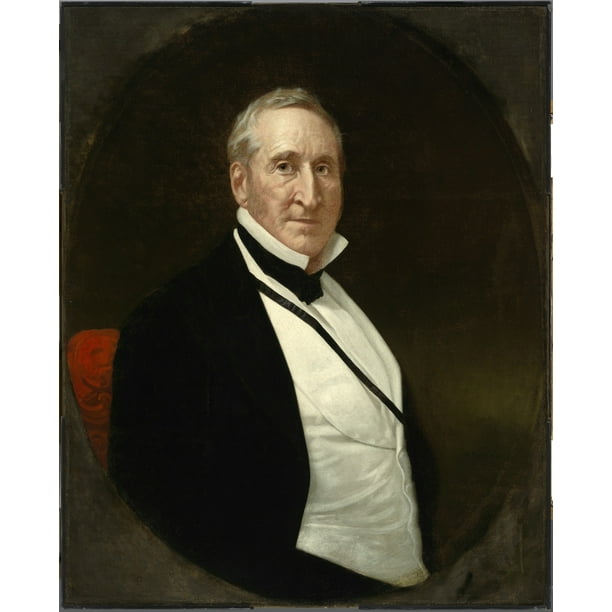

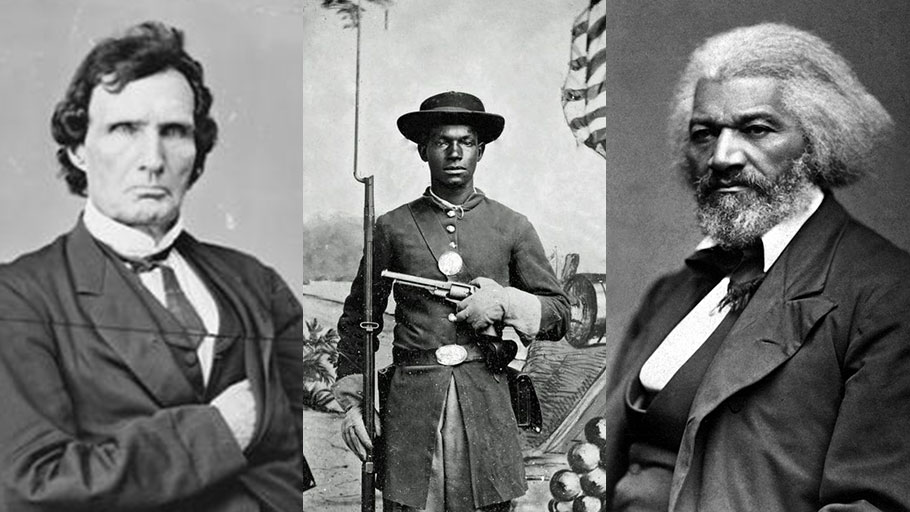

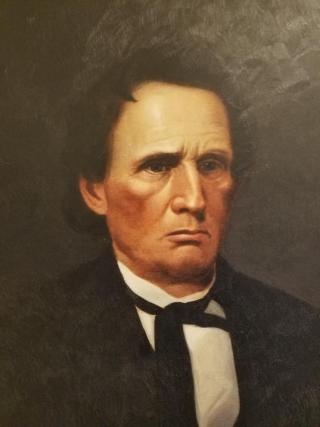

Larsen’s most effective theme revolves around southern “chivalry” and certain genteel behavior that was expected among gentlemen. These gentlemen were southern because northerners did not conform to the south’s view of expected behaviors. Chief among these figures was South Carolina Governor Frances W. Pickens; James Hammond, a South Carolina planter whose racial and economic views pertaining to slavery provided the cornerstone of the southern position. His accomplice was Edmund Ruffin, another planter whose greatest fear was the amalgamation of whites and blacks and what he saw as the eventual emancipation of slavery. For him it would mean the destruction of the southern way of life and utter ruin of everything he stood for. There are other important players that include Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Beauregard that Larsen places under the microscope and concludes that the haughtiness and sense of entitlement by southern planters/politicians make them most responsible for the fiasco that ensued. Larsen describes the palatable arrogance of southern elites after South Carolina succeeded believing they now represented a sovereign nation and should be treated according to their new position with respect and deference.

(James H. Hammond)

Larsen never seems to miss an opportunity to provide details that the reader may never have been aware of. For example, the role of Dorothea Dix whose reputation was elevated by her work with the mentally ill was a firm believer in the ethos put for by Hammond and Ruffin that “negroes are gay, obliging, and anything but miserable.” Her role is enhanced when she reported on a plot to assassinate Lincoln on his way through Baltimore to reach Washington and his inauguration. Larsen delves further into the role of Allan Pinkerton and his undercover spies to protect Lincoln one of which Kate Warne is a major force in Ted Widmer’s recent work, LINCOLN ON THE VERGE: THIRTEEN DAYS TO WASHINGTON. Other important women Larsen incorporates include Mary Chestnut whose diary provides insights into aspects of southern society, beliefs, and politics.

The author’s coverage is extensive, and he focuses on many issues that are components to the larger decision making process. For example, Lincolns relationship with Seward; Lincoln’s communications with his commanders, particularly Anderson and Scott. Further, Larsen discusses attitudes in New York which was seen as an island of pro-confederate sympathy in the north. This was due in large part because New York was home to “bankers, merchants, and shipping companies who maintained close commercial ties with southern planters and routinely issued credit secured by the planters’ holdings of enslaved blacks.” Many New Yorkers argued that the federal government had no authority to block secession. Another fascinating approach that Larsen takes is presenting William Howard Russell, the London Times newspaper correspondent. Russell’s diaries offer careful analysis as he seemed to meet with many prominent figures on both sides and presents a non-American viewpoint.

The key decision that must be made is whether to resupply Fort Sumter after South Carolina demands it be turned over to the state after it seceded. Larsen explains the evolution of Lincoln’s approach which by April 8, 1861,as he decides to provision the fort, but with no weapons and ammunition. The debates, personalities involved take up a quarter of the book and is well thought out and reads like a novel, which is one of Larsen’s strengths.

(Secretary of State William Seward)

According to historian Adam Goodheart; “perhaps no other historian has ever rendered the struggle for Sumter in such authoritative detail as Larson does here. Having picked his way through a vast labyrinth of primary and secondary sources (some of them contradictory), he emerges with a narrative that strides confidently from one chapter to the next. Few historians, too, have done a better job of untangling the web of intrigues and counter-intrigues that helped provoke the eventual attack and surrender — how a few slightly different decisions by leaders on both sides could have led to dramatically different outcomes in the secession crisis, ones that might not have involved a war at all.”*

(Mary Chestnut)

Despite this there are a number of areas that Larsen should address. Why do we need so much personal detail about James Hammond, the flirtations of southern women, especially Mary Chestnut? Where is the face of slavery and blacks in particular? The role of Frederick Douglass and abolitionists in general gets short shrift. However, the strengths of the book greatly outweigh any deficiencies – it is an excellent read and a strong addition to the ever expanding bibliography of the outbreak of the Civil War.

*Adam Goodheart. “Erik Larson vividly captures the struggle for Fort Sumter,” Washington Post, April 26, 2024.

(Fort Sumter)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121121013133tad-lincoln-turkey-pardoning.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/lincoln-tripline-631.jpg)

/Lincoln-Gettysburg-painting-2826-3x2gty-58b999143df78c353cfd0b25.jpg)